I would like to thank Tara Isabella Burton and Tim Carney for their insightful responses to my essay, and Samuel Goldman, Douglas Murray, and Jonathan Silver for taking the time to discuss it with me live on June 29. Taking their thoughts into consideration, I’d first like to dilate on an important distinction with regards to the prominence of Christian nationalism on the far right, then move on to broader questions, and finally say something about the historical antecedents to the situation I’ve outlined.

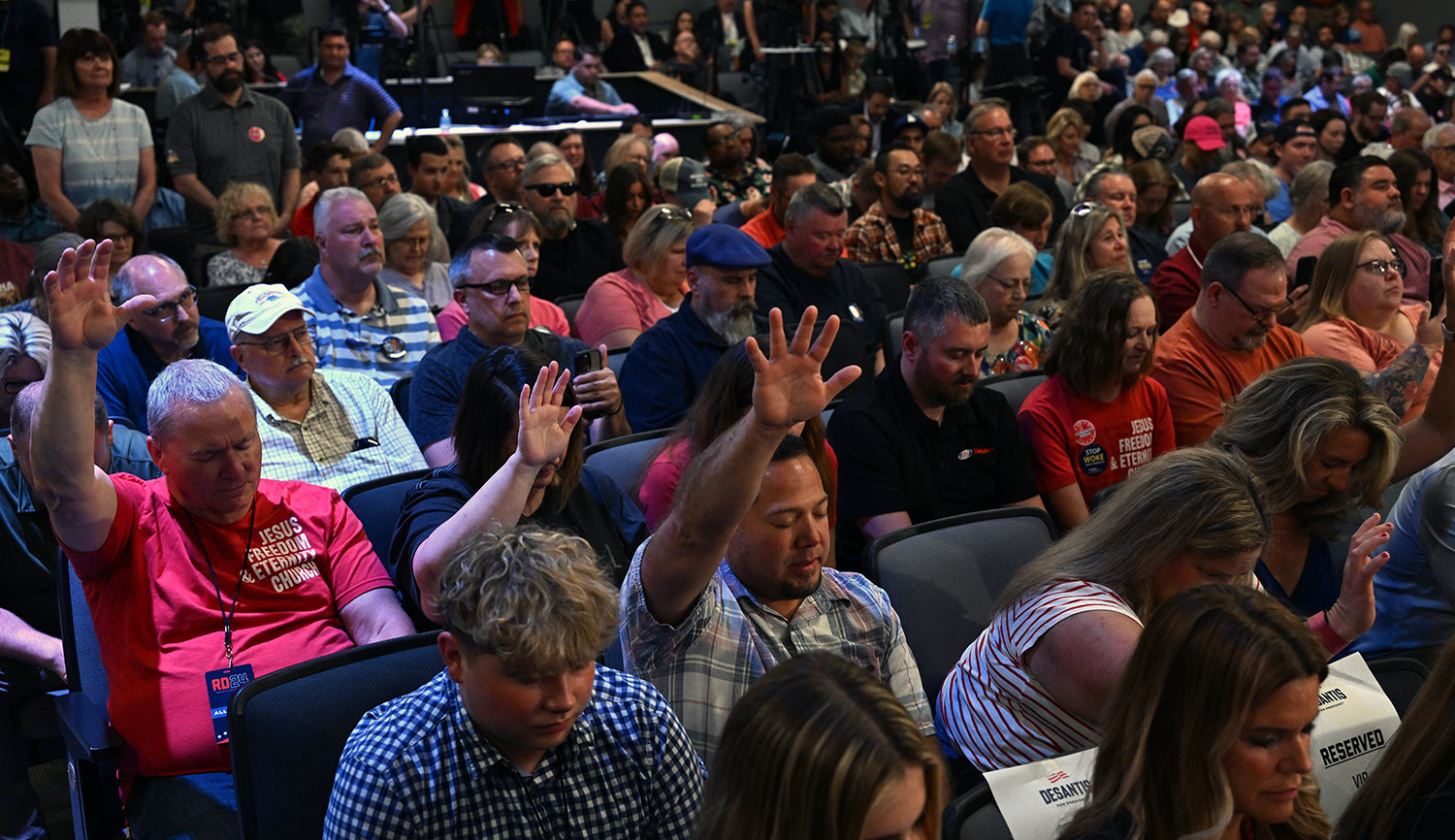

I argue in “From Coy to Goy” that, whereas the alt-right of 2016 exhibited an eclectic mix of pagan disdain for Christian morals and white supremacy, the far-right of 2023 is (at least overtly) more Christian-nationalist in its flavor. That particular articulation of political Christianity seems, as Tim Carney argues, not an expression of, but instead a departure from, much of organized congregational Christianity in America. The unchurched appear to have more in common with post-Christian ideas than with more traditional forms of religious devotion.

In yesterday’s conversation, we talked about the political messaging used by some self-described members of the Christian right. In Goldman’s estimation—which accords with Carney’s empirical findings—the anti-Jewish approach of the Catholic, anti-Semitic Internet personality Nick Fuentes is out of step with the considerably more philo-Semitic attitudes of those American Christians who identify as both religious and conservative. Goldman noted that in the history of Christian nationalism, particularly in Europe, “Christian” means “not Jewish.” And it remains to be seen how the altogether different historical and political traditions of American democracy will recast that European tradition in a more ecumenical form. But most concerning would be the growth of a version of Christian nationalism that indeed is a euphemism for a political order that excludes the Jews.

My essay seeks to explain that anti-Semitism on the right in America is a problem that conservatives shouldn’t ignore. The conversation and responses to my essay all point to the further question of what caused anti-Semitism’s appearance in this form. My interlocutors have all provided partial answers: Burton points to broad social and cultural trends, and the anxieties they produce; Carney to the rise of the unchurched Christian; Goldman to an ideological turn against liberal modernity; and Murray to the failures of older conservatives to impose guardrails on the younger members of their movement. These explanations complement rather than contradict one another, and I can only urge those who haven’t yet done so to read or listen to these remarks.

And that leads us to the most consequential unanswered question: how should the right respond? In seeking an answer, I recommend looking to some of the historical precedents for our current situation, and to what distinguishes the current situation from its precursors.

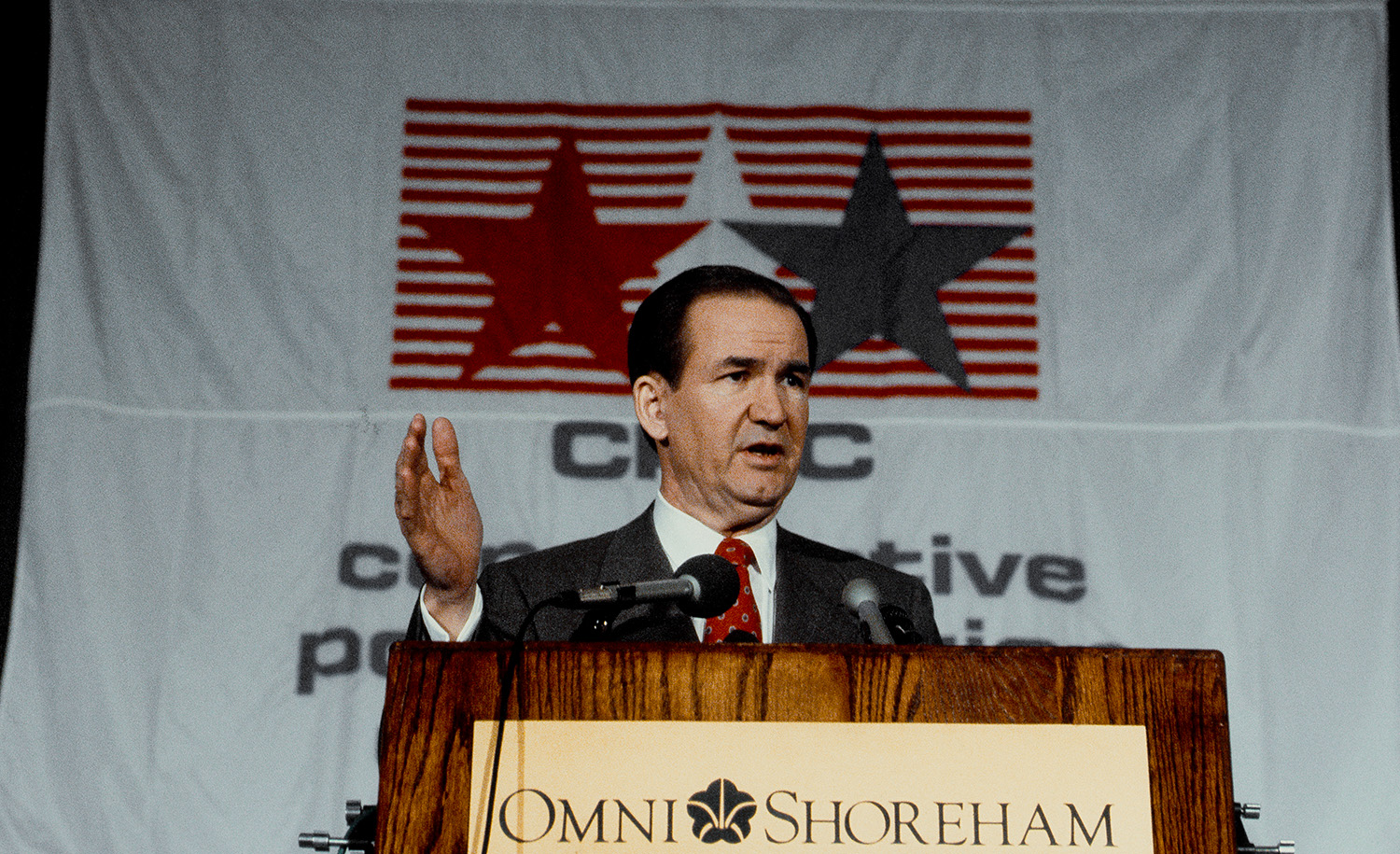

In the 1960s and again in the 1990s, William F. Buckley, Jr. drew clear red lines over anti-Semitism, first with the John Birch Society, and later with the former Reagan staffer and then-popular media personality Patrick Buchanan and with National Review’s own columnist, Joe Sobran. The dispute over whether Patrick Buchanan’s comments about American Jews and Israel constituted anti-Semitism sparked a lively debate in 1992, the same year he challenged George H.W. Bush for the Republican presidential nomination.

Commentary issued the harshest rebuke from the right, marking perhaps the highest profile break by Jewish conservatives with a mainstream Republican politician since the magazine’s emergence as a Jewish voice on the right in the 1970s. The story begins with a column by A.M. Rosenthal in the New York Times, arguing that Buchanan’s criticism of U.S. involvement in the Gulf War relied heavily on anti-Semitism. Rosenthal pointed to one statement in particular: “There are only two groups that are beating the drums . . . for war in the Middle East—the Israeli Defense Ministry and its amen corner in the United States.”

The piece ignited a storm of responses. The definitive one, in my mind, is Joshua Muravchik’s essay in Commentary. With characteristic thoroughness, Muravchik examines Buchanan’s character, his record on Israel from 1976 onward, his views on the First and Second World Wars and the Holocaust, and much else, and concludes that Buchanan is indeed an anti-Semite by his own definition of term.

Buckley deals with the incident in his 1992 book, In Search of Anti-Semitism, a volume containing his own lengthy essay on the subject, responses to it, and various related correspondence. At the heart of the book is not Buchanan, but Buckley’s erstwhile friend and ally Joe Sobran, who long held the post of senior editor at National Review. Sobran developed an anti-Israel obsession around the time of the Gulf War, but also more plainly attacked Judaism itself.

It’s striking how similar Sobran’s efforts to defend himself are to those now frequently heard from left-wing anti-Semites: he insists that he isn’t a bigot, but simply a critic of Israel, and that his enemies are trying to stymy debate about the U.S.-Israel relationship by branding such criticism anti-Semitism.

In his rebuttal, Buckley carefully constructs a useful distinction between personal and political anti-Semitism. Sobran and Buchanan might be motivated by personal animus towards Jews. But that question is far less important than the political implications of their actions, which are clear. As public figures, Buckley argues, they have high standards to uphold, perhaps especially in their treatment of the Jews, who do require special care, given the recent evils of the Holocaust. Buchanan and Sobran’s statements, at times careless, and at others, seemingly calculated, indicate a dangerous abdication of these standards.

Like Muravchik, Buckley observed that the support for the Gulf War by such prominent Jews as Charles Krauthammer and Henry Kissinger was entirely in character with their general attitudes towards foreign policy, and therefore can’t be attributed to nefarious Jewish special pleading. In contrast, Buchanan’s apparent support for the intifada and his derision of Israel goes against his general policy attitudes. (What other left-wing, Soviet-backed revolutionary movements did Buchanan support?) Buckley in the end broke with both Buchanan and Sobran over their anti-Semitism.

What lessons, if any, can be learned from this history? First, that these irruptions from the anti-Semitic fringe happen periodically. Second, that much depends on the ability and willingness of intellectual, media, and political authorities—the adults in the room—to maintain guardrails and red lines. The advent of the Internet and social media makes this much harder to do. And, the adults have had a fairly spotty record in recent years. That’s not reason to despair. Anti-Semitism on the American right has been restrained in the past, and summoning the spirit to do so again begins by recognizing its recurring presence.

More about: Anti-Semitism, Politics & Current Affairs