The last time I hung out with Richard Spencer, back when he presented himself as a movement conservative, back before we knew he was a white supremacist, he and I got in a fight about the Catholic Church.

Spencer and I were at a house party on Capitol Hill full of young conservatives, and some topic of discussion—maybe it was immigration, maybe it was abortion, or maybe euthanasia—spurred Spencer to attack the Catholic Church with vitriol. I had recently come into the Church as an adult, and I defended the institution.

I had been warned by a fellow Catholic that Spencer held some views closer to Peter Singer than to Saint Peter. (“Conservatives try to save dying cultures!” my friend had paraphrased Spencer’s argument. “We should be pushing them off the cliff!”) That was in the Bush years. I was not that surprised, then, when in the Trump era he became the most prominent white supremacist in America. His argument against pro-lifers at this point became more explicit too, calling the pro-life movement “dysgenic.”

Tamara Berens, in her feature on the last decade of right-wing anti-Semitism, notes Spencer’s desire to make the right post-Christian. Spencer, Berens writes, “thought that the substance of the Christian religion itself was no longer needed (even if Christian heritage could be a useful identity marker).” Berens argues that right-wing anti-Semitism has mutated since Spencer’s heyday in 2016. It has become less pagan and more Christian in its presentation, she writes. As the endpoint in this journey, she uses the openly anti-Semitic Nick Fuentes, a self-professed Catholic.

The story Berens tells certainly casts light on today’s anti-Semitism. As a Catholic writer who has written a book that pins many of America’s social pathologies on secularization, my attention is piqued by an article that discusses Christianity’s role (including Catholicism’s) in anti-Semitism, especially an article whose writer is clearly not anti-Christian. What I can add to this story is some social science and some of my own reporting. I’ll begin with an answer to a question that appears in Berens’s piece.

Berens illustrates the shift in conservative culture in Washington D.C. over her years with this comparison:

When I first arrived in Washington, the young aspirants I encountered would sometimes ask each other when they had last traveled to Israel. Now the question is “Where were you on January 6th?” And some don’t mean it hoping the answer is “anywhere but the Capitol.”

Where was I on January 6th? I was at the Capitol.

“I’m hoping for a big information drop,” Kurt, a man who I spoke to that day, told me before President Trump spoke. “Today is supposed to be the day when we get some information.” January 6, in the Christian calendar, is the Epiphany. On this day, we remember the visit of the Magi to Baby Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, as the moment Christ’s divinity was revealed.

Many of the men and women in D.C. January 6, 2021, were seeking some sort of revelation. They simply didn’t believe Trump had lost. They believed in something like a vast conspiracy that had swallowed up even Fox News, Mike Pence, and the Republican government of Georgia. “There’s so much disinformation out there, you don’t know what to believe,” Kurt lamented.

So how did Kurt ever figure out what to believe? “I do my own research,” he told me. This turned out to be as much about faith and spirituality as it was about recounts and the news media.

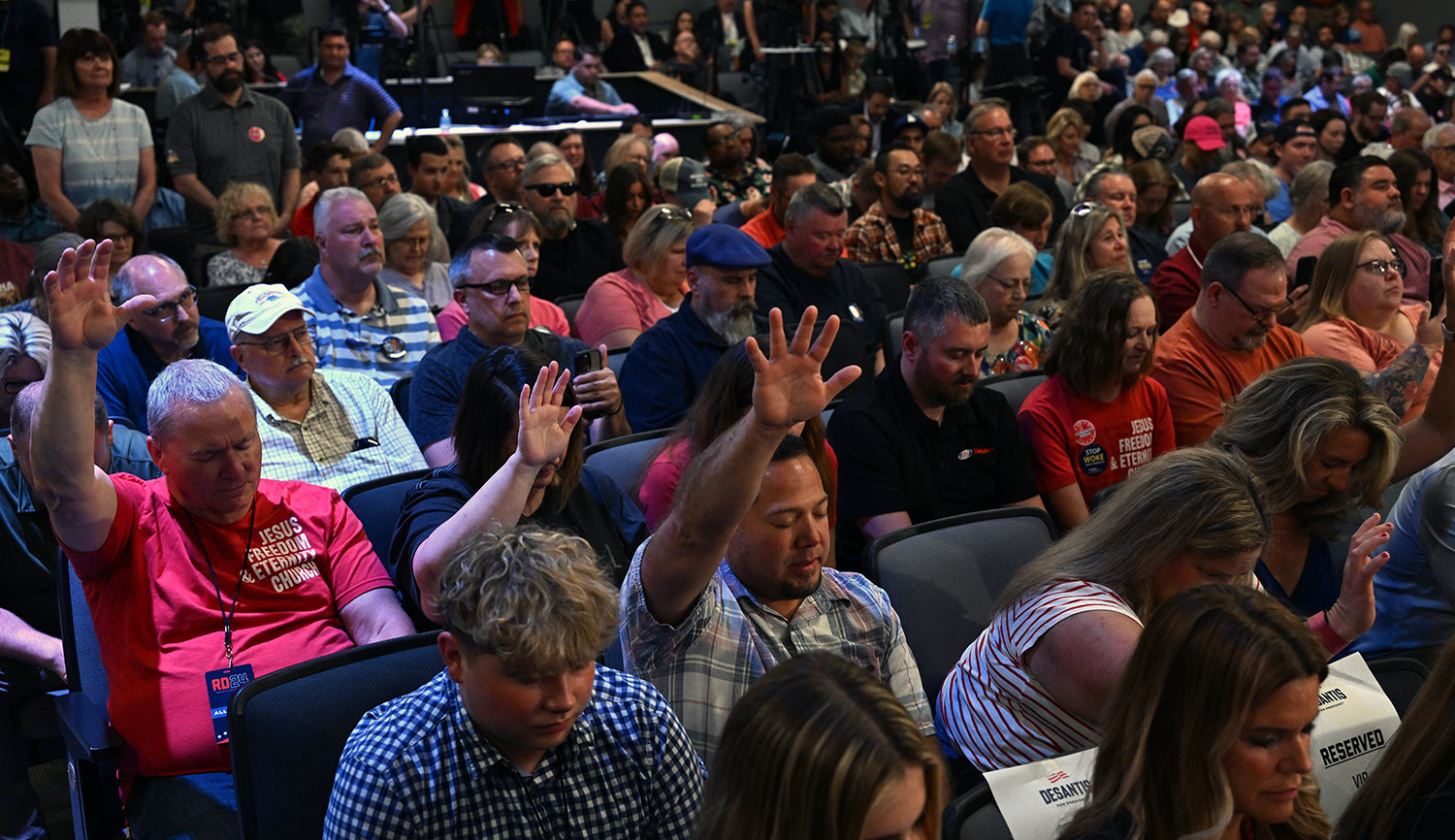

Throughout the day—outside the White House, on the walk to the Capitol, and then on the Capitol grounds—I asked the protestors what they believed, both about the election and about God, the universe, and everything. Of those who identified as Christians I asked, “where do you go to church?”

“I don’t go to church,” said David, an auto mechanic from Colorado. “But I am religious. I do read the Bible. I do my own studies, online and stuff.” Ronnie, from Ocala, Florida, who lamented that nobody would ever know the truth about the election or anything, told me, “Honestly, I just read the Bible.” An Alabama family, who spoke at length about the importance of their faith, told me they also don’t go to church.

Indeed, churchlessness was the rule among those I met marching to the Capitol on January 6. In a paper called “No Money, No Honey, No Church,” the sociologist Brad Wilcox says it’s becoming the norm in working-class Christendom. “Religious life among the moderately educated is becoming increasingly deinstitutionalized, much as working class economic and family life have become increasingly deinstitutionalized.”

So if you’re looking for the roots of rising anti-Semitism and other conspiracy theorizing among conservative Christians, you should probably look at the unchurching of white Americans. The chief example Berens cited of anti-Semitism by a relatively mainstream Christian conservative was Republican congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene. Greene’s history with churches is telling. She was baptized and married in the Catholic Church, which she has since left. “Satan is controlling the church,” she has said on television.

Then she got “rebaptized”—meaning she believes the Catholic Church is not actually Christian—in a Georgia megachurch called North Point Community Church. She seems to have left this church, too—and perhaps all churches. When a left-leaning Christian group looked for a spiritual leader who might have sway over her, the best they could find is the pastor at North Point, whom they identify as her “former pastor.”

Unchurched white conservatives like the ones I’ve been talking about have a very particular cultural bent. Pew Research polled Americans this year on their feelings towards particular religious groups. The pollsters also asked respondents to describe their own religion. The good news from the Pew survey was that basically every religious group expressed net positive opinion of Jews. The groups with the least positive opinions of Jews were atheists, followed by a group who called their religion “nothing in particular”—sometimes referred to as “nones.” Catholics, Protestants, and Muslims are all more philo-Semitic than are the irreligious, this survey suggests.

A far more comprehensive study turned up a more meaningful finding. The Democracy Fund is a polling outfit that convened a project called the Voter Study Group around the time of the 2016 election. The pollsters asked a wide range of probing questions of voters, and sorted through the responses until they found a handful of meaningful clusters. Trump’s core support came from a group that the Democracy Fund’s Emily Ekins labeled the “preservationists.” This group, inspired by Trump’s motto Make America Great Again, revealed themselves in poll questions to “feel powerless against moneyed interested and the politically connected and tend to distrust other people,” as Ekins put it.

The distrust was deep. The preservationists were “the most likely to believe that most people look out just for themselves rather than try to help others (62 percent) and will try to take advantage if they get the chance (66 percent).” This is the sort of person in whom conspiracy theories and scapegoating most easily take root. This, in other words, is fertile territory for anti-Semitism.

Here was the most important part of Ekins’s analysis of the preservationist cohort: “Despite being the most likely group to say that religion is ‘very important’ to them, they are the least likely to attend church regularly.”

There’s more information to support the connection between the unchurched and anti-Semitism. A few years later, the Democracy Fund revisited the Voter Study Group and asked Trump voters for their feelings towards certain groups. They found more of the same: attendance correlated with trust and toleration. Specifically, one question asked “on a scale of 0 to 100 where 0 indicates a very cold feeling, and 100 indicates a very warm feeling, how do you feel about Jews?” Among Trump voters who went to church at least once a week, 84 percent had warm or very warm feelings towards Jews. Among those who never went to church, it was significantly lower: 69 percent. This reflected the pattern on attitudes towards immigrants, racial minorities, and tolerance of others in general: more frequent church attendance means more tolerance of other groups.

The Democracy Fund ran a regression analysis, to calculate how much of that attendance-tolerance correlation persisted if you controlled for education, race, age, and income. They found “greater church attendance significantly predicts more favorable attitudes toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, and Muslims even when taking into account the effects of other variables.”

Again this suggests a real link between right-wing anti-Semitism and never going to church.

With no offense to my friends or readers in the clergy, it is not likely the preaching on “love thy neighbor” that makes churchgoers much more tolerant of others.

Religious attendance likely works on our hearts much how most institutions of civil society do, just with more power. At church, synagogue, or mosque, we meet lots of people whom we find we can trust. Their differences from us—in age, race, income, background—subtly implants in our hearts the idea that people very different from us can be trusted. That habit of trust soon extends beyond those with whom we would pray on our respective sabbaths.

Belonging also acts as an inoculation against conspiracy theorizing. The great 20th-century Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton aptly wrote that the madman isn’t mostly guilty of illogic but rather of an inhuman hyper-logic. The most common conspiracy theories are as illogical as they are unlikely.

Something about belonging, trusting, and reciprocity grounds us in the real. Isolation leaves us to the devices of our own minds, in which logic and imagination replace reason and wisdom. The Democracy Fund’s polls hint at this. On the question of whether most people can be trusted, the least trusting were the “never attend” group, and the most trusting were the “weekly+” group. The same pattern held on the question “would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful or that they are mostly just looking out for themselves.” The only groups of Trump voters in which a majority said “mostly just looking out for themselves” were the never-attenders and rarely attenders.

So, yes, institutions of civil society can foment hatred, of course preachers can preach conspiracy theories and anti-Semitism, and sure, Nick Fuentes calls himself a Catholic (evil has always found a way to sneak into the Church). Our best bet to fight far-right anti-Semitism is to seek out what works the best over time. That means our best hope is to pray that our unchurched countrymen return to the pews.

More about: America, Anti-Semitism, Christianity, Far right, Politics & Current Affairs