Atar Hadari

Atar Hadari’s Songs from Bialik: Selected Poems of H. N. Bialik (Syracuse University Press) was a finalist for the American Literary Translators’ Association Award. His Lives of the Dead: Poems of Hanoch Levin earned a PEN Translates award and was released in 2019 by Arc Publications. He was ordained by Rabbi Daniel Landes and is completing a PhD on William Tyndale’s translation of Deuteronomy.

Esther Shows How to Speak Your Mind Without Undermining Social Order

The star of this week’s Purim story gets her point across because of the way she tells certain truths.

Did the Rabbis Think the Maccabees Were Too Militaristic?

The problem was not that the stars of the Hanukkah story were too heroic, but that they confused their military heroism for the capacity of communal leadership.

The Significance of Supplication

An ancient rabbinic dispute pitted eminent scholars against one another. The Taḥanun prayer is rooted in that story of public shame and private distress.

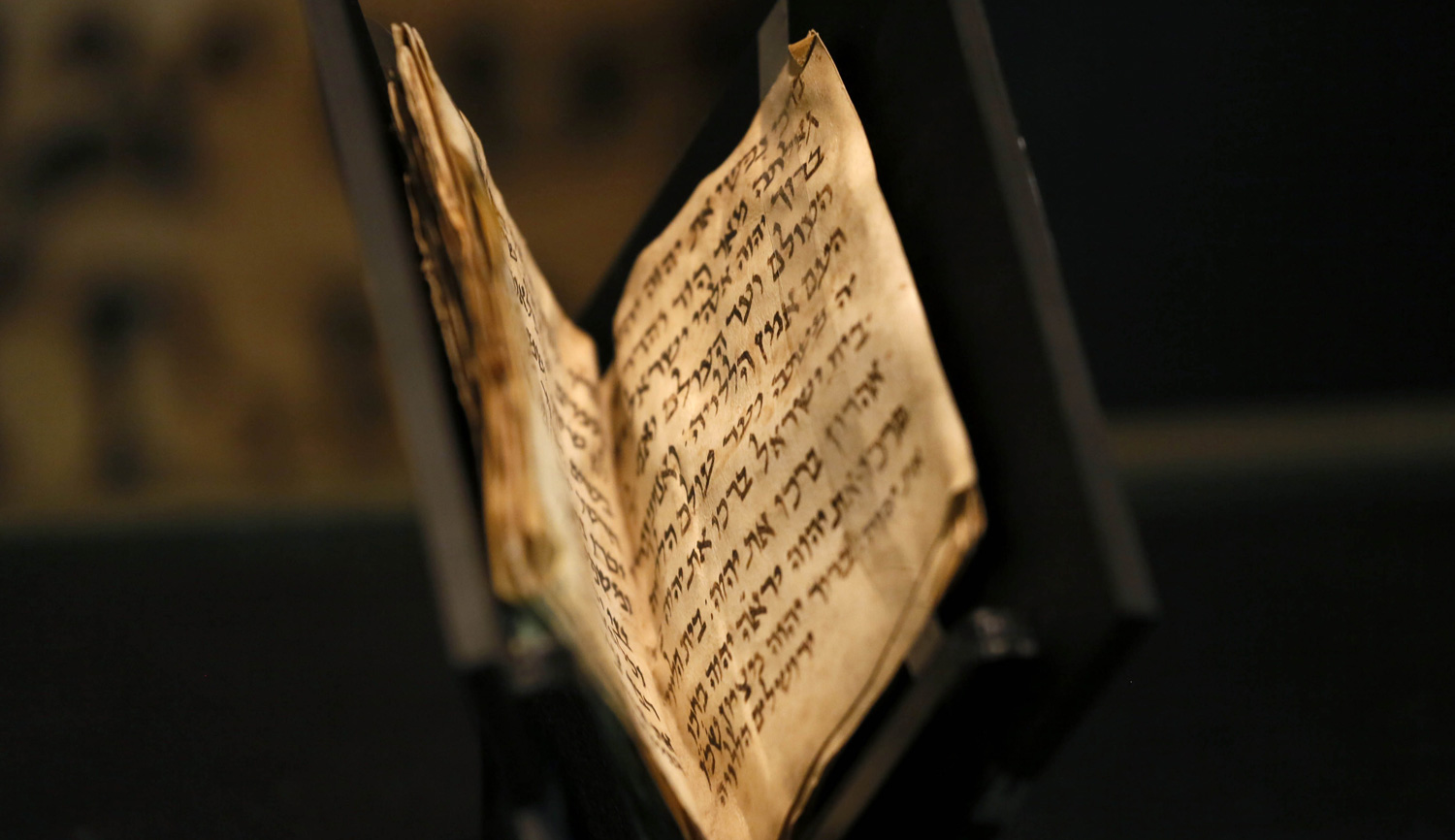

A Blueprint for Jewish Law

A passage in the Talmud’s first tractate shows why it’s such a uniquely influential work, and so unlike anything in the history of Western literature, theology, or legal scholarship.

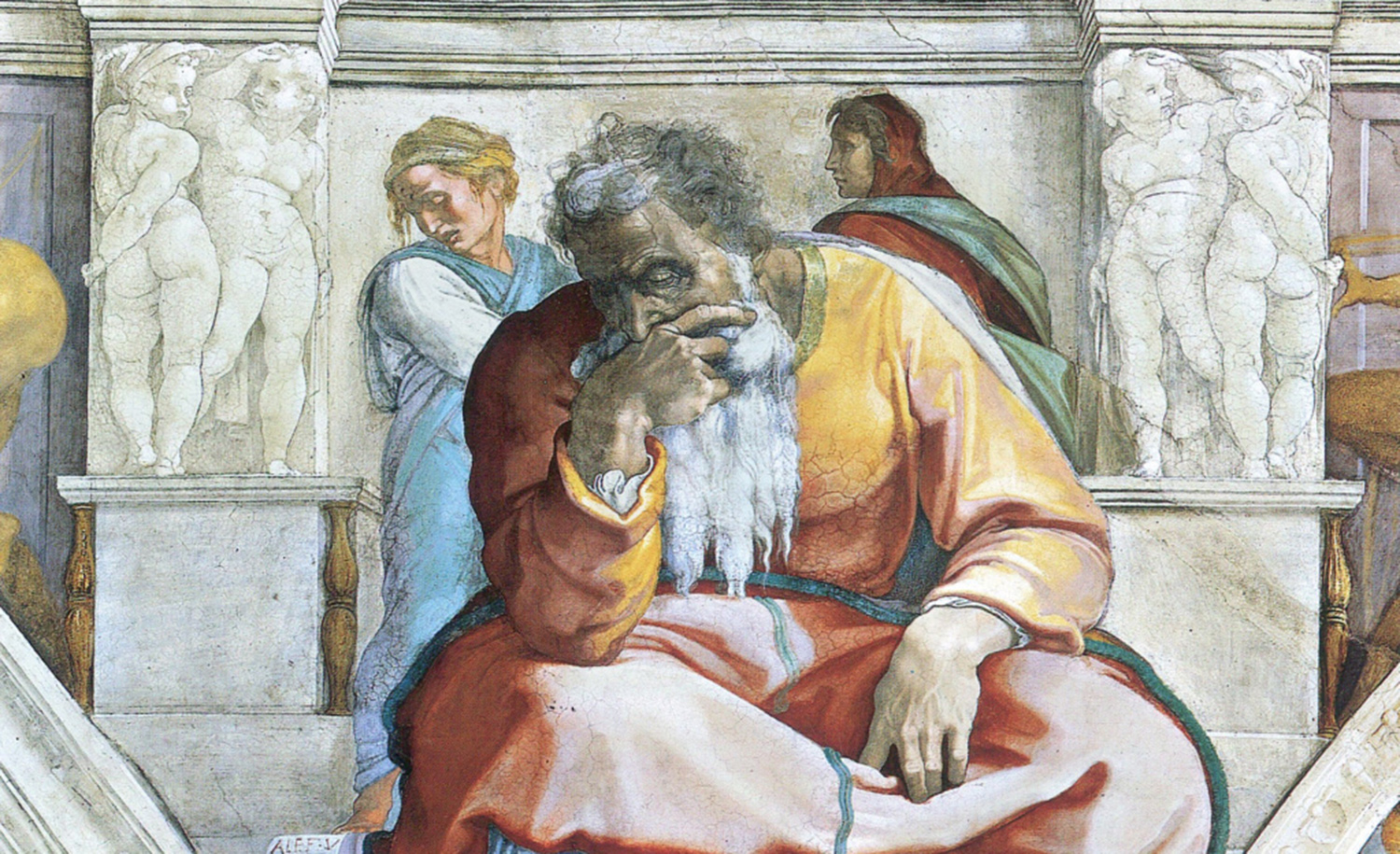

Bookends to the Jews' First Experience with Statehood

Moses inaugurated Jewish national independence. The prophet Jeremiah comes to oversee its collapse.

The Upside-Down, Perfectionist Prophecy of Jonah

Jonah is the anti-Moses: a prophet who wants to persuade the Lord that some people are that bad and should be made to pay for their sins.

What Contemporary Judges Can Learn from the Judges of Yore

No judge is so great as to be exempt from showing deference to the judicial hierarchy at large.

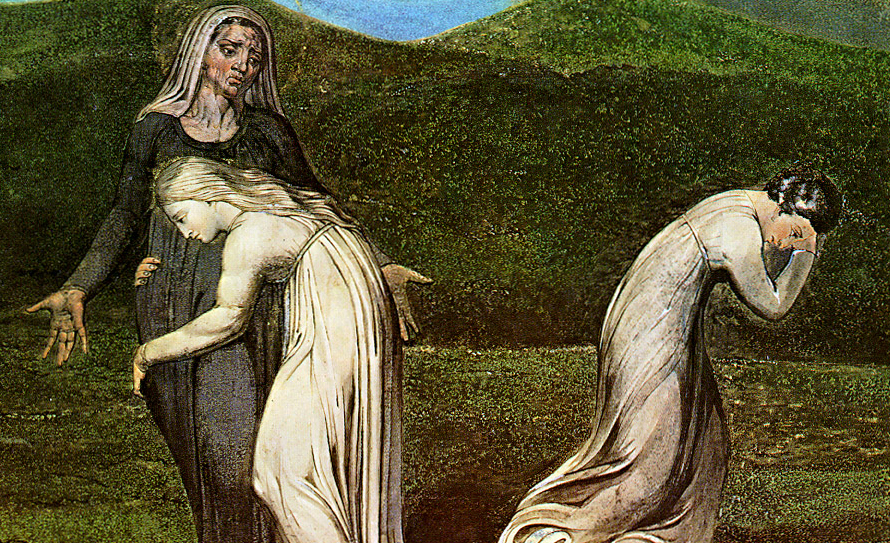

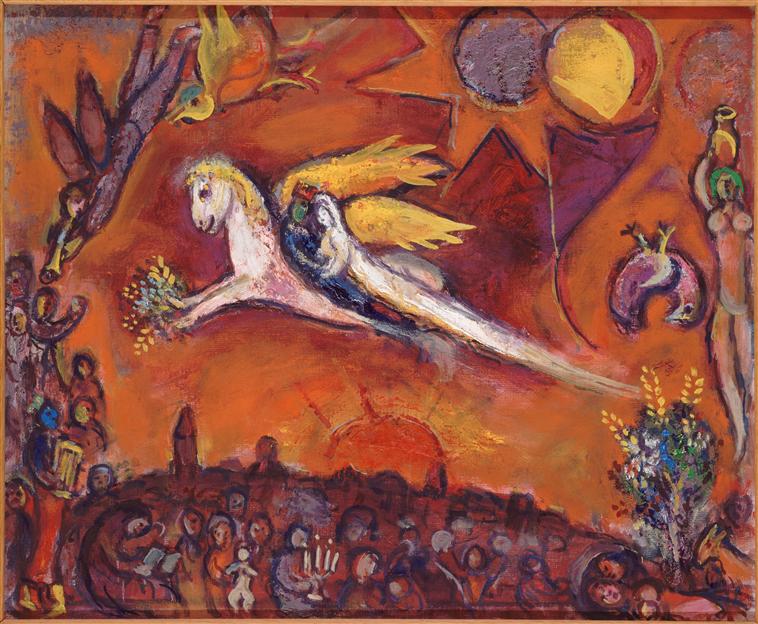

How the "Jewish National Poet" Revitalized an Ancient Literary Form

The great Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik’s “Scroll of Orpah” retells the story of the book of Ruth from another perspective.

All the Reasons Why You Don’t Want a Career in Prophecy

Just after his moment of glory, the prophet Elijah finds himself alone and deserted.

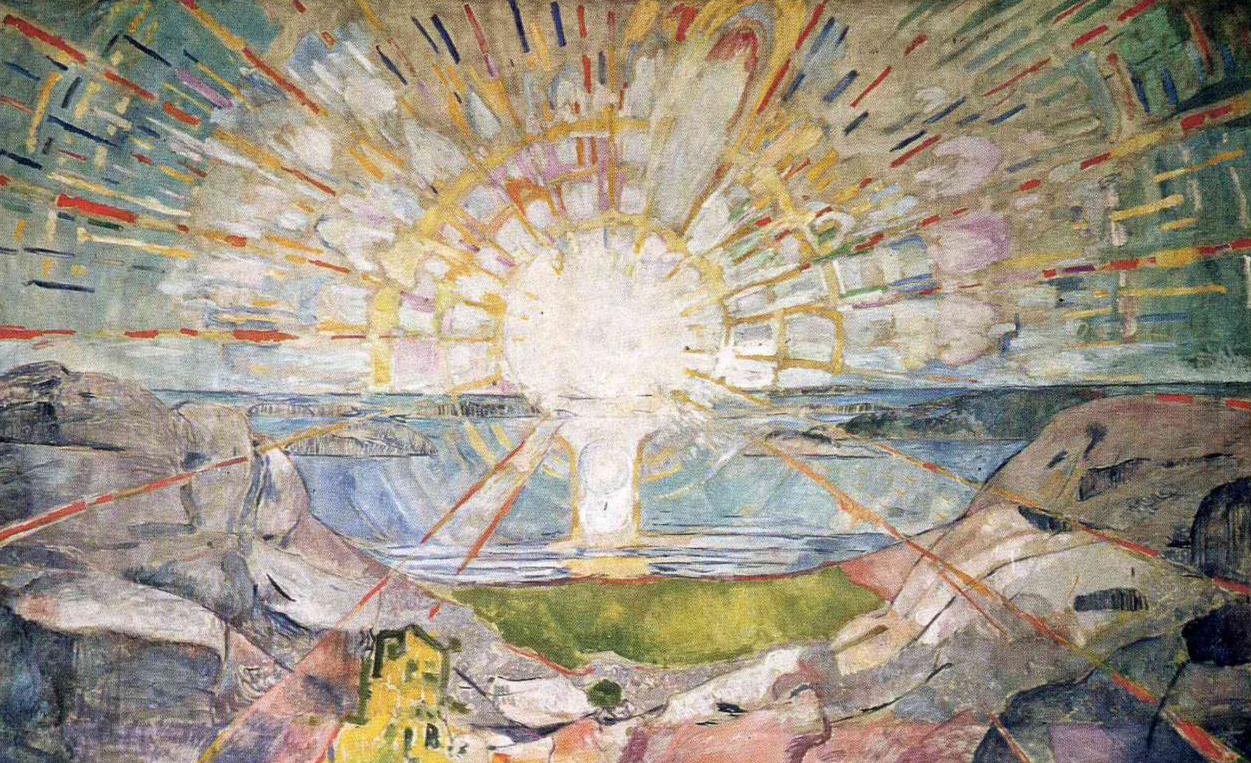

A Pagan-Seeming Blessing in the Daily Prayers

Why do Jews praise the great lights?

Of a Widow, a Patroness, Their Stricken Sons, and Two Hebrew Prophets

What a pair of parallel stories tells us about gratitude and awe.

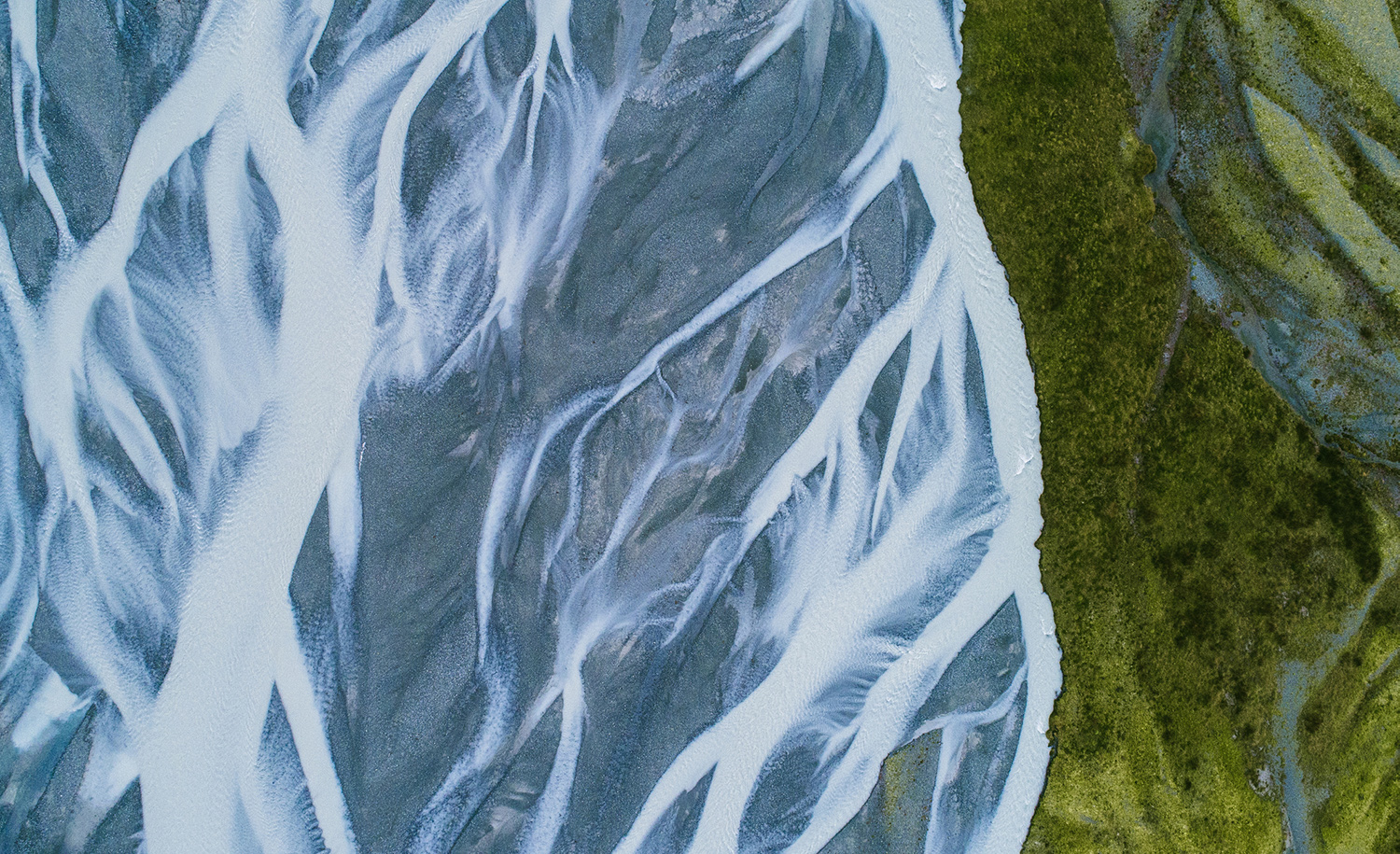

Why Judaism Takes Rain Very Seriously

The land given to the Israelites provided ample space for crops and livestock, but there was a catch: the water doesn’t come for free.

The Prophet Whose Glorious Words Permeate Jewish Consciousness

Isaiah’s unforgettable language serves much the same role in spoken Hebrew that Shakespeare’s does in English.

Is There a Physical Reality to God?

That’s the question raised by a poem sung at many Ashkenazi services.

The Happiest Psalm of Them All

In a biblical book many of whose poems express anxiety and apprehension, Psalm 104 is a confident and joyous singalong.

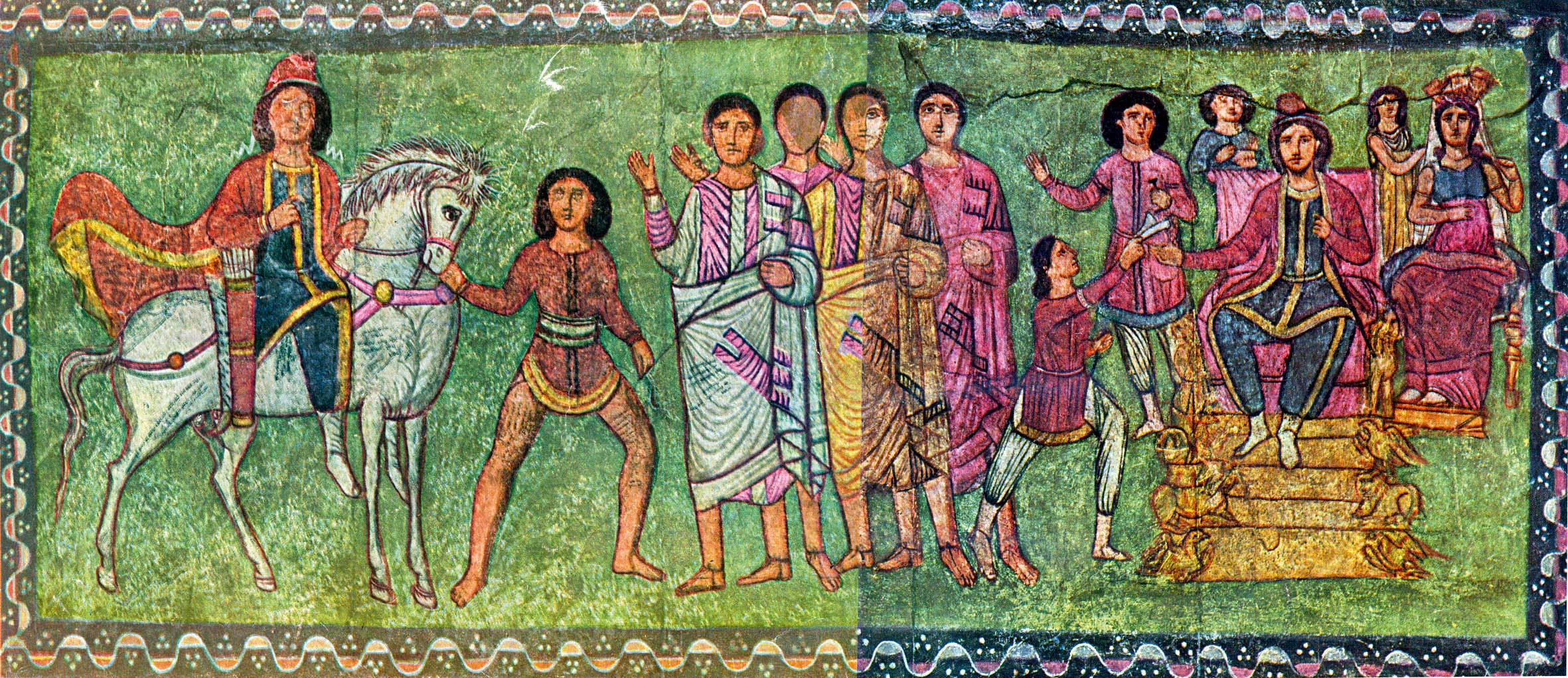

Joseph vs. Moses: A Comparison

One engages in dialogue with his fellow Jews, and one engages in a dialogue with God. What’s the meaning of the difference?

Who is Serenaded on Friday Night: the Woman of the House, or the Divine Presence?

Before the meal on Sabbath eve, the prayer book offers a song of praise to the ideal woman.

Why Some Rabbis Have Loved the Sabbath Prayer "Shalom Aleykhem"—and Some Haven't

The promise and peril of calling angels to bless your Sabbath table.

The Sh'ma Is the Jewish Safety Net

The brave attempt at monotheism was bound to go wrong sometimes, and when it did, the Israelites would need help putting the pieces back together again.

Benzion Netanyahu, the Altalena, and Me

Looking back at the founding moments of the state of Israel with the father of the current prime minister.

The Case of the Non-Jewish Prophet

With his fatal weakness for the lure of fame and fortune, the prophet-for-hire Balaam seems completely our contemporary.

Two Anthem-Like Views of What Judaism Boils Down To

The two great liturgical songs of Yigdal and Adon Olam offer rival attempts to summarize the essence of Judaism.

Why the Lord Doesn't Allow David to Build the Temple

David remains a revolutionary hero, a guerrilla leader and desert tribal bandit—too much of a renegade at heart to be entrusted with His house.

The Darkest Day in the History of Judaism?

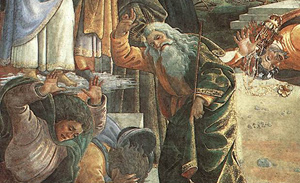

When Israelites who stood for God were ordered to kill their fellows who had stood for the Golden Calf.

Prayers for the Departed

The two disparate texts intoned at Ariel Sharon’s funeral tell us much about contemporary Jewish attitudes toward life, death, and the land of Israel.

One of the Most Spectacular Songs of Praise in the Jewish Liturgy

Nishmat starts with the wide-open sky and the wings of eagles; it ends deep inside the recesses of the body, in our vital organs.

The Murder-Ballad of Abraham and Isaac

Can you imagine the person who bathed you and put you to bed at night tying you up one day and holding a knife to your throat?

The Siddur Is a Battlefield

The ancient priesthood, the Pharisees, the kabbalists, the Ḥasidim—each of these and more have made a stand in the prayer book for what they think Judaism should be.

For the Torah, Women Aren't Commodities, and Marriage Isn't a Pro-Forma Prelude to Sex

The point of the Torah’s rules on foreign brides and divorce.

One of the Most Profound Paradigm Shifts in Jewish History

A biblical story marks the moment when Judaism turned from charismatic authority to institutional authority, and from the rule of judgment to the rule of law.

Why the Generation that Left Egypt Was Kept in the Desert

They looked inside themselves and saw only their own fear, not the confidence needed to make the land of Israel their own.

For Every Material Punishment, A Spiritual One, Too

Read enough of the Hebrew Bible and you could come to the conclusion that the two are intertwined, or even interdependent.

Why the High Priest Is Not Allowed to Mourn

He is dehumanized, his life circumscribed by the need to achieve perfect purity and be a vessel for the forgiveness of the people’s sins.

Praising the Lord on Israel's Independence Day: Yes or No?

The answer comes down to the nature of deliverance, and to what you think the Jewish state represents.

The Silencing of Prophecy and the Rise of Oral Law

The book of Malachi, read on the Sabbath before Passover, marks the moment in Jewish history when priestly authority gave way to rabbinic judgment.

The Anxieties of Purim

The book of Esther and the festival of Purim mark the beginnings of the exilic world, in which the battle to remain Jewish never really goes away.

The Most Boring Torah Portion of the Year?

Vayakhel records in painstaking detail the making of the tabernacle. It also makes clear one crucial truth: the central task of Jewish leadership is not atonement but teaching.

The Ominous Undertones in the Bible's Description of the Temple

Solomon builds it for the Lord, but the Lord is not so impressed.

Why Moses Resists Being Chosen to Lead the Israelites

He insists he’s not cut out for the job, and his reason has something to do with the way he speaks.

The Crucial Contrast Between Joseph and Moses

Moses acts, while Joseph sees himself as being acted upon.

The Final Reverberations of Sarah's Life

How her fear and her mistreatment of Hagar the Egyptian helped forge the descendants of Abraham into a people, in a forge of 400 years.

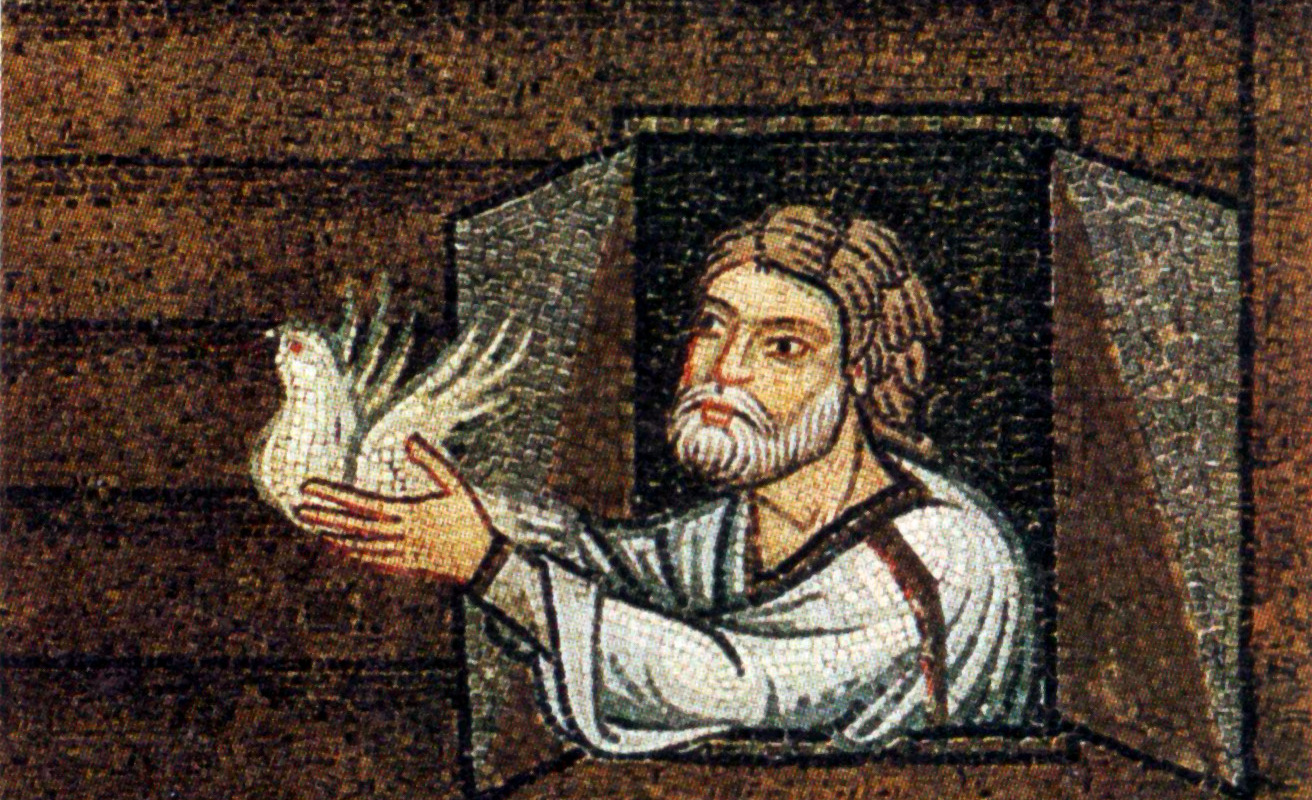

Why Doesn't the Jewish Tradition Hold Noah in Higher Esteem?

Abraham and Moses are considered wholly righteous men, but Noah isn’t quite. That’s because, unlike them, he does what he’s told without question.

The Personal Prayer at the Heart of the High Holy Days

“Here am I, poor in deeds,” it begins. Where did it come from and, more importantly, what does it say to us?

How Moses Let Go

For 40 years, Moses held tight to the Jews lest they relapse into idol worship. As his time drew to an end, he forced himself to loosen the reins.

Were Reuben and Gad Right to Ask Moses for Land on the Other Side of the Jordan?

Wherever Jews live, God lives within them.

Mutiny in the Bible

What happens when the people rebel against the leadership of Moses and Aaron?

Did It Really Happen, or Was It a Dream?

God ordered the prophet Hosea to marry a whore and father her children. The rabbis can’t decide if the story actually happened or was purely symbolic.

Why Israel's Memorial Day Turns into Its Independence Day

And why this week’s Torah portion fits into the spirit of both days.

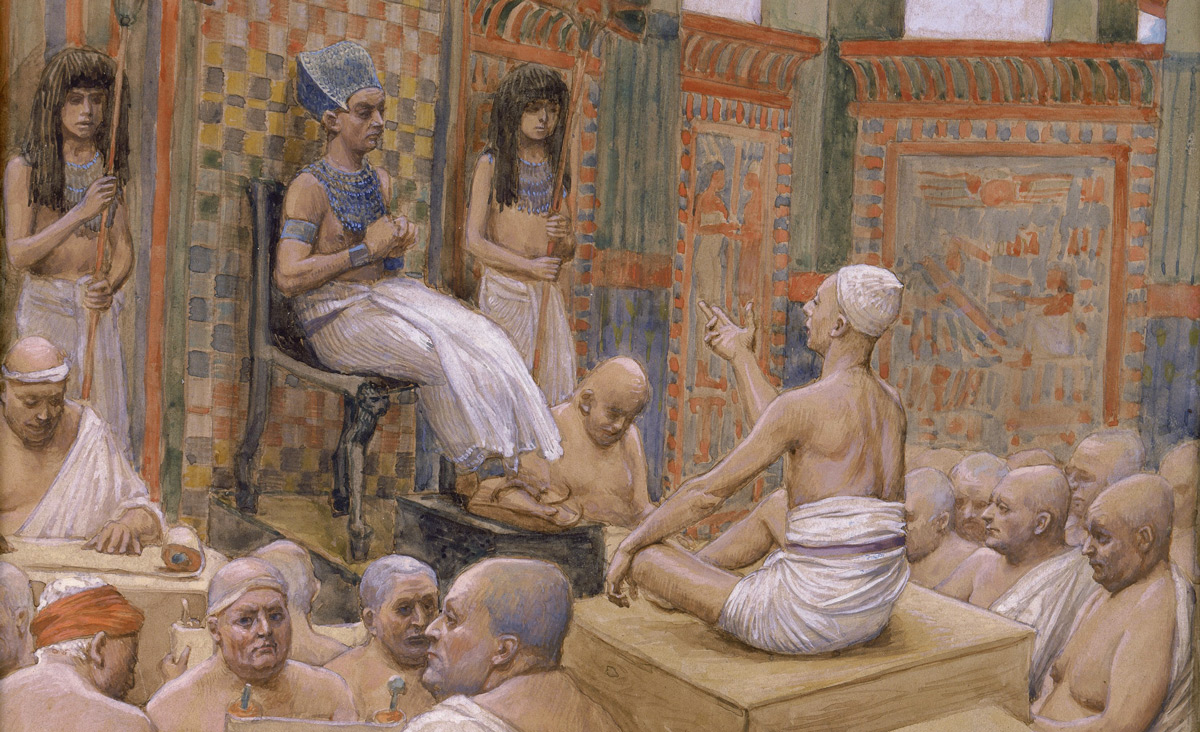

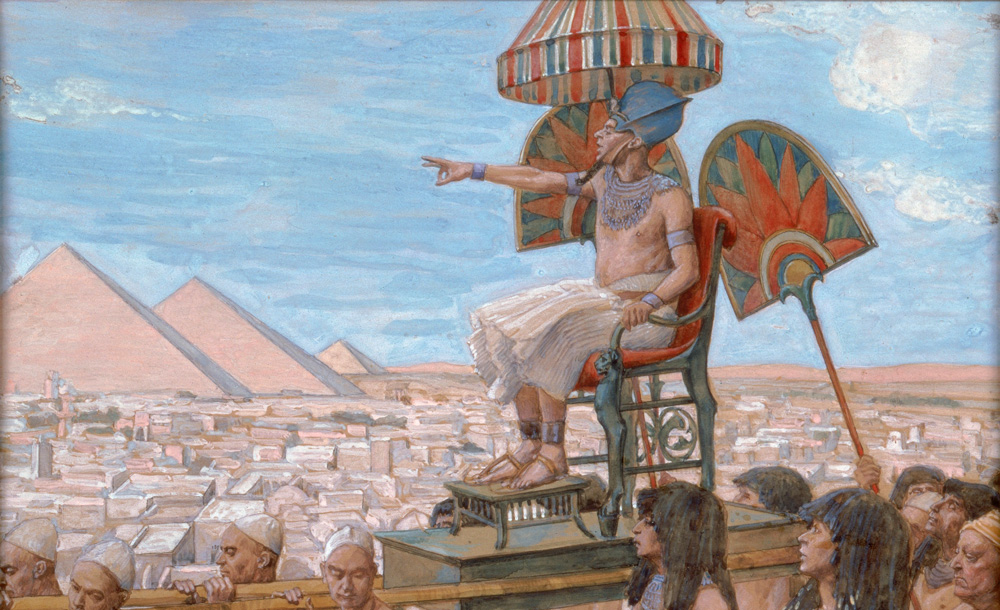

The Bible’s More Than Three-Dimensional Pharaoh

You can hear the man’s voice as he keeps changing his mind. What’s the point of such a Shakespearean portrayal?

What to Do When the Lord Orders Vengeance

God wanted all of Amalek dead. Saul thought he knew better. What happened next?

A Woman Who Fired the Torches

Why Jewish girls are named after the fierce prophetess Deborah.

Do We Learn Only through Terrible Pain?

It’s hard to read the story of Joseph and his brothers without asking that question.

Jacob, the Innocent Con Artist

Was Jacob born to greatness, did he achieve it, or did he have it thrust upon him by his mother?

The Most Complicated Character in the Bible

It isn’t Moses, despite the four books devoted to his adventures—it’s Abraham. Why?

Guilty, Guilty, Guilty

Why should we confess, particularly on Yom Kippur? Why in public? And why so many times?