Simply by virtue of its focus on German-Austrian art from 1890 to 1940, the walls of New York’s Neue Galerie, founded by the philanthropist Ronald Lauder, can unnerve a visitor with their uneasy mix of visions of beauty and images of radical disruption. The museum’s most recent show, Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s, which closed on May 28 after a three-month run, made the discomfort of that juxtaposition all the more explicit.

The nearly 150 canvases, photographs, and graphic works in the exhibit formed a collage of artistic responses to fascism and Nazism—running the gamut from open resistance (in vivid scenes of street fights) to seeming complacency (in placid scenes of nature) and from acerbic satire (in the visages of ghoulish soldiers dressed in garish, circus-like uniforms) to surreal horror (in still lifes spawning monstrous growths) to lyrical odes to an idealized Aryan perfection (as in a portrait of a young male swimmer in a pose anticipating today’s underwear ads).

Some artists were well-known, others less so. Their multiplicity of styles and influences underscored not just how varied were their individual visions and aesthetics but also the intertwined layers of veracity, ambiguity, and deception that, given the historical circumstances, their works seem simultaneously to express and to conceal.

This exhibit was the third in a trilogy mounted by the Neue Gallerie in recent years, each one focused on a different moment or aspect of modern German history. The first, in 2014, was Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany 1937; the “attack” in question was encapsulated in the 1937 Nazi-organized exhibit in Munich of 650 works of so-called decadent art—a category that included any work by a Jewish artist—confiscated from German museums by Hitler’s agents. A year later came Berlin Metropolis: 1918-1933, exploring the increasing political, social, and artistic divides of the Weimar era. All three exhibits were organized by Olaf Peters, a German art historian who also edited and contributed to the catalogs.

The predominant feeling throughout Before the Fall was of watching a nightmare unfold through the window of an artist’s studio. Perhaps the prime example was the landscape Expectation, painted in 1935-36 by the surrealist Richard Oelze (1900-1980). About two dozen men and women, seen almost entirely from the back, crowd together in the painting’s foreground, their heads tilted upward as if waiting for something to appear from the sickly-looking, greenish-brown sky that commands their attention. The men all wear trench coats that look cut from the same cloth; only their hats differ, with some wearing fedoras and others bowlers. Of the women, only one sports any kind of decorative element: a rust-red flower on her hat and another on her coat. Are these ghoulishly lighted figures even human? An eerie glow emanates from the overgrown stalks, plants, and trees that surround them.

No less dread-inducing, for any Jewish visitor with a sense of history, were numerous other works on exhibit, artifacts of an era about to explode with catastrophic force in the Nazis’ all-out attempt to accomplish the “final” extermination of the Jewish people. For that reason, although the exhibit did not make a point of it, and neither did most reviewers, it seems to me especially pertinent here to attend to the show’s small but intriguing selection of work by six Jewish artists.

Not all of the six artists who gave us these snapshots, as it were, from the edge of the abyss survived the Holocaust; nor do we know how much of their art perished with them. Of most, not enough is known or has been studied to provide more than a brief sketch of their lives and work. But Before the Fall did at least offer an opportunity to rescue them from obscurity.

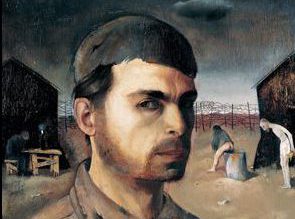

Three of the six, beginning with Felix Nussbaum (1904-1944) were highly accomplished and are somewhat better known. In his unforgettable Self-Portrait in the Camp, from 1940, painted shortly after escaping from a French internment camp where the Gestapo had sent him, Nussbaum appears in tattered prison uniform against a queasy colored sky and a backdrop of barbed wire and a feces-smeared can where an inmate is seen defecating. Over the next four years, which he and his wife spent in hiding, he continued to produce haunting images tinged with the surreal—of whose all too palpable reality his very existence had become an emblem. In 1944 the Nussbaums were captured and sent to Auschwitz, where they both perished.

The artist and designer Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898-1944), who also perished at Auschwitz, is remembered not only for her art but for her tenacity in giving art lessons and inspiring hope among the children of Theresienstadt, where she and her husband were first deported in 1942. Years earlier, in her hometown of Vienna, she had been arrested for activism as a Communist—an experience reflected in her painting The Interrogation II from 1934-1938, which portrays an almost faceless prisoner whose eyes have been blacked out and whose mouth, nose, and hands are smudged with red. Also in the exhibit was her post-1936 Still-Life with Toys, Flowers, Child’s Drawing, Plate, Spoon, and Alphabet Card, whose named objects are grouped together to form a color-splashed shrine to lost childhood; the Scrabble-like cubes in the foreground spell out Mut Zu, a reminder to have courage.

Taking a different and more peripatetic turn was the life of the avant-garde photographer Helmar Lerski (born Israel Schmuklerski, 1871-1956). A native of France, he discovered photography after emigrating to the United States at twenty; returning to Europe in 1915, he became a well-known cameraman (working on films like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) and portraitist. By 1936, the date of five dramatically lit black-and-white portraits at the Neue Galerie exhibit, he had settled in Palestine, where he produced, among other works, the series Working Man and Jewish Soldiers. After World War II he took up permanent residence in Switzerland.

What we know of the remaining three is quickly told.

*The photographer Erwin Blumenfeld (1897-1967) escaped Europe for the U.S. in 1941; his 1932 photograph of Hitler, taken a year before his assumption of the German chancellorship, is superimposed with red ink dripping from the eyes and mouth, giving the aspiring dictator the appearance of a stylized vampire.

*The painter Hans Ludwig Katz (1892-1940), whose work was denounced by the Nazis as degenerate, fled to South Africa where he died in 1940; his Eye Operation, in which disembodied hands target a man’s eyes, seems to signal the destruction of the artist’s vision.

*Finally, in Street Battle, a 1930 painting by Erika Giovanna Klein (1900-1957), a violent clash between soldiers and demonstrators is depicted in pastel colors that belie the brutality of the action; leaving Europe for New York in 1929, Klein devoted the rest of her life to teaching.

Exhibitions of any of these artists’ works have been spotty to non-existent. New York’s Jewish Museum mounted important retrospectives of the work of Nussbaum in 1985 and of Dicker-Brandeis in 2004. (In 1998, Nussbaum’s native German town of Onasbruck opened a Felix Nussbaum Haus, designed by Daniel Libeskind, to showcase his work.) Currently, the Paris Jewish Museum has hosted the first exhibition in France of the work of Helmar Lerski. But since 2001’s Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory, at London’s Imperial War Museum, I’m unaware of any larger survey of the works of Jewish artists of the Holocaust era.

Organizations like Pro Music Hebraica and the Milken Archive of Jewish Music have done heroic work in rescuing and giving fresh life to forgotten and/or suppressed works of Jewish musical art from the 20th century. The Milken initiative specializes in the American scene, itself greatly enriched by refugees from persecution under Nazis and Soviets. Jewish visual art from the same period and environment deserves no less. In offering a taste, Before the Fall cries out for a more ambitious undertaking.

More about: Arts & Culture, Holocaust, Jewish art