The vision of the word of the Lord to Israel in the hand of My messenger.

I loved you, says the Lord. But you say, “Wherein have You loved us?”

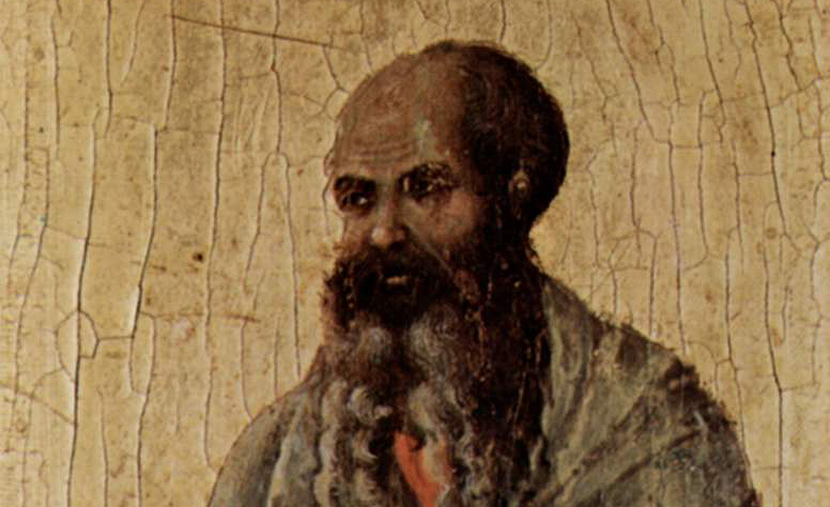

So begins the book by the last prophet in the Jewish tradition, the final part of which is read on the Sabbath before Passover. There is some dispute as to whether Malachi, the name of the book, refers to the actual name of a prophet or simply means “my angel” or indeed “my messenger” as I choose to translate it here.

What about this book persuaded the rabbis that it marked the end of the prophetic era and the switch to a totally different medium—namely, that of rabbinic legal and moral guidance—for conveying the word of the Lord?

Son shall respect father and the servant his master.

But if I’m a father, where’s My respect?

And if I’m the master, where’s My fear?,

Says the Lord of Hosts.

As for you, priests who despise My name—

But you say, Wherein have we despised Your name?

Serving on my altar disgusting bread.

But you say, How did we disgust You?

By saying the table of the Lord is despicable.

For when you offer a blind animal as a sacrifice, is there no harm?

And when you offer a crippled or sick one, is there no harm?

One thing you can safely say about this particular book of prophecy: it takes a dim view of the priests and their guidance of Jewish national life from the Temple that stood at the heart of that life. No, the Lord isn’t too happy with how things have been going with the priests lately.

For the lips of a priest should keep knowledge

And the law should be sought from his mouth.

For he is an angel of the Lord of Hosts.But you have turned from the path,

Caused the multitude to err in the law,

Corrupted the covenant of the Levite,

Says the Lord of Hosts.

* * * *

Here I send My angel and he’ll clear a path for Me

And all at once there’ll come to His hall

The master you are seeking

And angel of the covenant you’re wanting.

Here He comes now, says the Lord of Hosts.

But who can bear the day He comes

And who remain standing on seeing Him?

For He is like a smelter’s flame

And a launderer’s lye

And He’ll sit and smelt and purify silver

And purify the Levites and refine them like gold and like silver.

And who remains will be for the Lord bearers of offerings and charity

And the offering of Judea and Jerusalem will please the Lord’s palate

As in the days of old and former years.

The general thrust of this book is that the priests are corrupt and will be replaced. But by whom? Who is this messenger who will come bearing a new truth that is also the old truth? Who will restore judgment to its true role of providing justice?

In the view of Rachel Elior, professor of Jewish mysticism at the Hebrew University, the late-Second Temple period—which followed Malachi by some three centuries and leads up to the rabbinic period—saw three distinct groups vying for control of Judaism. One was the priestly ruling class from the house of Zaddok, known as the Sadducees, who were descended from the priests referred to here. Another was the Hasmonean priestly family, who, although not descended from Zaddok, were nevertheless sufficiently gifted in battle to gain physical control of the Temple and unite priestly and political authority for over a century under Seleucid and Roman rule.

And lastly came the Pharisees, from whom rabbinic Judaism emerged and who, Elior writes, were “not priests and not interested in the hereditary legitimacy of the biblical priestly order, but rather sought to found new sources of authority on a different basis.” That basis was “the revolutionary idea of the Oral Law,” which “is not founded upon the unique divine inspiration reserved for prophets, poets, priests, and Levites, not limited to a written text and not kept by the priests, but rather emphatically put forth by persons lacking in tribal connections who are regarded as possessing a tradition, experience, and discretion worth taking into account.”

When the Romans took over Judea, they imposed a new calendar. The Pharisees wanted their own calendar, different from both that of the conquering Romans and that of the ousted Sadducees, and introduced their own new-year festival of Rosh Hashanah, which we still have today. Meanwhile, according to Elior, a group of Sadducees had long since decamped for Qumran where they continued to produce the same sort of prophetic works that had been the norm until then—but these were no longer accepted as the message of the Lord to the people but instead defined as mystical works. A prime example is the story of the chariot that transports the prophet Elijah to heaven—which, the Pharisees declared flatly, “we do not teach . . . unless [the teacher] is a wise man who knows his own mind.”

And with that, prophecy was silenced. On what grounds was it silenced? On the grounds that the priests were corrupt and a new messenger was at hand: a new messenger able to judge.

But I will draw near you to try

And I will be a witness to chivvy

The warlocks and adulterers and bearers of false witness

And the swindlers of day laborers, widow, and orphan,

And swayers of the sentence of the stranger.

But they won’t see Me,

Says the Lord of Hosts.

For I am the Lord, I have not changed

And you are the children of Jacob and have not ceased being;

Since the days of your forefathers you’ve turned from My rules and not kept them.

Return to Me and I’ll return

To you, says the Lord of Hosts.

But you say, In what shall we return? . . .Bring all the tithe to the counting house

And let there be food in My mansion

And test Me with that, says the Lord of Hosts.

If I do not open you the silos of heaven

And empty for you blessing till beyond saying when. . . .For here the day comes burning like a furnace

And all the connivers and doers of wickedness are straw

And they’ll be scorched on the day that comes,

Says the Lord of Hosts, that won’t leave a root or branch.

And a sun will rise for you who fear My name,

Redemption and relief in its wings,

And you’ll go out and caper like calves in the field.

And you’ll trample the wicked for they’ll be ash under the soles of your feet

On the day I’m making, says the Lord of Hosts.

Remember the law of Moses My servant

That I commanded at Horev for all Israel, laws and statutes.

Here I Myself am sending you Elijah the prophet

Before the coming of the Lord’s day great and terrible.

He’ll turn the hearts of the fathers from against sons

And hearts of sons from against fathers

Lest I come and smite the land to desolation.

That last message of the book of Malachi is one of hope and social unity. Though the rabbis opted to repeat the line about the promise of Elijah coming with a promise of redemption, so as to avoid ending the book on the threat of desolation, the actual promise is one not of pie-in-the-sky redemption but of putting fathers and sons back on the same page: an end to civil war.

The rabbinic tradition does not overtly record the social and religious upheaval being adumbrated in Malachi. But talmudic tradition has it that after Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, “the divine spirit left”—that is, prophecy ceased to occur. The next recorded instance of a heavenly voice is connected with Yavne, the Galilean city where Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai renewed Jewish learning after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. But there are hints of the conflict referred to in Malachi in a thousand diverse stories like this one:

They would contaminate the priest who was burning the red heifer

For fear lest the Sadducees say it was burned at dusk.

And there’s a tale of one who’d waited till dusk and came to burn the heifer,

But Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai knew of it and came and laid two hands on him

And told him, “My dear man, High Priest, how fit are you now to be High Priest?

Dip yourself this one day.” He went down and dipped and came back up again.

After the priest came back up he nicked his ear.

He told him, “Ben Zakkai, when I have a chance to deal with you. . . .”

He told him, “When you have a chance. . . . ”

It wasn’t three days before they put him in the grave.

His father came before Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai. He said: “My son never had a chance.”

(Tosefta, Parah 3:5)

Here in this snapshot we see recapitulated all of Malachi’s complaints about priestly malfeasance, plus a demonstration of the cure. According to the Pharisees, the priest performing this ritual must burn the heifer before dusk, after first immersing himself. At least that’s the explicit point of contention. More crucially, Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai also perceives that the priest is diseased, like the blind or sick man who Malachi charges has brought an offering. That is why he nicks his ear, making him obviously flawed and so unfit to serve. The death that arrives swiftly is not divine retribution but the result of the disease that Rabbi Yoḥanan, the representative of the new priestly caste, has discerned.

In brief, the task of the priest was to detect sickness not only in the leper (as outlined in this week’s Torah reading) but in, as it were, his own house. Priests are the physicians of the soul. By exposing this particular priest as unfit to be High Priest, the tale invests authority in a new and unerring standard of judgment personified in Yoḥanan ben Zakkai, the founder of post-Temple Judaism. The voice of prophecy had been stilled but the Eye above still saw. Judgment was no longer susceptible of prejudice on the grounds of ancestry, and the voice of judgment went out of the Temple to become available to everyone.

More about: Malachi, Prophets, Rabbis, Religion & Holidays