Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem:

A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators.

In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. “How, in what way, where?” urged the transport minister, lapsing into Yiddish: “vi makht men dos?” (“How does one do that?”) Ben-Gurion deflected the query: “That is why we have a security service.”

What the prime minister had deliberately refrained from telling his cabinet was that a combined team from the Mossad and the Shin Bet, Israel’s two most secret services, had located Eichmann in a Buenos Aires suburb where he’d been living under a false identity. Nor did he divulge to them that the agents had grabbed Eichmann off a dark street and kept him in a safehouse for nine days. Or that the team had secreted a sedated Eichmann, disguised as an ill-disposed steward, onto an El Al plane bound for Israel.

In the years following, Israeli authorities worked deftly to keep the spotlight off of Eichmann’s capture altogether and onto his ensuing months-long criminal trial in Jerusalem. Indeed, for more than a decade afterward Israel would persist in keeping the “how” of the capture secret.

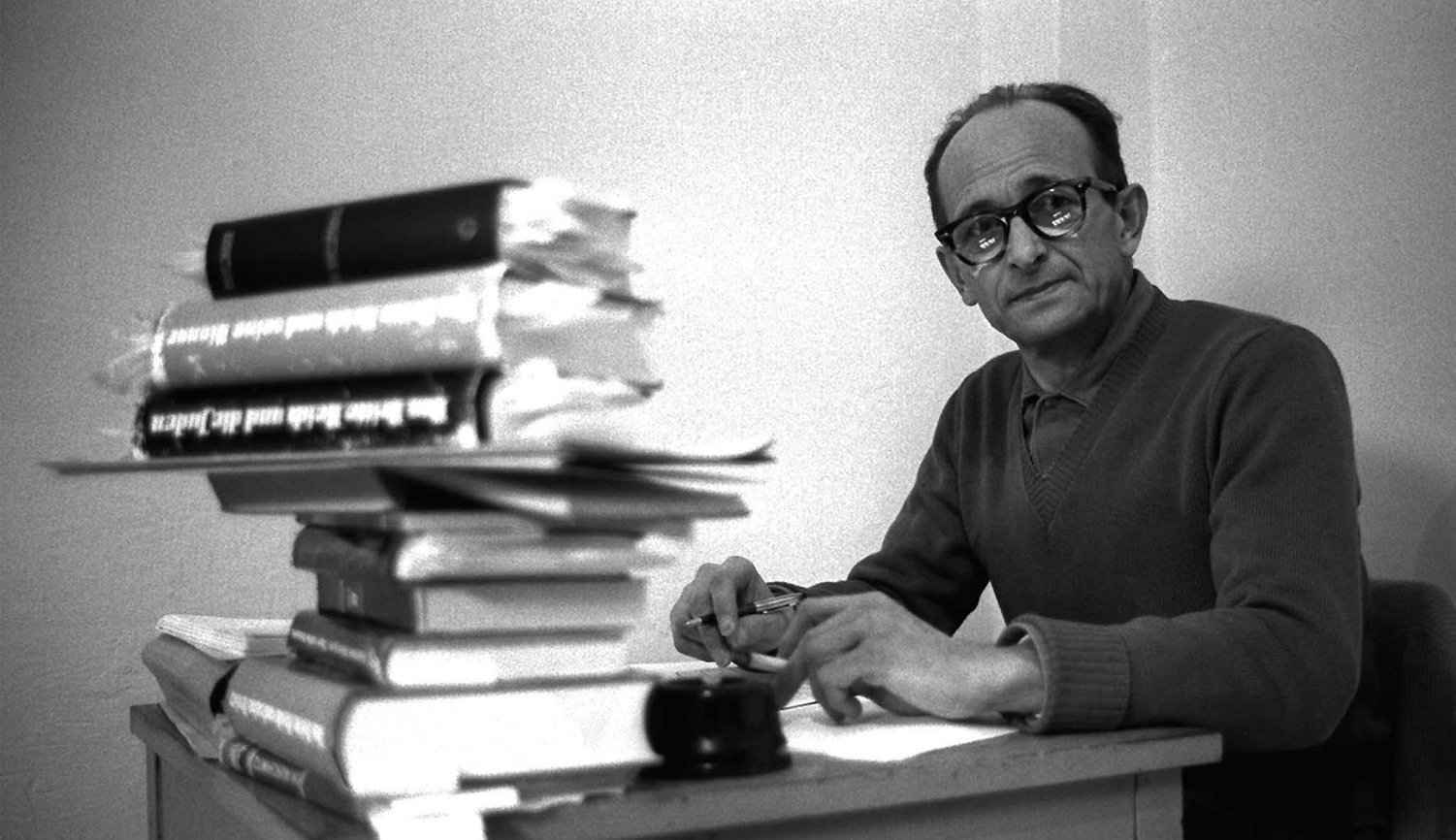

By contrast, the trial proceeded in the glare of television cameras. It was in the courtroom that the world took the measure of Eichmann as he brooded in his glass-enclosed dock. Millions of viewers could gauge his reaction to the testimony of survivors and experts, weigh his own testimony, read the reports of journalists and analysts, and form their opinions.

In America, it was the courtroom reportage of the political philosopher Hannah Arendt that would wield the most lasting influence over the received image of Eichmann. Her dispatches to the New Yorker, collected in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), limned a portrait based almost solely on Eichmann’s conduct in court. Concluding that the accused man displayed an “absence of thinking,” Arendt famously described this “terrifyingly normal” Eichmann as an instance of what she labeled “the banality of evil.”

Today, however, despite its enduring influence in some circles, Arendt’s thesis no longer defines the popular perception of Eichmann. Nor is that perception based any longer on his trial, but rather on the brief period of his initial captivity: the nine days, spent chained to a bed in a safehouse, between his apprehension and his exfiltration from Argentina to Israel. It is this Eichmann, portrayed in popular books and especially in mass-market movies, who is today most familiar to most people.

If anything, these dramatic productions have created an effect even more distorting than Arendt’s idea of the “banality of evil.” During his captivity, we learn, Eichmann revealed human traits he didn’t display in the courtroom. This Eichmann is philosophical, combative, humorous, even seductive. Not only is he thinking; he’s outthinking his captors and interrogators. And far from drab and banal, he is vivid, magnetic, and wholly affable: the very personification of the affability of evil.

It’s tempting to attribute so outlandish a notion to the creative fantasy of one or another director. But no director, dealing with such a sensitive topic, would dare to spin his Eichmann out of wholly imaginary thread. Rather, the cinematic Eichmann can be traced precisely to a single and seemingly authoritative source: the testimony of one of Eichmann’s Israeli captors, a colorful self-promoter named Peter “Zvika” Malkin.

This is a tale best told in parts.

I. False Starts

In the immediate aftermath of Ben-Gurion’s announcement, what fascinated would-be chroniclers of Eichmann’s seizure and captivity was Israel’s sheer derring-do. How did they find the notorious Nazi in the Argentine haystack? How did his captors apprehend and hold him for so long without being exposed? How did they spirit him to the other side of the globe? In short: “How does one do that?”

The first person to appreciate the cinematic potential of the story was Leon Uris, still basking in the afterglow of his 1958 bestseller, Exodus: a fictionalized account of Israel’s creation in 1948, later made into a blockbuster movie by the director Otto Preminger. Uris had a powerful admirer in Israel’s founder and prime minister David Ben-Gurion, who after reading Exodus had written to convey “my sincere thanks and congratulations.” He later granted Uris a personal audience, and sent him an inscribed copy of Exodus bound in olive wood.

When the news of Eichmann’s capture broke, Uris immediately cabled Teddy Kollek, then Ben-Gurion’s chief of staff (later, mayor of Jerusalem), to propose an “exciting motion picture” based closely on Eichmann’s “chase and capture.” The movie would be produced by Columbia Studios within a year, before interest waned. To do it, however, Uris would need official approval as well as “cleared material” gleaned from the agents who’d pulled off the capture. He hoped for all this “in consideration of my past work on behalf of Israel.”

Uris had the right credentials, but Kollek balked. Israel would “seriously consider” the offer, he cabled back, adding, however, that it was “quite unclear if and when [the] inside story can be revealed.” That being the case, any treatment, just as in Exodus, would have to be fictionalized.

Kollek harbored an even larger worry: that a Hollywood-style, cloak-and-dagger treatment of the capture would eclipse the story of the Nazi genocide. Israel, he wrote to Uris, needed a film that would put the Holocaust front and center: “Nazi atrocities” shouldn’t just be mentioned in passing bits of dialogue but should “form the major part of the visuals of the film.” If that would take more time to produce, so be it. Moreover, Kollek warned Uris, it would be hard to grant him exclusive cooperation.

In reply, Uris reassured Kollek that he would be “hitting hard with visual scenes of the Jewish tragedy.” But his studio needed “unqualified assurance” that he would have “exclusive information” about the capture, otherwise “I must automatically withdraw my interest.” It was almost an ultimatum, but in the end Uris backed out for another reason: his studio didn’t want to advance any money upfront, and he couldn’t find another to back him.

If the famed Uris had written the screen play of an Eichmann movie, would it have had the impact of Exodus, the film? We’ll never know, but Uris’s correspondence with Kollek raised an issue that would plague all subsequent attempts to dramatize the Eichmann capture: the issue, in a nutshell, that there was no way to compress and integrate the immense Holocaust story into a few days of “chase and capture” in Argentina.

Nor was that the only problem. Uris wanted to write the “inside story,” but the “inside story” still remained classified. Kollek did disclose that it was “a terrific adventure story and rather better than the normal gangster cops-and-robbers type.” But Israel’s official position was, and would remain, that Eichmann had been captured not by state agents (as we’ve seen) but by “volunteers” who had turned him over to the Israeli government.

That’s because the operation had dented Argentine sovereignty, and Argentina had taken its grievance to the UN Security Council. There ensued a nasty diplomatic brush-up, which left Israel isolated and Argentina’s Jews feeling deeply vulnerable. So the fiction had to be maintained, and it became a habit, even after Israel apologized to Argentina. For years afterward, those who planned and carried out the operation were forbidden to mention their involvement.

Not that the nine days of Eichmann’s captivity were entirely blacked out. In anticipation of his trial, the Israeli government did “seed” publication of a highly censored version. Ben-Gurion entrusted Moshe “Moish” Perlman, the newly-retired head of the state’s information service, to write a quick book on the capture. Ben-Gurion thoroughly vetted the finished manuscript, as did Isser Harel, then the head of both the Mossad and the Shin Bet and the operation’s mastermind.

The book, appearing on the eve of the trial as The Capture of Adolf Eichmann (1961), toed the official line. There was no mention of Israel’s government, its secret services, or El Al. The “volunteers” were “youthful pioneers” who had created “a cooperative farm village in a desert outpost in southern Israel” and had somehow deposited Eichmann on Israel’s shores.

Pearlman complained to Kollek that censorship had rendered the book “less interesting” than it might have been. (On another occasion he used more pungent adjectives: “emasculated, bowdlerized, thoroughly expurgated.”) Hannah Arendt agreed: “The story told by Mr. Pearlman was considerably less exciting than the various rumors upon which previous tales had been based.” True, but the reason wasn’t just censorship. For Pearlman genuinely had almost nothing to report about Eichmann’s own conduct in captivity. Except for some brief interrogations, he wrote, “there was no further conversation between Eichmann and his captors. He was guarded in silence. It was boring. . . . The hours dragged with a heavy, sluggish languor.”

Here, then, was the practical problem with any attempt to dramatize the story between the capture and the flight out. During Eichmann’s Argentine captivity, he remained blindfolded and cuffed to his bed while members of the Israeli team took turns watching over him. Yes, there was tension in the air because of fears that something could go wrong. Yes, there were logistical challenges. But the agents weren’t working against an opposing intelligence service, or behind enemy lines. Rafi Eitan, a team member who planned and executed this and many other field operations, would later classify the capture of Eichmann as “one of the simpler operations that I did.”

On top of that, his guards weren’t supposed to speak to him. Although Eichmann did say a few things to the Shin Bet operative whose task was to question him (and whom we’ll meet later on), the officially determined aims of the interrogation were highly limited: to identify Eichmann beyond doubt; to ferret out how his family might react to his having gone missing; and perhaps, if Eichmann knew the whereabouts of any other Nazi war criminals, to bag one. (He didn’t.) There was also an instruction from Israel’s attorney general: persuade Eichmann to sign a statement agreeing to stand trial in Israel. This he finally did; otherwise, the nine days passed in tedium.

All of this explains the failure of what would become the capture’s first fact-based cinematic treatment. In 1965, Isser Harel, who oversaw the operation, wrote an account of it for internal use, relying on classified documents to do so. Later, in retirement, he sought to publish his manuscript. After a hard-fought legal battle with the state, the book finally appeared in 1975 under the title The House on Garibaldi Street. (Eichmann’s house in Buenos Aires was located on a street by that name.)

Harel’s book, within certain limits, confirmed what everyone already assumed about how the operation was born, who carried it out, and how the capture itself was coordinated: the aspects to which Harel had made his own crucial contribution. He’d spent little time in the safehouse, however, and almost none with Eichmann. Yet tales of his Mossad tradecraft made the book into a best-seller in many languages, and established Harel as the Israeli most responsible for the operation.

In an attempt to dramatize the book, The House on Garibaldi Street was made into a television movie of the same title in 1979, with Martin Balsam in the starring role of Harel. It fell flat. As People magazine put it at the time, the capture had somehow been rendered “as suspenseful as the writing of a parking ticket.” To the Washington Post’s critic, the filmmakers, in resisting “the temptation to sensationalize the material,” had “de-sensationalized it into a state of torpor.” The New York Times reviewer pronounced the result “almost irritatingly limp.”

No wonder. In Harel’s book-length celebration of himself and the Mossad, Eichmann figured as little more than a stage prop, and the film remained faithful to the book—if not also, ironically enough, to a variant of the Arendtian view. When the Israeli team first captured Eichmann, Harel wrote, “they believed they had to contend with a satanic brain, a brain capable of springing a daring surprise on them.” But not for long:

At the beginning of his captivity Eichmann quaked every time anything unusual happened. When he was told to stand up he shook like a leaf. The first time they led him into the patio for his daily exercise he was in a state of abject terror, apparently believing they were taking him outside to kill him. . . . He behaved like a scared, submissive slave whose one aim was to please his new masters.

“It wasn’t easy,” wrote Harel, “for the men to reconcile the actuality of this wretched prisoner with their image of the superman who wielded the baton in the annihilation of millions of Jews.”

The missing ingredient was obvious, and it wasn’t the lack of suspense: after all, who in a theater audience wouldn’t know that the story ended with Eichmann smuggled out of Argentina to Israel? To make a film compelling, a human drama was needed. Yet if the captive was so scared, submissive, and wretched—so limp, so banal—how could a dramatic dialogue be fashioned around him?

II. Eichmann Speaks!

Despite the TV movie’s failure, Harel’s breakthrough revelations opened the gates to competitors. If Harel could publish (and profit from) an account of the once-secret operation, how could other team members be denied their moment in the limelight?

Enter Peter “Zvika” Malkin, a hulk of a Shin Bet agent whose assignment had been to grab Eichmann and subdue him at the moment of capture. Born in Poland in 1927, raised in the tough alleys of Haifa port, Malkin was the type of agent of whom every espionage organization needs at least one: a street-smart muscle man, fast-thinking, smooth-talking, and deceptive. In addition to his physical prowess, he was good at disguise and picking locks. He also knew explosives and had served as an all-around sapper in Israel’s war of independence.

During the mission in Argentina, it was Malkin who (with some help) stuffed Eichmann into the getaway car, thus insuring his renown as the Jew who first laid hands on the Nazi mass-murderer. His quarter-century-plus career in Israel’s secret services—in later years he moved over to the Mossad—would include tracking German rocket scientists in Egypt, uncovering Soviet spies in Israel, and other exploits shrouded in secrecy. He twice received Israel’s top security prize.

After retiring from the service in 1976, Malkin made a lunge for fame, leading a private operation to capture Josef Mengele, the notorious SS doctor at Auschwitz known as the “Angel of Death.” Nothing came of it: Mengele had already drowned a few years earlier in Brazil. By then Malkin was living mostly in a studio apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where he ran a “security and anti-terrorism” consultancy. Eventually becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen, he seemed destined to fade away: one more castaway veteran of Israel’s clandestine wars.

Instead, to his lasting celebrity, Malkin totally rewrote the script of Eichmann’s capture. In 1983, riding on Harel’s precedent, he published (with the Israeli journalist Uri Dan) his own Hebrew account of the operation. There he used a pseudonym (“Peter Mann”), but in 1986 he stepped out of the shadows when the Jewish Museum in Manhattan mounted an exhibition to mark the 25th anniversary of Eichmann’s trial. Malkin spoke at the opening, and his appearance led to a page-two photograph and interview in the New York Times under the dramatic headline: “Man Who Seized Eichmann Recalls Secret Role.” He was on his way.

In 1990, Malkin (with the American journalist Harry Stein) published Eichmann in My Hands: a combination of autobiography and spy thriller. In the book, and in interviews, he offered an astounding revelation: on his shift during those long nights in the safehouse, he had defied orders and secretly engaged in deep heart-to-heart talks with the captive. The book reports these conversations in detail, some of them purportedly verbatim despite the intervening passage of three decades.

Indeed, this “lengthy dialogue with his captive,” as the Times described it, was the book’s centerpiece. Not only did it claim to open a window into Eichmann’s true mind, but Malkin also claimed it was he who persuaded Eichmann to agree in writing to a trial in Israel, something “his” captive had initially been very reluctant to do.

Here was the emotional depth that the story had always lacked. Kirkus Reviews, the influential pre-publication arbiter of critical opinion, hailed Malkin’s book as “a masterful combination of gripping drama and compelling moral issues.” Dramatization soon followed. In 1996, the book was made into a television movie, The Man Who Captured Eichmann, starring Arliss Howard as Malkin and Robert Duvall as Eichmann. Saluted by the Times as “a tight psychological drama,” it was lauded in the Los Angeles Times as a vast improvement over the “slow pulse” and “monotone” of The House on Garibaldi Street—a quality attributable precisely to its representation of Eichmann “largely through the prism of Malkin.”

The book and television film (for which Malkin served as a consultant) made him the go-to “man who captured Eichmann.” The leather gloves he’d worn in laying hands on the fugitive were cast in bronze and offered for sale in a limited edition. In 2002, drawings he’d made during his shifts watching the prisoner were published, and some were exhibited at the Israel Museum, in various Jewish community centers and galleries in the United States, and at the Wannsee House in Berlin where in 1942 Eichmann had attended the Nazi planning conference for the “final solution.” Testimonials, assembled on his website, described him as charming, dramatic, humorous, memorable, spellbinding, warm, and witty. (For a sample, watch Malkin tell his version here.)

At one point, he even created the Peter Z. Malkin Foundation, whose declared purpose was to enable him “to lecture monthly to youth and adults throughout the world without charge.” In these appearances he needed little prompting. A visit by Malkin to the Forward newspaper began with a brief question posed by a staff member, to which (as the paper’s then-editor Seth Lipsky would recall) he responded by “talk[ing] for two hours and 45 minutes before anyone could get in the next question.”

Malkin’s death in 2005 at the age of seventy-seven elicited reverential obituaries in the leading American and British newspapers; the New York Times Magazine even ran a posthumous profile—really a synopsis of his book—in its end-of-year issue for 2005. He ended his life as a much-sung hero, far eclipsing Isser Harel. American Jews, in particular, admired him greatly.

Why? What made Eichmann’s “lengthy dialogue” with Malkin so compelling, especially to Jews? Initially, it was simply the stark pairing of these two men. Although Malkin, who arrived in Haifa before the war, wasn’t himself a Holocaust survivor, he had lost a sister and her children who stayed behind. He thus combined in one person the Jewish victim and the Israeli avenger. Alone in the room with Eichmann, he became not just an interrogator or prosecutor but “every Jew.” In addition, the fact that the guards were forbidden to talk to the prisoner infused their colloquies with a heady aroma of the surreptitious and the prohibited—this, despite the fact that by the time the book came out, much of the actual substance wasn’t really new.

As Malkin tells it, in their talks Eichmann rehearsed a number of the points he would subsequently raise in his interrogation and again in his trial. Such as: he was an obedient soldier only following orders; he organized only the transport of Jews, not their extermination; and he had nothing against the Jews per se. (“I was never an anti-Semite,” he told Malkin. “I have always been fond of Jews.”)

But Eichmann, Malkin discovered, had “a sharp mind.” Though “sometimes frankly obsequious . . . he was also canny. He knew exactly what he was doing.” In their to-and-fro, Eichmann defended himself “with a cool aplomb. . . . Listening, it was not quite so easy as I had supposed it would be to frame cogent replies.” Theirs was a secret battle of wits, between captor and captive, Jew and Nazi, whose forbidden conversations turned them into “co-conspirators.”

Two aspects of their safehouse dialogue markedly diverged from what would later be heard in the trial, thus rendering them all the more titillating. The first consisted of moments in which Eichmann expressed loving concern for his family, especially his youngest boy; he suspected they, too, might be targeted, and his fears gave rise to “paroxysms of anguish and desperation.” The second, by contrast, arose in outbursts that suddenly exposed the hatred of Jews embedded within him. Both of these qualities enhanced Malkin’s image of him as someone profoundly evil yet at the same time all too human.

Their most famous exchange bundled all of these elements together:

“My sister’s boy, my favorite playmate [said Malkin to Eichmann], he was just your son’s age. Also blond and blue-eyed, just like your son. And you killed him.”

Genuinely perplexed by the observation, he actually waited a moment to see if I would clarify it. “Yes,” he said finally, “but he was Jewish, wasn’t he?”

In a culminating passage, the dialogue achieves its practical outcome: Eichmann’s signing of the agreement to stand trial in Israel. This, according to Malkin, he alone was able to secure by giving Eichmann small, illicit privileges (wine, cigarettes, music on a record player) and by winning his trust.

III. Eichmann Becomes Kingsley

If, thanks to its dramatic power, Peter Malkin’s narrative of the capture displaced Harel’s, even he could not have imagined the extremes to which his version of events would lead after his death.

In 2018, MGM released Operation Finale, the biggest production of the capture story ever made. Its director, Chris Weitz, said he was influenced “more by Peter Malkin’s memoir” than by any other book on the subject. True, Weitz also claimed that the film was based on a “bunch of primary sources.” But in fact the MGM production drew extensively on Malkin’s book, and exclusively so for Malkin’s conversations with Eichmann, for which there is no other source.

Weitz then made a decision that carried Malkin’s narrative into a higher realm. In Malkin’s book and its TV movie derivative, Eichmann still bore a residual resemblance to the “wretched” figure recalled by the Israeli team members. But when Weitz cast the revered Sir Ben Kingsley as Eichmann, that wretched figure went out the window.

As Weitz himself noted, Kingsley brought “a tremendous amount of pathos and charisma” to the character of Eichmann. Reviewers agreed. The New York Times critic wrote admiringly that Kingsley as Eichmann “is capable of suppressing neither his natural charisma nor the impish aspects of it.” Time Out lauded Kingsley for delivering “a complex and masterful performance, generating more empathy for a Nazi than you might expect.” Eichmann, remembered by Harel as “submissive,” was now portrayed as if “he’s related to Hannibal Lecter,” wrote one reviewer, “all diabolical cunning and four-dimensional chess.”

An Israeli reviewer watching a screening for a Jewish audience in New York described the effect on the theatergoers produced by Kingsley’s at once “cunning but not raging, cynical and not ideological, fragile and non-threatening” Eichmann:

The audience seemed to fall under Eichmann’s spell. Viewers found themselves uncomfortably shifting as Eichmann emerged in front of their eyes at the pinnacle of his human glory. Smart, knowledgeable, sensitive, and scared. And, worst of all, with a sense of humor.

This Eichmann—Malkin’s Eichmann, amplified by Weitz and Kingsley—quickly became enshrined as the Eichmann for American Jews. Four hallowed Jewish venues—the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, the 92nd Street Y in New York, the JCC in Manhattan, and the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles—hosted special pre-release screenings followed by on-stage discussions with Weitz, Kingsley, and other actors. While, in the general media, reviews of the film were mixed, most Jewish reviewers gave it an enthusiastic thumbs-up. One did venture that he detected some “emotional heartburn” in a New York Jewish audience, but nothing more.

Why the swooning? Part of it was Kingsley: if he played Eichmann this way, certainly it must be “good for the Jews.” After all, he’d been cast in the past as Anne Frank’s father Otto, as Simon Wiesenthal, as Itzhak Stern (in Schindler’s List), and as Moses. And all through the film shoot, so Kingsley announced, he had carried a photograph of Elie Wiesel in his pocket. “Elie, I’m doing this for you,” he’d said to himself each day on the set.

Another part of it was that Operation Finale included those “flashbacks” to the Holocaust that had been the stumbling block to Leon Uris. Only the previous spring, a poll revealed that two-thirds of American millennials had no idea what Auschwitz was. Few of them would ever set foot in the Holocaust Museum in Washington. And now, unimpeachably portrayed, the Holocaust had come to them.

If so, what did it matter if the movie, “based on the incredible true story,” may not have gotten Eichmann just right? Hollywood movies are deliberately designed to entertain, and only then (occasionally) to educate. They operate by their own tried and commercially tested rules. So shouldn’t Jews be grateful when any big studio embeds flashbacks of the Final Solution in a chase movie meant to appeal to younger audiences?

Still another part of it was the way the movie cleverly confirmed both sides of the argument over Arendt’s banality-of-evil thesis. Did Harvard’s Alan Dershowitz get it right in declaring that “Kingsley’s fictional portrayal of Eichmann, not as banal but as brilliantly evil, is far more realistic than the allegedly nonfiction account by Arendt”? Or did David Sims in the Atlantic get it right in asserting that “Weitz’s film never explicitly echoes Arendt’s phrase, but the movie’s portrait of Eichmann, played with undeniable charm by Ben Kingsley, is suffused with it”? Although they saw the same movie, one was sure it refuted Arendt’s thesis, the other that it confirmed it.

Weitz and Kingsley obviously counted on the film’s exciting of Jewish interest. But since both also feared that casting Sir Ben as Eichmann might pose a problem, they worked hard in advance to frame any potentially negative fallout as benighted. Their message: it was legitimate to show Eichmann’s human side, because he was human.

“The tragedy is that the Nazis were human beings,” Kingsley said. “And I think to demonize them, to play them as a B-movie villain, to play them as some Marvel comic baddie would do a terrible injustice to the history and to the victims of the Holocaust.” “Ben and I,” said Weitz, “were both intent that Eichmann be portrayed as a human being. Not in order to garner people’s sympathy for him, but to indicate that this kind of crime is committed not just by demagogues and sociopaths.”

All of this neatly evaded the point. It wasn’t that Kingsley “humanized” Eichmann. No one doubted that Eichmann had a range of human emotions, that he loved his wife and children, or that he enjoyed small pleasures. The point, once again, was, and is, that Weitz and Kingsley portray him as empathetic, clever, affable, and, yes, “impish.” Their Eichmann isn’t just human; this captive is captivating. His Israeli captors, wrote one reviewer, “pale in comparison to him.”

None of this bore any resemblance to Eichmann during his Argentine captivity, according to the other witnesses. He struck Harel as a “miserable runt, who had lost every vestige of his former superiority and arrogance the moment he was stripped of his uniform.” He was a “nonentity, devoid of human dignity and pride.” Rafi Eitan (who many years later would gain notoriety as the “handler” of Jonathan Pollard) was even blunter. “I wanted to understand Eichmann’s character, his capability,” he said. And what did he discover? A “very, very mediocre person.” Eitan added, ironically, “What’s frightening is that any person with only a mediocre-plus capacity for getting things done—and I don’t think he had more than that—could achieve what he did . . . could end up doing what he did.”

Of course the Eichmann of 1960, captured, blindfolded, and chained to a bed, was no longer the Eichmann of 1942: the determined, relentless, and demonically successful pursuer of Jews. That Eichmann was not to be underestimated. But Eitan, like Harel, reported what he saw. Which means that the Eichmann of Operation Finale was definitely not the Eichmann of those nine days in the safehouse. The person recalled by Malkin, amplified by Weitz, and magnified by Kingsley, was another man altogether.

IV. Not in Israel

On the face of it, this Hollywood version of Eichmann should have excited much interest in Israel. Aside from Eichmann himself, virtually all of the characters are the Israeli members of the capture team. Even Ben-Gurion makes an appearance. The film also features a well-known Israeli actor, Lior Raz (star of the Netflix thriller series Fauda) in the role of Harel.

But it didn’t happen. Shortly after its American premiere, Operation Finale was announced in Israel as “coming soon to theaters.” Promotional materials and a Hebrew-language poster circulated, but that was all. The movie never had a pre-release test with an audience in Israel (as it had in New York and London), and it wasn’t even submitted to the Israeli film rating board. Instead, Operation Finale went straight to Netflix—a decision that raised eyebrows since the lack of a theater run consigned it to critical obscurity.

How was it that a movie applauded at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, and lauded by American Jewish reviewers, didn’t even play in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv? What was it about Operation Finale that negated its Israeli launch?

It was Kingsley’s portrayal of Eichmann. The Israeli actor Raz predicted as much in his remarks at the Holocaust Museum in Washington:

When we see Eichmann in the movie, and you see the tenderness that Sir Ben [Kingsley] has in his personality, and you see it on the screen, I believe that to Israelis, it will be a little bit hard to see that, because you feel for him for a second, for a minute, and for Israelis I know it is going to be hard to see it.

Yes, “feeling” for Eichmann and appreciating his “tenderness” would have been “hard” for most Israelis. Raz’s implied message to his audience at America’s shrine to the Holocaust, however, was that his countrymen lacked the deeper insight afforded by “art.” After the film went to Netflix in Israel, Weitz, echoing the sentiment and oozing condescension, recapitulated his own basic message.

“The reaction has been interesting,” Weitz said about the Israeli response, “really mixed. A strong note I got [is] that a lot of people are thrown by the portrayal of Eichmann as a human being.” Israelis, who saw Eichmann as a “really sort of demonic figure,” had trouble “grasp[ing] the fact that he was also a human being.” But, he added, that was exactly why he and Kingsley had decided to portray him that way—in order to “put more pressure on our sense of ethics rather than excusing us by identifying these evildoers as just the ‘other.’”

As we have seen, it was Eichmann’s Israeli captors who pegged him for the mere human he was. Harel’s book, depicting Eichmann as trembling and submissive, was read by almost every Israeli of an earlier generation. By contrast, it was Weitz who turned Eichmann into that supposedly rarer human, affably evil, capable of disputation and defiance even while chained to a bed, facing death. “Eichmann Never Looked So Good,” ran the headline of the only major Hebrew review, on the Israeli website Ynet: “The film depicts Eichmann in the familiar cinematic role of evil linked to intellectual sparkle and humor. . . . Weitz and [the screenwriter Matthew] Orton turn a despicable character into an evil attraction.”

In short, Kingsley had ended up playing precisely the “B-movie villain” he said he didn’t want to play. Had the film opened in Israeli theaters, it’s likely such notices would have proliferated. In Israel, closer to the Holocaust, farther from Hollywood, still stubbornly resistant to “artistic” manipulations of the Final Solution for present purposes, history prevailed over celebrity.

V. It Never Happened?

So far, we’ve seen how, to Eichmann’s posthumous benefit, Malkin’s version has definitively displaced Harel’s, at least in America. Now, in light of the Israeli response, I want to ask whether still another version deserves definitively to displace both Malkin’s and Malkin’s Hollywood avatars. That is the version of another member of the capture team: Zvi Aharoni.

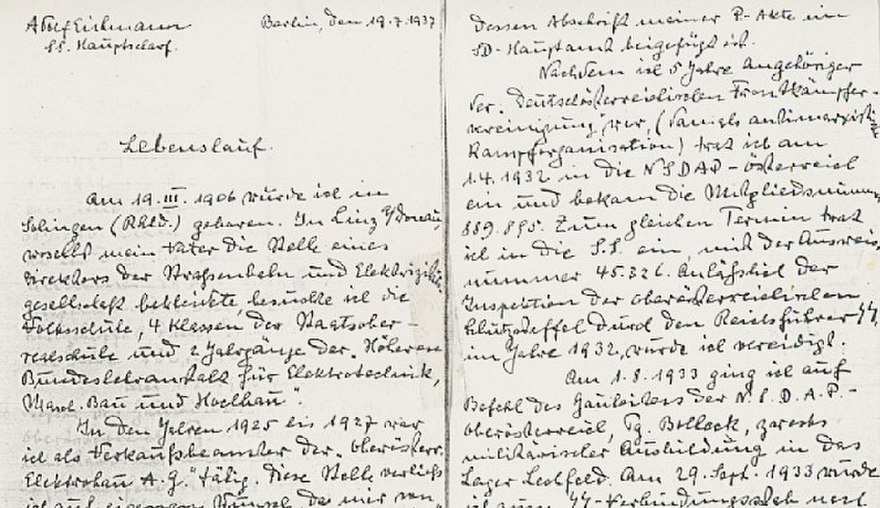

Born in Frankfurt (Oder) in 1921, Aharoni fled Nazi persecution as a teen and arrived in Palestine in 1938. During World War II, he joined the British army. Since he spoke native German, he was made an interrogator of captured German officers in Egypt, North Africa, and Italy.

Aharoni fought in Israel’s war of independence as a company commander and afterward joined the Shin Bet, where he gained renown for his skills as an investigator and interrogator. In 1958 he traveled to Chicago to study the latest techniques in interrogation at a famous American lab. Returning home, he brought back with him Israel’s first polygraph machine, a gift from the chief of CIA counterintelligence, James Angleton.

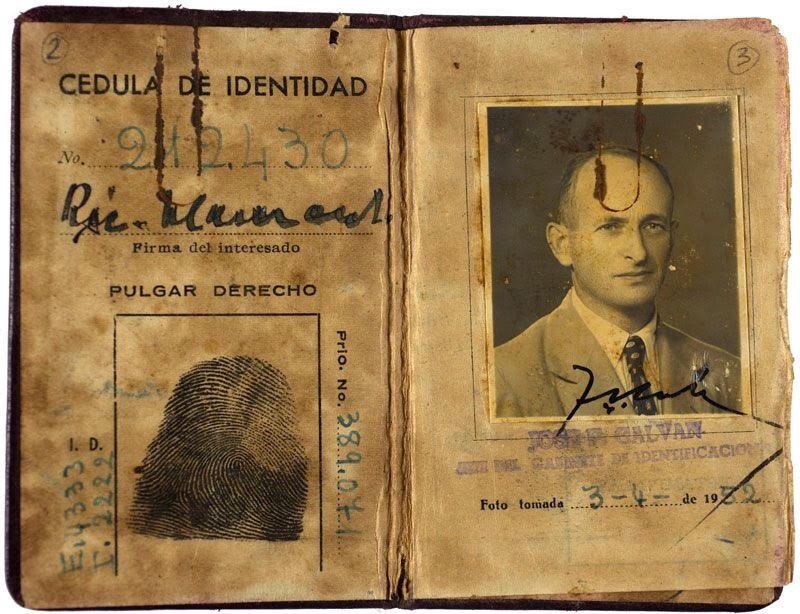

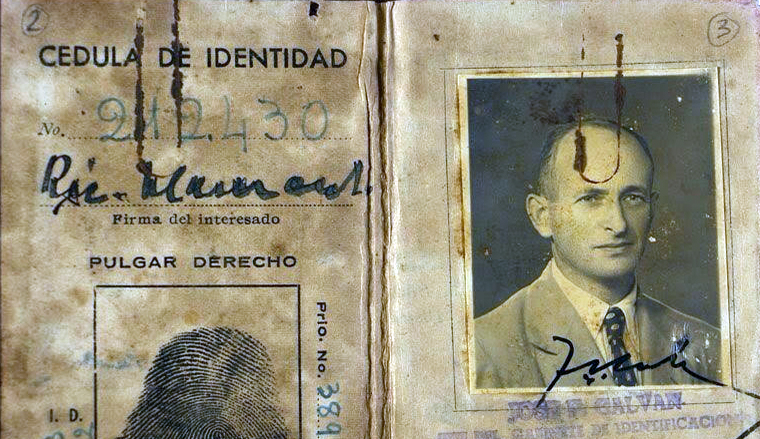

When credible reports of Eichmann’s whereabouts reached Israel, it was Aharoni whom Isser Harel dispatched to Buenos Aires to make a positive identification. Aharoni got a fix on Eichmann’s house, placed him and his family under surveillance, and even secured close-up photographs of the fugitive. He also established Eichmann’s daily routine, at one point sitting directly behind him on a commuter bus. Aharoni participated in the capture as the driver of the prime getaway car. Once in the safehouse, he got Eichmann to admit his true identity and conducted the field interrogation. (You can hear him tell the story in under five minutes here.)

Years later, Rafi Eitan named Aharoni when asked who, in his opinion, contributed the most to the success of the operation. “He found Eichmann and infused us all with the passion of the historic importance of bringing him to trial.” Another team member, Avraham Shalom (later head of the Shin Bet), gave the same answer: “Aharoni did not get enough credit. I think he contributed more than anyone else, even more than Isser [Harel]. He was the driving force.” Meir Amit, Harel’s successor as Mossad chief, described Aharoni as “the major factor in the operation, from its beginning to its end.”

Later, Aharoni led an effort to locate Josef Mengele that, he claimed, might have succeeded had Harel not pulled the plug. He then headed “Caesarea,” the operations branch of the Mossad. Retiring from service in 1970, he did business in Hong Kong and China, ran a private investigation office in Tel Aviv, and finally moved with his English wife to a village in southwest England. There he reverted to his original name (Hermann Arndt), kept chickens, and looked after public playgrounds. He died in 2012 at the age of ninety-one; there were a few British obituaries, none in America.

Aharoni probably never would have told his version if Harel and Malkin hadn’t broadcast theirs. But Malkin, in setting up his own story, had chosen to belittle Aharoni at every turn. A sampling: in his surveillance of Eichmann, wrote Malkin, Aharoni “had made some gaffes that seemed almost beyond invention” and “nearly botched the investigation.” “He was afraid. He was a novice.” During interrogations of Eichmann, “his clipped, precise German, his obvious impatience with much of what he heard, his none-too-subtle air of menace, must have given Eichmann a powerful sense of déjà vu.”

Aharoni now struck back. In 1992 he released his account in the Hebrew press, and in 1996 published a book in German (with the journalist Wilhelm Dietl). A translation appeared the following year under the title Operation Eichmann.

It was an epic score-settling. Malkin, claims Aharoni, was “more a liability than an asset” to the Eichmann operation. He had failed to subdue Eichmann smoothly; instead, the two had wound up struggling in a ditch. And he was “the one member of the team for whom the word discipline had always been without meaning. One could not depend upon his reports. It was always more important to him to tell a good story and crack jokes than to adhere to the bare facts.”

“As far as [Malkin’s] alleged conversations with Eichmann are concerned,” Aharoni wrote, cuttingly,

90 percent of them are just figments of his imagination. The moving and heartrending descriptions of the confrontations between the Jewish kidnapper and the Nazi prisoner were freely invented by Malkin. It would hardly have escaped the attention of the other members of the team if Zvika and Eichmann had constantly been putting their heads together.

How could he be certain? After all, Malkin said he’d kept the conversations secret, and Aharoni wasn’t in the room with Malkin and Eichmann. But Aharoni adds this:

[Malkin] forgets to mention that he and Eichmann had no common language. Zvika’s Yiddish—that was the closest he came to speaking German—was good enough to give Eichmann simple orders and to allow him to use the toilet. It was not sufficient for profound dialogues about the Holocaust. Eichmann, on the other hand, understood neither Hebrew nor Yiddish.

In an interview a few years later, Aharoni was even more scathing: “Even a genius like Einstein can’t speak a language he doesn’t know.” At the time of the operation, Malkin had only Hebrew, Yiddish, “rudimentary English, and an extensive repertoire of profanities in Russian and Arabic.”

Could Malkin communicate meaningfully with Eichmann? In 1996, before Aharoni posed the question, Malkin said in an interview that he had spoken with Eichmann in “broken German and half-Yiddish; he understood well what I meant. I had a lot of time to talk to him again and again.” In 2000, after Aharoni made his accusation, Malkin became defensive: “I knew and know German. Someone who knows German can test me.”

The question, though, isn’t whether Eichmann understood Malkin. It’s how well Malkin understood Eichmann. It was Eichmann’s spin on his deeds that made the purported exchange compelling. German- and Yiddish-speakers can conduct a discussion with a high degree of mutual intelligibility, if they work at it. But could Malkin, with kitchen Yiddish (he grew up in Palestine) and “broken German,” really know that Eichmann was “subtly shading things”? Could he be trusted to remember and convey Eichmann’s words verbatim, as he purported to do in his book? We will never know; the question stands.

It isn’t just the conversations that Aharoni dismisses. Above all, he challenges Malkin’s claim of having persuaded Eichmann to sign the statement agreeing to stand trial in Israel. In this case, Aharoni doesn’t base himself on deduction. This is personal: he insists that he alone dictated the German text to Eichmann, who wrote it out, made an addition, signed it, and gave it back to him. Malkin had nothing to do with it at all.

Did Malkin, in his book, steal credit for something he hadn’t done?

VI. “Of My Own Free Will”

Eichmann’s statement was the axis of Malkin’s account, and for good reason. At the time, Israel attributed great importance to it. In announcing to his cabinet the news of Eichmann’s capture and removal to Israel, Ben-Gurion read aloud to them a Hebrew translation of the statement. Israel later sent a photostat of the original to the Argentine government, and the full text appeared in newspapers around the world, usually under some variation of the headline in the Washington Post: “Eichmann, Snared in Argentina, Went to Israel of Own Free Will.”

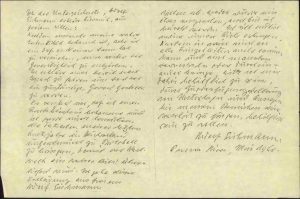

The original, composed in Eichmann’s hand and signed by him, lies today in a police file in the Israel State Archives. This is what it says (I have preferred the translation from German by Hannah Arendt):

I, the undersigned, Adolf Eichmann, hereby declare out of my own free will:

That since now my true identity has been revealed, I see clearly that it is useless to try and escape judgment any longer. I hereby express my readiness to travel to Israel to face a court of judgment, an authorized court of law.

It is clear and understood that I shall be given legal advice, and I shall try to write down the facts of my last years of public activities in Germany, without any embellishments, in order that future generations will have a true picture. This declaration I declare out of my own free will, not for promises given and not because of threats. I wish to be at peace with myself at last.

Since I cannot remember all of the details, and since I seem to mix up facts, I request assistance by putting at my disposal documents and affidavits to help me in my effort to seek the truth.

Adolf Eichmann,

Buenos Aires, May 1960.

The most significant phrase in this statement, repeated twice, is “out of my own free will.” Obviously, no one would believe that a Nazi war criminal would go voluntarily to Israel to stand trial. Obviously, Eichmann would later be sure to say that he signed under duress. As the German investigative paper Der Spiegel noted, Israel was asking the world to believe that “the activity of the Israelis allegedly was confined to making it possible for this former SS lieutenant colonel to make the flight free of charge.”

So why did Eichmann’s abductors go to the trouble of securing the statement in the first place?

Harel proposed one explanation, with himself at the center. In his book, he claims that the idea of having Eichmann sign a document came first to him, at the safe house:

I asked Aharoni to question [Eichmann] about his attitude toward standing trial. It was at this point that I suggested that we try to obtain his written consent to travel to Israel and stand trial there. Not for an instant did I suppose that such a document would have any legal validity when the question was raised of our right to try a man after abducting him to Israel. Nevertheless, I attached a certain ethical importance to such a statement.

That the orchestrator of an abduction should suddenly be troubled with the ethics of seizing someone against his will seems implausible. Nor is it clear what sort of “ethical importance” would accrue to such a document. The point of this version, like much of Harel’s book, was to put the author at the center of everything.

For sheer implausibility, however, Harel’s explanation can’t compete with the one offered in the movie Operation Finale. There, Harel enters the safe house and makes this announcement: “El Al is refusing to send a plane. They say first they need something from us: a signed document from Eichmann saying he’ll willingly come to Israel.”

No doubt, many now believe that this absurd story is true. No doubt, it crept into the plot in order to create a sense of urgency: without Eichmann’s signature, the operation will fail! In film-speak, this is a MacGuffin: a “grail” invented solely to give the protagonists something to chase.

Aharoni gives the most credible explanation. According to him, the idea of a statement by Eichmann had originated with Haim Cohen, at that time Israel’s attorney general and later a Supreme Court justice. Knowing him from past investigations, Aharoni asked him whether he should try to extract a signed confession from Eichmann while still in Argentina. Should Eichmann be pressed to “admit his guilt in connection with the Third Reich immediately? Should I demand a written statement from him?”

Cohen said no; all that was needed from Eichmann was a statement admitting his identity—and, if possible, expressing a willingness to stand trial. “The general formula was provided to me by Haim Cohen,” wrote Aharoni later. “He thought this would facilitate the legal process and might help us if we were caught before leaving Argentine territory.” He might have added that it could also deflect some heat if Argentina erupted in indignation, which of course it did. The statement was meant to buy Israel time and save Argentina face.

So much for why Israel wanted Eichmann’s statement. How did his captors secure it? Given that little happened in the safe house during the nine days of Eichmann’s captivity, his signing of this document is the climax of the story’s long stretch between the abduction and the flight out.

There are two versions, Malkin’s and Aharoni’s. They are utterly irreconcilable.

According to Malkin in his book, Isser Harel decided on the text and had it put on paper. Eichmann wouldn’t sign, insisting he should be tried in Germany. Then, on May 19, 1960, after Malkin had plied Eichmann with wine and cigarettes, and played a flamenco record for him, Eichmann asked for the paper. He was ready:

“May I make an addition?”

“Of course.”

“May I use your pen?”

I handed it to him, then unfastened his leg iron.

Eichmann added an additional paragraph, requesting access to documents.

He looked up. “All right, I’ll sign now.” He paused. “What it says is right. It will be good to be able to explain myself.”

Standing above him, heart leaping, I watched as he wrote, “Adolf Eichmann, Buenos Aires, May 1960.”

Harel was handed the signed statement.

His eyes widened in pleased surprise as he looked it over. “How did this happen?”

“Peter got it.”

He turned to me, smiling. “Good. Excellent work. This is vitally important.”

This scene is dramatically reenacted in Operation Finale. Malkin, paper in hand, descends the steps in the safe house to the living room. The morose team members, despairing that El Al won’t let them on the flight, rise to their feet. He holds up the paper. “You did it!” says the woman who’s been introduced as Malkin’s love interest.

And then there’s Aharoni’s version. In his book, he describes asking Eichmann if he would agree to stand trial. When Eichmann proposed that he do so in Germany, Austria, or Argentina, Aharoni reacted firmly: “You can’t be serious. You insult my intelligence. . . . It will be either Israel or not at all.” The next day, Eichmann said he’d reached a decision and was prepared to come to Israel.

“Would you give me that in writing?”

Eichmann agreed. I took his goggles off and gave him a ballpoint pen and paper. Together, we formulated his confirming statement in German. I dictated my draft. Where he had no objections, he wrote it down slowly sentence by sentence, just as if he were in deep thought. The final sentence was his alone. . . .

As he signed, he asked me for the date. He had obviously lost all sense of time. That was fine with us. We wanted this to remain that way, one more factor in the psychological pressure we were exerting.

I said to him: “Just write Buenos Aires, May 1960, that will be enough.”

He did so and handed me the letter with a faint smile. His expression seemed to be saying: “Now my fate is sealed.”

VII. Truth vs. Drama

There is no way to split the difference between these two accounts. Either Malkin stood above Eichmann as he wrote, signed, and dated the statement, or Aharoni did. Faced with such competing claims, one is tempted to conclude, as with so much else in this story, that we cannot know.

A recently published document, however, shifts the answer far to one side. I’m proceeding here from a premise few historians would dispute: as a rule, internal memoranda that are close in time to an event are probably more constrained by fact than memoirs published decades afterward. It’s why historians eagerly await the opening of archives.

In 2012, the Mossad authorized the creation of a roving museum exhibition on Eichmann’s capture. Its curator, Avner Avraham, a former Mossad agent, went through the Mossad’s “attic” and assembled a medley of artifacts and documents: the negatives of the surveillance film of Eichmann before his capture, the goggles placed over his eyes, the list of items found on his person, the syringe used to sedate him before his transfer to the El Al flight, fake passports, and more. The exhibition was launched at the Mossad headquarters, and then proceeded to the Knesset and the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv, before departing for an American tour. (Its final stop is now at the Holocaust Memorial Center in a suburb of Detroit.)

Among the artifacts on display is a nondescript item that most museum-goers, especially Americans, have likely skipped over quickly: a one-page, typed Hebrew document, signed by Zvi Aharoni. Marked “top secret,” it is headlined aide-mémoire in Hebrew. The provenance of the document is given as the Mossad Archive. It’s not dated, but the exhibition catalogue puts it in 1960.

Why did Aharoni write it? Or why was he prompted by his superiors to write it? The state of Israel was about to make public use of Eichmann’s statement, and many would assume that it had been coerced. Aharoni’s superiors wanted to know exactly how Eichmann’s statement had been secured. Aharoni prepared his account immediately on his return to Israel.

Here is the text (in English for the first time):

On May 16, 1960, I saw Adolf Eichmann where he was being held, and we had a conversation. I asked him, inter alia, whether he was sincerely prepared to make good on what he told me on a prior occasion, that he has accepted his fate and is ready to do everything to clarify certain facts about a certain period, for the benefit of history.

Eichmann answered in the affirmative, and I asked him whether he was prepared to travel to Israel of his own free will, in order to stand trial there. Eichmann answered in the negative to my additional question, and explained that in certain conditions he was willing to travel to West Germany or Austria to stand trial, but not anywhere else.

From the conditions that Eichmann set, I understood that he wanted to elude the whole matter [of a trial], and I told him so, and so I asked him if he wanted time to think about my proposal. Eichmann agreed, and I met with him the following day, May 17, 1960, where he was being held. Again I asked him if he was willing to go, of his own free will, to Israel in order to stand trial. He replied in the affirmative, and agreed to sign a declaration to that effect. I dictated to him a declaration that I had prepared in advance in German, and at its end I asked if he wanted to add anything at his own initiative, and I explained to him that he was free to add anything he wished. Eichmann responded in the affirmative, and at his initiative he added the last sentence that appears in the declaration.

Eichmann signed the two pages at my request, and I initialed and dated the back.

Here, then, we have the closest thing to a real-time account of how Eichmann came to sign the statement.

Aharoni’s aide-mémoire is supported by the original of Eichmann’s statement. It wasn’t just signed by Eichmann; he wrote the entire two-page statement in his own hand and signed it at the bottom of each page as one would sign a legal document. (I have been unable to consult the reverse side.)

So Malkin’s account, which has Eichmann signing a pre-prepared statement left on his bed, cannot be true. Someone capable of composing a legalistic text in German must have worked with Eichmann and dictated the desired content so that he could write all of it. That could only have been Aharoni. His “top secret” aide-mémoire, written for internal use and not for public consumption, settles the matter, and its inclusion in a Mossad-sponsored exhibition sends the same message.

There are more aspects to the question, but they would take us deep into internal Mossad politics of the 1960s, which swirled around Harel. In brief, Aharoni split with Harel; Harel’s account favored Malkin; Aharoni would call Harel’s book “a detective novel. . . . Isser settled accounts with people by not giving them the credit they deserved.” Two of the agents from the safehouse strongly supported Aharoni’s version. But all of this later testimony is remote from the event by fifteen to 30 years. The 1960 document is the clearest evidence yet that Aharoni’s version, not Malkin’s, is truer, if not the truth itself.

Why does it matter who took Eichmann’s statement? Part of the answer may be found in the lesson that the actor Oscar Isaac, cast as Malkin in Operation Finale, believes we should take from Malkin’s supposed success:

Malkin showed empathy and kindness to Eichmann, and it was through that that he was able to get Eichmann willingly to sign a confession and willingly go to Israel to stand trial. I hope that people do see that and take that [in]. How to deal with evil and those that are truly guilty of horrible things . . . the most effective way is not necessarily through equal amounts of hate, but through dialogue and understanding.

This essay is not the place to argue over how most effectively to deal with evil. (It’s hard, though, not to recall that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain proffered the same argument as Isaac’s after he procured Hitler’s signature on a piece of paper in September 1938.) If, however, Malkin’s account is false, then Eichmann’s actual behavior in the safehouse gives not an iota of support to Isaac’s claim of how best to deal with evil. Eichmann surrendered, instead, to “psychological pressure” (Aharoni’s term), practiced by a master interrogator who, by his own count, had conducted “hundreds” of interrogations of Germans, Arabs, and Jews. The official Shin Bet website bluntly asserts that Eichmann signed to avoid being liquidated. (Aharoni, it will be recalled, told Eichmann: “It will be either Israel or not at all.”) If Aharoni, not Malkin, extracted the statement from Eichmann, then the idea that “empathy and kindness” speak to the hearts of the evil and the guilty will have to find supporting evidence elsewhere.

There is a larger issue still. If Malkin imagined or fabricated his role in securing Eichmann’s signature, then what should we make of his alleged secret conversations? Could they, too, be the fabrications of a serial fabricator?

Each reader will draw his own conclusion. But any dramatic production that bases itself on Malkin’s version must be subject to the same doubts as the version itself. And if the signing episode is its dramatic fulcrum, as in Operation Finale, then it is based on fiction, not fact.

It’s not as if those involved in Operation Finale didn’t do their homework or know the risk. The writer, Matthew Orton, certainly did. He read all of the versions, identified “inconsistencies,” but then claimed to hew “very close to what actually happened.” Weitz also made a strong claim for the veracity of the film. He admitted to small adjustments, to compressions of time, and to switching the gender of one of the team members. But “if you get things wrong,” he warned, “it can be as bad as providing fodder for Holocaust deniers.”

Weitz had a caveat, however: Eichmann’s captors, he said, “often contradicted each other, which gives you a choice to make in terms of what’s the truth and what is more dramatic.” This is the “buyer beware” label on all Hollywood treatments of history. It’s not the same as the relativist position that all truths are equal. It’s that the most cinematic treatment is the truest. That’s why Malkin’s version has always prevailed over Aharoni’s; after all, from the outset it was deliberately compiled as a drama.

Weitz must have known that, too. He acknowledged that while Malkin was a heroic figure, he “was also a charmer, a seducer, and a bit of a con artist.” Operation Finale went into this with eyes wide open. Audiences didn’t.

VIII. The Incidental Virtue of Truth

I’ve maintained that the cinematic Eichmann is a distortion, based as it is on the nine days of Eichmann’s life spent in captivity in Argentina. Those nine days became the subject of cinematic fascination thanks to an account that itself may well be a fiction and that became the most easily exploited loophole in the Eichmann story. Growing ever bigger, in Operation Finale it gave Eichmann a posthumous victory. From smaller than life in the glass booth, he went, impressively, to larger than life on the silver screen.

In fairness, not all of this can be laid at the door of Malkin: his purported conversations with Eichmann seem sparse in comparison with their cinematic versions, adorned with intricate, cut-and-thrust dialogues. Operation Finale even gives Eichmann a joke to tell, to demonstrate his humorous (and human) side. Here the film betrays even Malkin, who wrote that Eichmann suffered from “an utter lack of humor.” But the artistic license Malkin gave himself grew ever larger in each subsequent iteration of his story by others, until in Operation Finale it crossed a line—albeit one that would be drawn differently in Israel from the line drawn in America.

There is good reason that this latest Eichmann, the Weitz-Kingsley one, caused a Jewish audience to stir uneasily in its seats in Manhattan, and for Israelis to shun him entirely. The latter were put off not by the human Eichmann or the diabolical one but by the charming one. Charisma wedded to anti-Semitism has a baneful history as the prime vector for anti-Semitism’s spread to the masses. Yes, the Eichmann films load up on images of Jewish suffering. But can these really outweigh the portrayal of a likable anti-Semite, especially in today’s environment when anti-Semitism has struck roots among educated elites and in some countries among significant portions of the larger populace?

The Vienna-born Teddy Kollek, who was both charming and brilliant, had met Eichmann in 1939 and would orchestrate the logistics of his trial in 1961. He described him, Nazi uniform notwithstanding, as “an insignificant individual—who could well have ended up as a petty clerk.” This may be why Ben-Gurion decided to make Eichmann the centerpiece of a media-saturated trial—because he would be a foil.

“Adolf Hitler should be given precedence over Adolf Eichmann,” Ben-Gurion instructed the prosecutor, “even though Eichmann is the defendant.” A Kingsley-like Eichmann in the glass booth would have inverted the proceedings, and made the trial solely about the man (as Arendt erroneously thought it should be). Likewise, a film starring a “charming” Eichmann is destined to be more about the man, and less about the Holocaust.

Now, after Operation Finale, the Malkin-inspired mode of representing Eichmann has probably spent itself. Yet it’s a story that has to be told anew in every generation. As Kollek said of the trial, its effect “cannot be maintained all the time. . . . Every one of us forgets.”

Is there a way forward? To set the historical record straight, I propose that the next filmmaker or playwright give us the story through the lens of Zvi Aharoni. A small start has been made: the surveillance and abduction of Eichmann are told from Aharoni’s vantage point in a gripping animated short, The Driver is Red (2017). A full-scale production would have three advantages. First, it would be more compelling: Aharoni, according to the team, was the “driving force.” Second, it would rectify the injustice done to him. Third, with regard to Eichmann, it would have the incidental virtue of being true.

More about: Adolf Eichmann, History & Ideas, Holocaust, Israel & Zionism, Mossad, Movies, new-registrations