Walter Laqueur’s thesis, stated in the first sentence of his incisive essay in Mosaic, is both disturbing and indisputable: “Turbulent times tend to produce turbulent voices.” As Laqueur also points out, such voices can lead to horrendous behavior on the part of ruthless politicians and their followers. As a prime example, he cites the case of Hitler’s Germany, where the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was distributed in millions of copies and where Jews were systematically subjected to unprecedented humiliation and violence. What is more, he writes, even in democracies like the United States, public figures in diverse walks of life have gained substantial followings by adopting the slogans of the most extreme anti-Semites.

Here I propose to focus not on the German case but on an earlier one that happens to fit within my own area of study: namely, Russia at the turn of the 20th century. There, too, the Jewish question loomed large as widespread turbulence—sparked or aggravated by the earliest edition of the Protocols—brought terrible consequences to Jews in numerous regions of the Russian empire.

Beginning in January 1905, Russia endured revolutionary turmoil so extensive that in 1920 Vladimir Lenin would claim that without the “dress rehearsal” of 1905, it “would have been impossible” for his Bolshevik party to seize power in 1917.

Lenin exaggerated: actually, World War I, a catastrophe for Russia, created the conditions that made the Bolshevik revolution possible. But it is certainly true that for much of 1905 the country was in such deep political disarray as to bring into doubt the survival of many vital state institutions. Otherwise disparate groups—middle-class liberals, surprising numbers of nobles, industrial workers, factory owners, peasants, and some national minorities—turned against what they regarded as the source responsible for the chaos: the autocratic regime of Tsar Nicholas II.

In October 1905, following about ten months of anti-government protests and numerous incidents of unrest, a general strike by industrial workers proceeded to paralyze much of the country. Nicholas, having up till now hesitated to act, finally agreed to major concessions, issuing a manifesto that granted certain civil liberties—including freedom of conscience, speech, and assembly—and promised that in the future no measure would become law without the approval of an elected state parliament (Duma).

Although the outcome was, despite the usual label, not a true revolution—the tsar did not relinquish political power to the people—neither was Nicholas any longer the sole repository of power. By agreeing to something he had vowed never to do—namely, abandon the principle of autocracy—he had brought about a fundamental change in the Russian system of rule.

Reaction was not slow to materialize. In response to Nicholas’s capitulations, the attention of some turned to locating and punishing the “villains” who had allegedly brought the tsarist regime to its knees. The villains named were the Jews, who then numbered a mere five million or so out of a population of roughly 130 million and who had long endured numerous forms of deprivation and discrimination: confined for the most part to the Pale of Settlement in the empire’s western and southwestern provinces; permitted to travel to other regions only by special permit; subjected to taxes not imposed on other ethnic or religious groups; obliged to serve in the armed forces but without any possibility of promotion to officer rank; and proscribed from employment in the civil service. With rigid quotas restricting their entry into universities, only a small portion of Jews could hope to gain a higher education.

This, then, was the small, beleaguered minority against which, in late October or early November 1905, a new political party rallied the people. Known as the Union for the Russian People (URP), the party advocated not only undoing the political concessions reluctantly granted by the tsar and restoring the autocracy but also punishing the alleged fomenters of the unrest. Of the roughly 200 right-wing organizations established during this period, the URP became the largest and most influential.

About the social composition of the party, not much can be said with certainty; apparently, it attracted the support mainly of the degraded and widely looked-down-upon sectors of the working class (the Lumpenproletariat), plus a few disgruntled members of the middle class and a small number of peasants and ordinary workers.

Nor is much known about the early career of Alexander I. Dubrovin, the party’s leader, other than that he was a medical doctor who despised Jews even though, according to one source, many of his patients were Jewish. (It was also rumored that he had been in intimate relations with several Jewish women and had fathered a few children with them.) Once politics became Dubrovin’s primary avocation, he adopted an uncompromisingly racist stand toward Jews; he would not accept any into his party even if converted to Russian Orthodoxy.

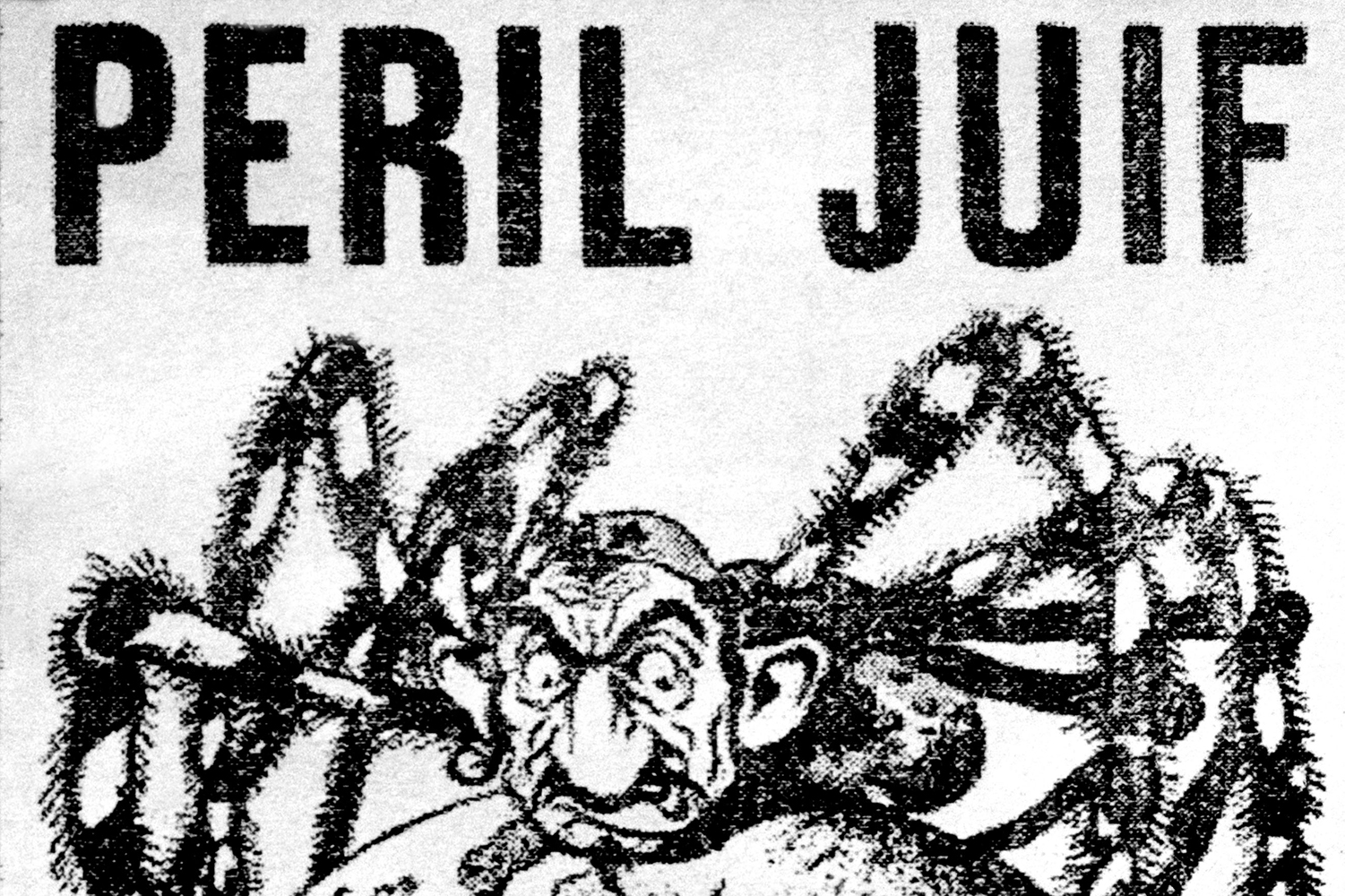

What we do know is that Dubrovin and his colleagues were deeply influenced by the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which had been introduced to Russia in either 1903 or 1905, as well as by a fiery standalone extract from it known as “The Rabbi’s Speech,” purportedly delivered at the conclusion of a secret meeting of the Elders “at whose climax,” as Laqueur writes, “the assembled conspirators proclaim[ed] that ‘our domination will take place when all of the world’s gold will be in our hands, for gold is the New Jerusalem.’”

The members of the URP were especially impressed by the Protocols’ evident confirmation that the “elders” of international Jewry were conspiring to seize control both of their country and of Europe through a revolution carried out by Christians. This, according to Dubrovin and his colleagues, was exactly what was happening in Russia. In their view, the ensuing chaos in the empire was bound to become so widespread and so painful that the masses would be eager to hand over power to the Jews, who for their part would not hesitate to assume the country’s leadership. Under the new regime, Judaism would become the only religion that Russian citizens would be allowed to practice.

To avoid this envisioned catastrophe, the URP advised Christians to regard Jews as foreigners who should be encouraged to emigrate to Palestine. As for those who desired to remain in Russia, they should be treated as aliens but without any of the privileges extended to other foreigners. Members of other minorities, who composed over 50 percent of the country’s population, should be “Russified.”

In explaining the need for this policy, one URP spokesman wrote, rather bizarrely:

Can we call a man “Russian” who does not believe in the Church and sacraments; who does not recognize the autocratic tsar; and who wishes that in place of the tsar, God’s anointed Sovereign, there would be deputies as there are now in the city councils . . . Would we not call such a man a Muslim?

Although the URP did not succeed in attracting a mass following, its influence was far from negligible. Late in December 1905, the tsar welcomed Dubrovin and 23 members of his movement at court and paid careful attention to their declarations of loyalty to the autocracy. After accepting two URP badges, he declared his agreement with their aims. “I am accountable,” he said, “for the exercise of my power [only] to God.” When a URP delegate by the name of I. I. Baranov boasted that the party was denying membership to Jews who had converted to Christianity, on the grounds that Jews were responsible for the “present turmoil in Holy Russia,” and on the same grounds urged the tsar not to grant them equal rights, Nicholas replied with five cautious but encouraging words: “I will think about it.”

The URP was not the only organization that propagated anti-Semitism in Russia, but its agitation was an important factor in promoting the frequent pogroms that occurred in the aftermath of the 1905 general strike. According to a reliable Russian newspaper, 690 attacks were perpetrated on Jewish communities, most of them in the southwestern provinces, in the weeks following the work stoppage; 876 Jews were murdered and between 7,000 and 8,000 injured, quite a few seriously. The damage to property owned by Jews has been calculated at 62 million rubles, which in present-day U.S. dollars would amount to about $2 billion.

Also in 1905 and 1906, street demonstrations organized by the URP frquently ended in violence committed by “armed squads” accompanying the marchers. One of the squads’ stated goals was to assassinate prominent leaders of the opposition to the tsarist regime. They succeeded in murdering two leaders of the liberal Constitutional Democratic party, M.I. Herzenstein (a Christian convert from Judaism) and G.B. Gollos. Several URP officials even advocated “mass slaughter” of Jews as a way of solving the “Jewish problem” in Russia.

In Russia, then, the malignant influence of the Protocols on political affairs was fully evident quite some time before the work’s arrival in Germany—where, as Laqueur points out, it appeared at the end of World War I and soon reached the acme of its popularity, becoming, with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, nothing less than (in the historian Norman Cohn’s phrase) the warrant for genocide. As Saul Friedlander, the eminent historian of the Holocaust, has written in Nazi Germany and the Jews:

In Germany, where the Protocols was excerpted in 1919 in the völkisch publication Auf Vorposten, it came to be considered concrete proof of the existence of dark forces responsible for the nation’s defeat [in World War I] and for its postwar revolutionary chaos, humiliation, and bondage at the hands of the victors. Thirty-three editions appeared in the years before [emphasis added] Hitler’s accession to power, and countless others after 1933.

Since that year, we have come to learn that even after the horrors of Nazism, and especially in turbulent times, it is not uncommon for citizens to be taken in by racist slurs directed at Jews by political leaders, even if the consequences can be disastrous for entire nations.

More about: Anti-Semitism, History & Ideas, Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Russia