I’m grateful to Ruth Wisse for her impressive essay on Abraham Cahan, and for bringing his legacy to a broader audience. Yet, in reading it, I found myself wondering how exactly one could prove her claim that Cahan was “the most [my emphasis] influential Jewish voice in America of the interwar years.” Even if that were the case, the question remains to what extent Cahan’s voice really was that of a visionary, an authority trying to transform the American Jewry for the better? Or rather if it would be better to describe him as an adroit person who had superb meteorological skills for detecting the winds of social change, and—immediately or belatedly—could recalibrate the message sent by him and the Forverts, which under his supreme editorship became a legendary successful Yiddish daily?

In 1901, Lenin explained how he saw the role of the party organ: “A newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and collective agitator, but also a collective organizer.” (Cahan found Lenin pleasant to talk to in 1912, and, in 1920, wrote that no praise could be too high for the Bolshevik leader’s historical deeds.) However, the Forverts, a newspaper of a socialist bent, was not an organ of an American socialist party or any other organization. At its founding, and for a long time thereafter, it followed the example of the German Social Democratic party and its own organ, the similarly titled Vorwärts. Hence the images of Karl Marx, Ferdinand Lassalle, and other European socialist luminaries depicted on the bas-reliefs of its 1912 building. Characteristically, the socialists who worked at the Forverts addressed each other as genose, from the German word for comrade—as opposed the Russian tovarishch or the Yiddish khaver.

The Forverts staff writers and contributors represented a medley of conflicting and shifting understandings of socialism. The veterans among them, including Cahan, were stuck in a no-man’s land between Marxism and the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment that sought to educate and modernize East European Jews. The younger ones were Bundists, Mensheviks, and members of other socialist denominations, sometimes jumping from one to another. Several staff journalists and freelancers spent a stint in the Communist press, including Simon Weber, the Forverts editor from 1970 to 1987.

As for the readers, they too were not of the same mind on many questions. In 1936, when the paper discussed the new Soviet constitution, half of the published letters to the editor scorned democracy and supported a one-party system. In the meantime, the readers and the newspaper turned increasingly conservative, creating an environment in which, ultimately, no place was left even for the great Yiddish novelist Sholem Asch, hitherto the star writer of the Forverts. When Asch did not follow Cahan’s advice to destroy his “Christian” novel The Nazarene and the novel, translated into English, became a bestseller in 1939, the newspaper viciously attacked him and stopped printing his writings.

In a way, Cahan was a “cold Litvak,” a stereotypically rationalist Lithuanian Jew, able to rein in his emotions and do what he felt right. A case in point was his attitude to Sholem Schwartzbard, who in May 1926 assassinated Symon Petliura, the leader of Ukraine during the great wave of devastating pogroms in 1919 and 1920. The Jewish Mensheviks decided to distance themselves from this act of revenge, seeing it as a deleterious manifestation of Jewish nationalism. Cahan admitted in a letter to Raphael Abramovitch, a prominent Menshevik and one of the Forverts’s leading political journalists, that deep in his heart he agreed. Nonetheless, he could not publish Abramovitch’s anti-Schwartzbard article, because it would anger his readership, who hailed the assassin as a hero. In another letter, written in April 1934, Cahan explained to Abramovitch that the Forverts opened its pages only to such debates that “created an atmosphere (shtimung) for our point of view, for our stand.” Significantly, it was our rather than his stand. It is worthwhile to mention that his position of the Forverts editor-in-chief was under an annual contract, and that from time to time he faced serious discontent from the staff.

In September 1925, the Forverts informed its readers about the conference in Philadelphia convened under the aegis of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), with over 1,000 delegates and guests in attendance. By that time, the Immigration Act, signed in May 1924, had all but closed the gates of America to East and Central European Jews, with a preference given to rabbis, scholars, and other intellectuals and professionals. In other words, the era of open immigration had come to an end. This gave particular importance to aid work in other places, which was the JDC’s primary focus.

The key item on the agenda in Philadelphia concerned the allocation of 15 million dollars, which was the target amount for the fundraising campaign aimed to sponsor the creation of Jewish agricultural communities and other projects in the Soviet Union and Palestine. The conference became an hour of glory for the agronomist Joseph Rosen. Following his report, the businessman and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald pledged one million dollars for settlements in the USSR, while the banker Felix M. Warburg, the JDC chairman, pledged a matching donation. The American Jewish press welcomed the adoption of the “harmony resolution”—the compromise decision of sponsoring projects in both the Soviet Union and Palestine.

Cahan did not participate in the conference, but followed the events from afar. Instead he went to Marseilles, the site of a congress of the Labor Socialist International. By that time, some socialist ideologues had changed their attitude to Zionism, finding attractive the idea of “positive colonial policy” in general and the Labor Zionists’ agenda in particular. From Marseilles, Cahan went to Palestine, although previously, in the words of one of his 1921 articles, Zionism “stank through-and-through with dangerous chauvinism.” The 1925 trip brought Cahan to the conclusion that Palestine had “grown in popularity everywhere.”

Where formerly its appeal was to Zionists alone it is now almost universal. It is true that this appeal is to the imagination and sympathies rather than to the sense of concrete possibilities but nevertheless it is widespread and keen. There seems to be a feeling that active and large-scale sympathy might bring encouraging surprises, creating a multitude of unforeseen opportunities and converting the impossible into a living source of hope.

In response, Baruch Charney Vladeck, manager of the Forverts and a prominent figure in the American labor movement (Cahan, who had sharp personal and ideological differences with Vladek, created an excuse to stay away from his funeral in 1938), wrote:

Two movements now terrorize Jewish life: Communism and Zionism; both are ready to sacrifice the Jewish people on the altar of their fanaticism. Let us formulate the question: Palestine also or Palestine only? Cahan has only said, thus far, Palestine also. Let us beware of saying: Palestine only!

Vladeck was willing to entertain the idea that Jewish immigration to the land of Israel might be one of many possible solutions to the growing crisis facing European Jewry, but he could not accept it as the only one.

And indeed, “Palestine only” was not Cahan’s position. In 1927 Cahan spent three months in the Soviet Union and was even impressed by some aspects of Soviet life. At the same time, he did not have any illusions; he understood that the whole Communist system was wrong and that the dictatorship of the proletariat was “as bad as if it were a dictatorship of the aristocracy.” Upon his return to New York, he characterized the Soviet leadership as “a bunch of fanatics,” who were “in a dream, a phantasmagoria,” though—he contended—they, especially such “a sensible man” as Stalin, might “mean well.”

By any measure, then, Cahan was not a prescient political leader. He was a sharp observer rather than a deep thinker. Characteristically, the vast majority of his articles remain untranslated and effectively untouched. No doubt, he enjoyed a following among the readers of the Forverts. At the same time, a lot of Jews disliked him, a man with an abrasive personality and in a lifelong pursuit of idiosyncratic ideological agendas. Let alone that many enthusiasts of Yiddish could not—and some of them still cannot—forgive Cahan his meshugas of declaring his love of Yiddish, especially the “Yiddish Yiddish” of his mother, but fighting against Yiddish education, ridiculing Yiddishists (save the great linguist and leader of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Max Weinreich), and, generally, rejecting the notion of Yiddish culture. Was it an act of Yiddish enthusiasts’ revenge to name a street in the Bronx’s Co-op City neighborhood “Asch Loop,” thus honoring the memory of Sholem Asch rather than of Abraham Cahan? (Vladeck’s name too, it should be noted, is present on the map of Manhattan.) For all that, Cahan left an indelible trace in history as a talented writer and an astute editor.

Unlike many Yiddish writers and Jewish socialists, Cahan was never seduced by Soviet Communism, but neither was he immune to its charms. He did, in time, come around to Zionism, but he could hardly be called an early adopter. He didn’t so much lead left-leaning New York Jews into support for a Jewish state as go alongside them. Yet it would be wrong to say he was a mere panderer, or that he followed the adage, attributed to the French revolutionary Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, “There go the people. I must follow them, for I am their leader.” His greatest skill, however, lay in his ability to figure out which way the people were going.

Could today’s Jewish left produce another Cahan? That depends on which way today’s Jews are headed.

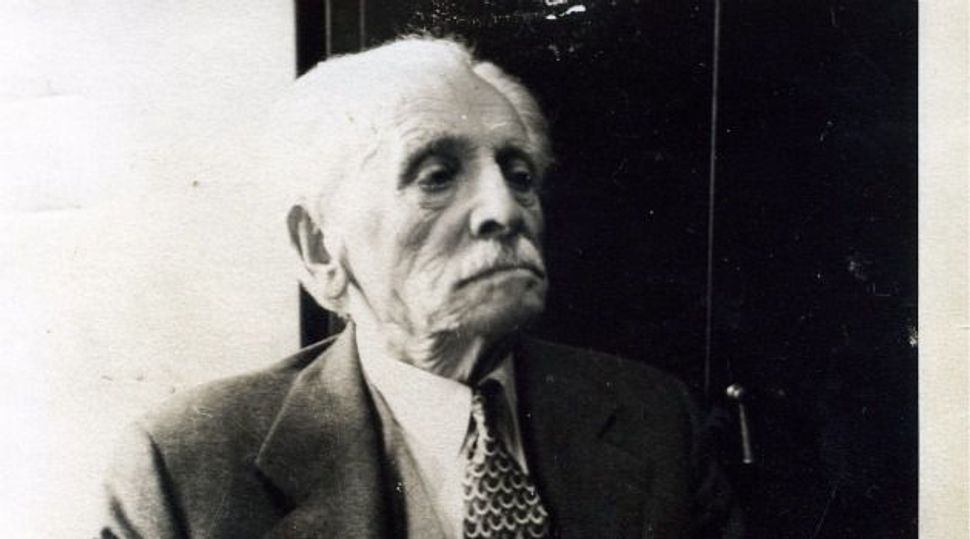

More about: Abraham Cahan, Arts & Culture, Forward