For years, Mosaic has devoted its attention to addressing the urgent problem of anti-Semitism on the left in America and across the world. This month, it has turned its gaze toward the same problem on the political right. In “From Coy to Goy,” the writer Tamara Berens finds that over the last several years, a constellation of far-right activists has grown and united into movement bent on challenging the American conservative tradition and the Republican mainstream; and Holocaust denial, Jew-hatred, and opposition to the U.S.-Israel relationship are all central to its identity.

To delve more into Berens’s essay and explore the battle over anti-Semitism now being waged on the American right, Mosaic has invited the prolific author and journalist Douglas Murray to join Berens and the political science professor Samuel Goldman for a conversation.

Watch

Read

Jonathan Silver: My name’s Jonathan Silver, I’m the editor of Mosaic. Welcome to this afternoon’s discussion with Tamara Berens, the author of our June essay, “From Coy to Goy,” which explores strains of anti-Semitism on the right.

Tamara and I are joined by two distinguished guests, the George Washington University political scientist, Samuel Goldman, and the author and journalist, Douglas Murray. Let me say a word about what we’re doing and why.

Mosaic was established in June 2013. This month, we celebrate ten years of publishing essays on Jewish letters, Jewish culture, Zionist history, Israeli politics and national security, and the biblical and religious foundations of Jewish civilization. In the course of these last ten years, we’ve published dozens of essays on the subject of anti-Semitism, its origins, and its penchant for modulating itself to harmonize with the dominant chords of the culture. In some eras, anti-Semitism deploys theological arguments. In some eras, it is presented as a consequence of biological science. At times, anti-Semitism manifests itself in utopian incantations about human rights. For the past decade, we’ve published work that focuses on the outgrowth of anti-Semitism from the political left, looking at its Soviet and Communist inflections, and also at the nodes in Western life where anti-Semitism has been incubated in the universities in prestige and legacy media and also in social media.

This month, we decided to turn our vision in another direction. In a moment, I’m going to ask Tamara to recapitulate the main themes of her essay and then we’ll hear from Douglas Murray, author most recently of the War on the West, and then from Samuel Goldman, author of After Nationalism.

For those of you who are joining us live, I want to especially thank you for being part of our subscriber community. We simply could not publish work like this or convene conversations of this kind without your support.

Tamara, why did you write “From Coy to Goy”? What’s this essay about?

Tamara Berens: Thank you so much, Jon. First I’ll just say what a privilege to be sitting here with Douglas Murray and Sam Goldman. Douglas was really the first writer who made me think, “I want to do this. I want to engage with ideas in the public square.” Sam Goldman was the first teacher that really got me thinking about conservatism as a series of often conflicting ideas rather than just a set of policy positions. So thank you both for being here.

I’ll start by summarizing the arguments I made in my piece, “From Coy to Goy,” for everyone watching and listening who might not have read it in full. The piece at its core examines the nature of contemporary right-wing anti-Semitism in America and the extent to which it influences mainstream culture and on a closer level, conservative and Republican institutions, which aren’t always the same thing.

The story begins at the time of the 2016 presidential election cycle and the rise of what was then the alt-right, or the alternative right. There was a convergence of factors that led to this, beginning with the reliance on social media for news, and then candidate Trump’s reliance and use of social media himself. Groups of extreme people and institutions that were formally on the fringes began looking to Trump as a popular vessel for their ideas. And there was a huge spike in online anti-Semitism targeting prominent Jews like Ben Shapiro.

Of course, the Charlottesville Unite the Rights riots followed, and then the catastrophic Pittsburgh synagogue shooting and events like this. At this time, the anti-Semitism voiced on the right was distinctly white-nationalist in flavor, and it was also quite peripheral. It was seen as incidental to Republicans success. It certainly was not the key force driving Trump’s ascendance and anti-Semitic individuals themselves were not mainstream.

They were also mostly coy about their anti-Semitism. If anything, it was something that they were sort of caught out on, but they were trying to hide. Someone like Milo Yiannopoulos then of Breitbart would play into this publicly a little bit, but he would sort of issue this coy approval for these anti-Semitic online memes shared in the 2016 election, kind of laughing the thing off, not directly declaring his stance on that front. And in general, the whole thing was sort of treated as a bit of a joke.

How could something so online and so absurd like memes about a frog, which is one of the core memes of 2016, how could that have any political impact? The piece argues that today’s far right is much more successful and entrenched, not yet ascendant, not yet front and center, but getting there much more so than the alt-right of seven years ago.

It’s also no longer necessarily alternative because it’s much more attuned to and in proximity to the mainstream than we would like it to be. There are lots of reasons for this, which I go into in the piece, but I’ll just focus on three areas for now.

The first is that anti-Semitism on the far right has shifted away from white-nationalist symbols and towards a more publicly palatable Christian nationalism. To be clear, this is a complete perversion of Christianity and I think it’s well worth reading the written responses to my piece from Tara Isabella Burton and Tim Carney, which deal with this. But these people aren’t actually religious. Nonetheless, they pretend to be and they adopt Christian nationalist symbols, however distorted and hollow.

And this is significant because I think it resonates much more strongly with a larger audience who are kind of attuned to the culture wars and who see this sort of thing as more acceptable than, let’s say, the kind of arguments that one would hear about immigration and white nationalism in 2016.

Those seemed like symptoms of a broader disease in American society, but they didn’t offer an all-encompassing worldview. People weren’t really taken by these kind of pagan and folksy symbols espoused by the likes of the white nationalist Richard Spencer. Whereas with this Christian nationalism, which we see espoused by people who are really far off to the fringe, like Nicholas Fuentes, who is a young live streamer mostly appearing from his basement who’s nonetheless fomented a lot of nonsense. He has recently been working with Kanye West and of course, whether he was invited or not, he spent time with Trump at Mar-a-Lago.

He espouses this sort of argument. So do people who actually have a stake in political power like Marjorie Taylor Greene, who toys with anti-Semitism and is openly Christian nationalist and paints a vision of a Christian nationalism that’s under siege by an internal enemy.

I think that’s quite a powerful message. To that end, there’s a second trend that I want to discuss as mentioned in the piece, which is that people like Nick Fuentes are much less coy about anti-Semitism than the alt-right of 2016. That goes to the title of the piece “From Coy to Goy,” these people really identify as goyim. The core of their motivations is their belief that the Jewish people are kind of a fifth column within American society. They’re undermining American values, but not only America, they’re undermining the conservative movement specifically.

There’s this idea that Jews have sort of subverted the movement from within, forcing people to support Israel when really there’s no logical reason for the U.S.-Israel relationship, and so on and so forth. And so of course someone like Kanye West has come to symbolize the popularity and normalization of anti-Semitism and he has acolytes around him, Fuentes being one of them, the other one being Milo Yiannopoulos, who’s always kind of falling in and out with Kanye West. And Yiannopoulos himself has taken on much more overtly this kind of anti-Semitism that in 2016 he was more coy about. And he himself actually identified as a Jew at the time, but now he identifies as a Catholic.

I’d say a third issue that I’ll mention is this seductiveness of breaking the barriers of free speech and how much that has become associated with speaking out against the Jews. Free speech is an incredibly important value to me. It’s built into the American republic, but there’s this sense on this kind of extreme shadowy area of the far right, influencing the right increasingly, that there are certain things that you can’t say about Jews and Israel and that this is kind of the next frontier in safeguarding free speech.

We’ve seen actually Candace Owens talk about this with regards to the ADL (the Anti-Defamation League), basically asserting that it has formed a lobby with Zionists to prevent people from speaking out about things that they believe in. And it’s interesting to see Owens aligning herself with people who are adjacent to the Black Lives Matter movement and the Black Hebrew Israelites, when that was something that she was originally vehemently against.

We’ve seen this with Joe Rogan as well, who’s popular on both right and left. He argued that the idea that Jews aren’t into money is ridiculous—that it’s like saying that Italians aren’t into pizza, which I think is very worrying.

What does all of this mean? One of the arguments that I make about the broader political implications of this is that I could see this virulent anti-Semitism perhaps being weaponized on the right for political purposes, just as we see on the left, for example, in the UK with the rise of Jeremy Corbyn, which I wrote about at the time.

I don’t think it’s happened yet, but I do think that we’re getting closer. Obviously, there are guardrails against this. The United States is philo-Semitic in nature, and I think that kind of undergirds so much of American life. But at the same time, there’s this political utility to anti-Semitism that’s coming out more and more. And so I’ll just mention a recent example that I know we’ve all been following.

For those watching who might not have heard of Pedro Gonzalez, he’s a very online person and editor at Chronicles magazine. He recently was written about in Breitbart, of all of places, and a series of messages that he had sent in private group chats was sort of gone through in great depth detailing a lot of really vile anti-Semitic statements that he had made, saying things like, “Yeah. Not every Jew is problematic. But the sad fact is that most are.” Talking about how Fuentes, whom I mentioned earlier, is the future and saying that he does good things when he trolls the Jews.

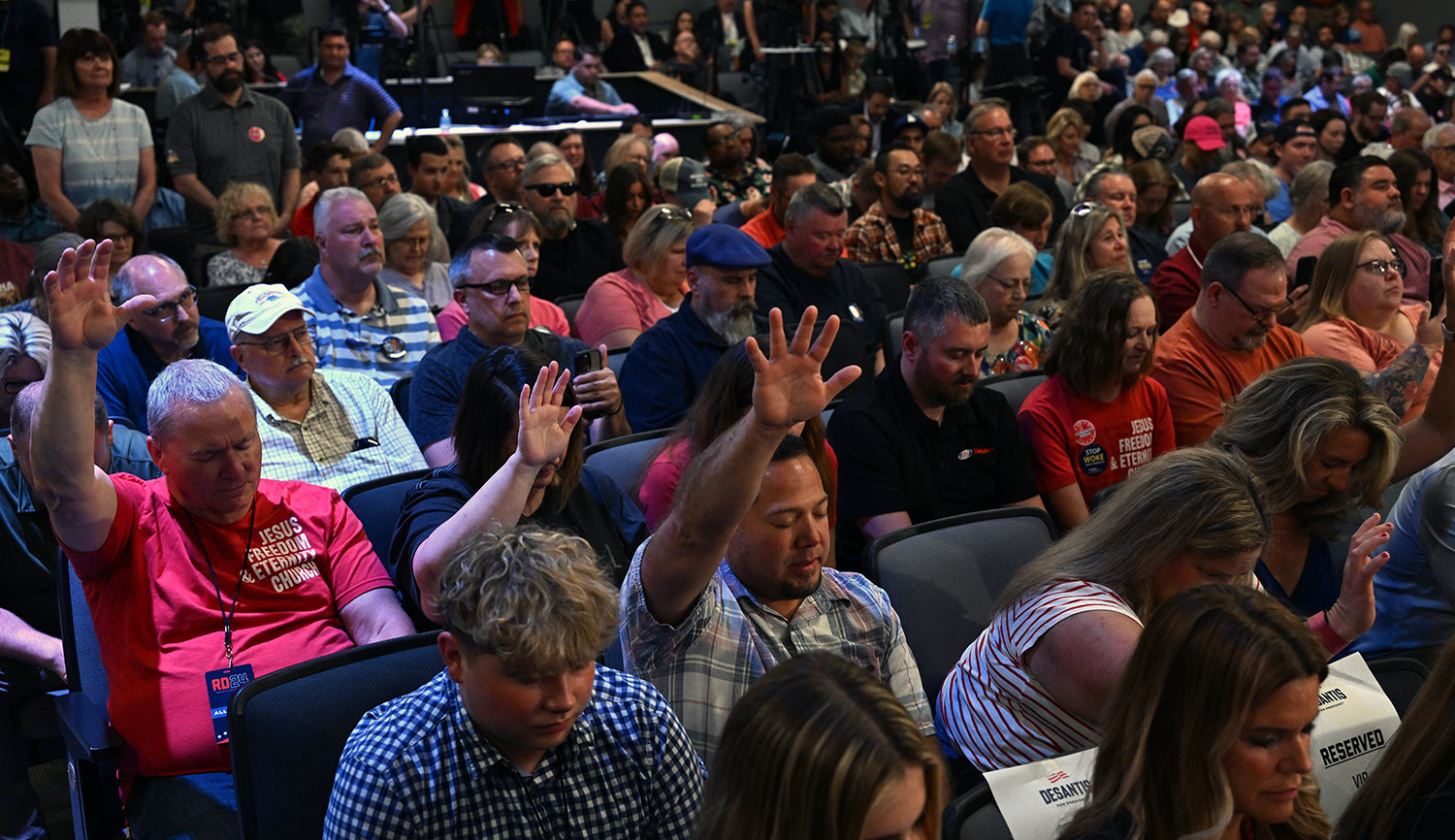

But it’s important to note that the piece is really designed to paint the DeSantis campaign as senseless anti-Semites and it seeks to exonerate Trump, whom Breitbart supports, from this charge. So it argues that Pedro Gonzalez, the person in question, as he’s moved away from Trump, he’s moved closer to anti-Semitism and closer to DeSantis. There’s so much that could be read into this, but the article does actively seek also to exonerate Trump from the meeting with Nick Fuentes and sort of asserts that essentially DeSantis’s response to the messages has been inadequate, even though I think it’s evident that the two can’t really be equated.

So I think this is one of the first examples that we’ve seen after my piece was published in Mosaic of this playing out very starkly in the public square: anti-Semitism being used as a political football. And ultimately the people that stand to lose the most from this are the Jews.

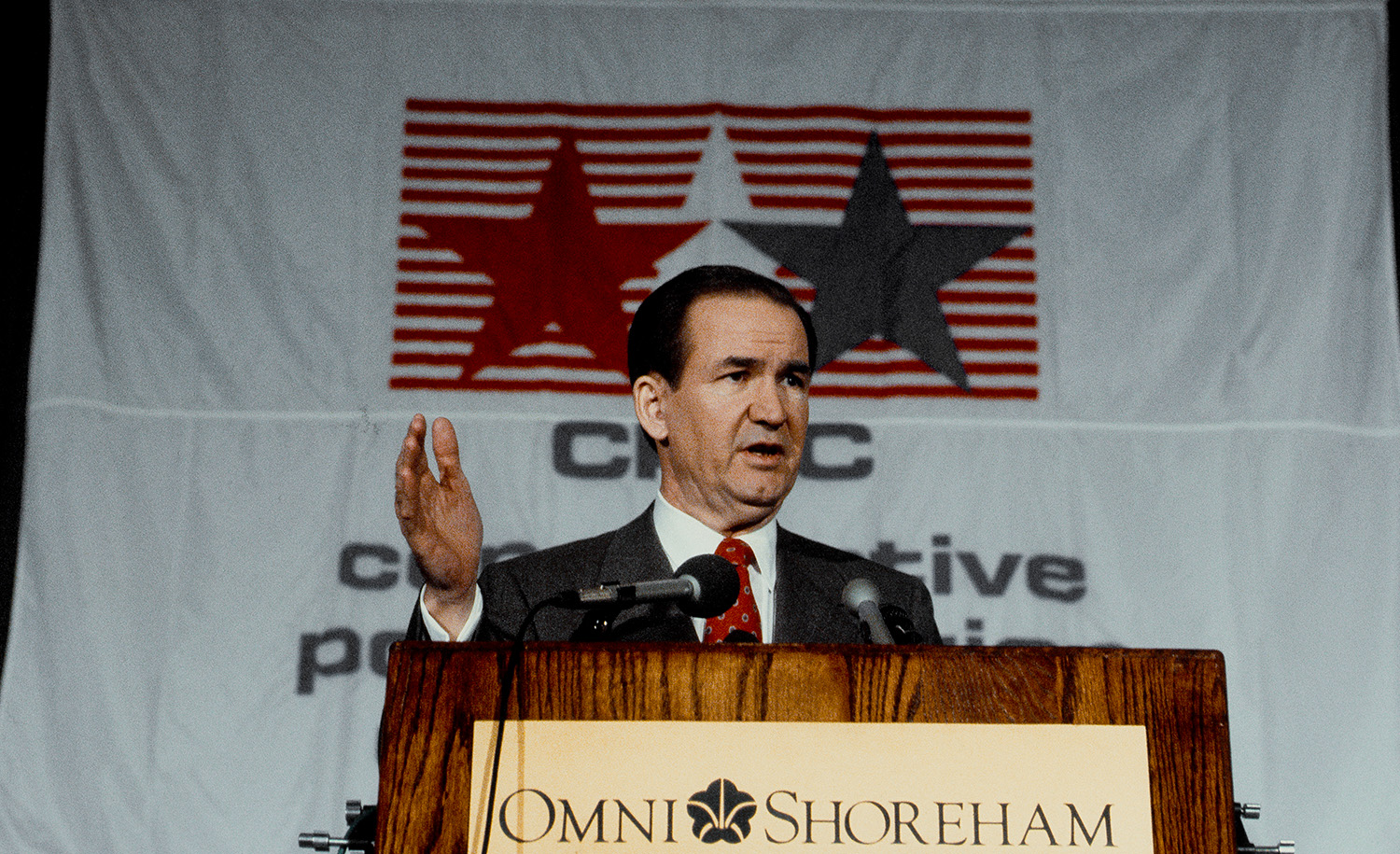

I think it’s very worrisome. Just to sum up, because I’d love to hear from Douglas and Sam as to what they think of all of this, I think that there’s a lot more to be done exposing some of these noxious figures and trying to figure out where exactly they fit within the right and the conservative mainstream. Obviously William F. Buckley Jr., one of the kind of heroic figures on the right, historically took a very strong stance against anti-Semitism within its midst.

He set the lines not only with the John Birch Society, but later with Pat Buchanan and with his own columnist Joe Sobran, really examining at length the way that their positions on Israel and statements that they’d said about Jews veered into anti-Semitism. But I think the standard that he’s set no longer applies either because people aren’t listening to it or it’s outdated and it needs to be updated. And so there’s a lot to be done in this area and I’m glad that we were able to publish this essay and I look forward to hearing what both of you think.

Jonathan Silver: Tamara, thank you. Douglas, what do you make of all this?

Douglas Murray: Thanks very much, Tamara. Just to start where we started from as it were, I think it’s important to stress or to re-stress, although obviously anti-Semitism is played with and is more problematic to many of our minds on the political left these days. The cordon sanitaire is not as strongly held on the left as it has been on the political right in recent years.

But of course it can come from any direction, as I wrote recently. Anyone who knows Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate understands there’s a good reason why Grossman almost exactly at the dead center of the novel devotes three pages to the subject of anti-Semitism. Because as he says there, it’s this shape-shifter which you can meet in the marketplace or the academy.

For our purposes, it seems to me necessary to address it on the political right because it’s important to try to keep your own stable clean. You can endlessly lament other people’s inability to share your views. But if they’re from the opposing political side, it’s not surprising they might not share your views. Whereas of course if there are people in your own stable who are espousing ugly sentiments, I think it behooves anyone to address that.

I should say by the way, there’s a difference between addressing that and cancel culture. There’s been a thing in recent days in particular of saying, you’re engaging in cancel culture if you call out ugly attitudes on your own side. I vehemently disagree with that claim. Everything is not cancel culture. Criticism of people is not cancel culture. But let me just say a couple of other things.

Firstly, Tamara is completely right to say that the William F. Buckley-vs.-John Birch sort of model is simply not doable today. The reason, I would say, is because there is just no similar central figure—whether one would wish for there to be one or not is another matter—strong enough in the conservative movement in America to make any such call or to draw any such line and for that line to be agreed upon. Much of what is in your essay is in part a reflection of that: people are eyeing up where the opportunities are because they recognize that the adults have sort of lost their authority.

There is no figure who would tell them they’re effectively excommunicated from a movement even if such a movement existed. Let me just say very quickly that the left and the right also have obviously different undertones in anti-Semitism. When people on the left stumble into anti-Semitism—let me put it that way to give the most benevolent interpretation—it tends to be driven by their instincts on things like privilege.

They go into it wittingly or unwittingly, and then they start to try to eye up who is privileged in society. Before you know it, they’re identifying the Jews as privileged and the hierarchy. You mentioned Jeremy Corbyn. One of the most famous things that Corbyn did was supported a mural in East London that was virulently anti-Semitic. If he didn’t know, it’s because his brain has been in this water for such a long time that he couldn’t notice it anyway. But the version of that on the political right that I believe has similar traction is in which we’ve talked about before, the bit where you could see actually some progress of anti-Semitism on the American right would be to do with the state of Israel.

Again, actually to go back to Grossman’s point, this is, as we all know, everyone here knows, I’m sure everyone watching know,s the great irony of anti-Semitism being that you can attack the Jews for being privileged or for being poor or for being stateless or for having a state. In the 21st century, Israel and the Jews having a state is going to be on the right of a galvanizing issue. And you see this on the online culture, as you know. It is why the Jews can have a state and have immigration controls and so many prominent Jews in America and in Europe don’t argue for similar controls in other countries.

That is going to be, and you can already see, the place that on the right people are going to move into this area.

I’d just say one other thing, which is that it is an important thing. I mentioned earlier the thing of toying with anti-Semitism. I do think that’s something we’ve probably all become a little bit more aware of in recent years, that there’s a sort of character now in the culture that didn’t, I think, used to exist in the era of newspapers and so on. And that is the so-called edgelord, the person who enjoys toying with dangerous things—you’ve mentioned Milo Yiannopoulos. That culture of knowing you are touching the third rail and enjoying the frisson of doing so is a very interesting phenomenon in our day.

It is important to identify where that is very clearly people toying with the ugliest possible ideas. You mentioned Pedro Gonzalez, but I wrote about him a couple of years ago, not because he’s an important figure, by no means a significant figure, but because he was associated with the Claremont Institute at the time and I thought that somebody writing as he did then about people having Rothschild physiognomy was a dead giveaway that even uglier stuff lay beneath.

And so I wasn’t at all surprised to discover in recent days that there was indeed uglier stuff beneath. But it was striking to me that even at such a relatively low level, there was a sort of incursion into a conservative movement and that the adults didn’t seem to be willing to put it down and address it.

In part, I think that is because the adults are terrified that the excitement and the movement is as it were among the young and we don’t quite know how to contain it. That was what Marjorie Taylor Greene said when she turned up to Fuentes event was I said, I think her line was just sort of enthusiastic young Americans. It’s almost impossible to be that stupid and still speak, but nevertheless she saw it as a sort of exciting youth movement. Again, this is a failure of the adults, which is why it’s so important to be addressing this today with adults.

Jonathan Silver: Douglas, let me pursue two things that you’ve opened up. One, that there was the possibility in earlier iterations of the conservative movement for figures to play the function of a constable of the limits of the movement.

One possible explanation for why that’s no longer possible is, as you’ve said, they’re thrilled to have the energy of the young before them. The authority has devolved unto them, unto the young. I wonder if you think that technology plays another role or what other explanations you might offer.

National Review is still a conservative magazine, but it competes for clicks in the marketplace of ideas with a zillion other platforms. I wonder what you think explains the inability of adults to provide that same kind of limiting function.

Douglas Murray: I’ll have to be slightly careful because I’m a fellow of the National Review. Personally, I would like it if our institutions had more heft, as it were. It is a recent thing in America and I would put it down to—if I were being honest about this, which I should be—the failure of the adults in the 2000s. I think it’s a devastating thing that the perception, correct or otherwise, is that Republicans failed in foreign policy.

It meant that nobody wanted to hear from the people a generation above. By the time you get to Trump and the—what was it?—100 foreign-policy professionals who signed the letter against him, many of whom I had an argument with at the time. It didn’t have any effect because effectively he could say, “I’m sorry, this is 100 people who led us astray.” I’m afraid that argument has a lot of purchase, this happened after Vietnam as well to some extent: if the adults have seemed to have let you down, you’ve got to go to the kids.

Jonathan Silver: There’s an ambivalence in very online right-wing attitudes toward Israel that you have started to contour for us. The ambivalence I would describe like this: on the one hand, isn’t it fabulous that those Jews are embodying a form of nationalism that is altogether admirable, where the relationship between religious authorities and civic authorities has much to recommend in it, where immigration, as you say, is controlled.

Because after all, it is a state for people and there’s much to marvel at and learn from in that experiment. At the same time, Israel is also a source of criticism. Help us to mention both of those sides of the way Israel’s seen on the right.

Douglas Murray: Mind you, I can’t resist telling a joke. “A Jew, a Black man, a Hispanic gentleman, and a bigot sit on a park bench and somebody touches a lamp and a Genie pops out and says, ‘I’ve been in this lamp for so many years. I’ll give you all whatever you want.’ And he goes and says to the Jewish gentleman, ‘What would you like?’ He says, ‘I would like the Jewish people to be able to return to our ancient homeland to thrive there.’ And bang! It says to the Black gentleman, ‘What would you like?’ ‘I’d like to return to Africa all my people, and for Africa to flourish.’ Bam! He’s gone. The Hispanic gentleman says, ‘I’d like to return to Mexico and I’d like to live there in prosperity with my people.’ Bang! He’s gone. And it’s just the bigot left. And Genie says, ‘What do you want?’ And the bigot says, ‘So the Jews have all gone to Israel, the Blacks have all gone to Africa, and the Hispanics have all gone back home. I’ll have a Diet Coke.'”

A lot of people who play in this, as you say, have this slightly conflicted view about Israel. On the one hand they sort of like it and say, “But why is it only allowed for them?” My view is that this is, again, just an old version of the same thing. The Jews can do nothing right. My other favorite example is Gregor von Rezzori’s story rather luridly titled Confessions of an Anti-Semite, about anti-Semitism in the Hapsburg world.

There’s that great scene in the novel where the young man takes an older Jewish woman he’s dating out on a date and is seen by some friends and it ends up with him climatically slapping her in the restaurant. But it’s because she ends up humiliating him by behaving too much like his friends, like the Gentiles.

He can’t bear it. He can’t bear the fact that everyone can see the Jewish woman is trying to be not Jewish. It is such a brilliant description of that endless conundrum. What is she meant to do? If she’s too Jewish, he’ll hate her. If she tries not to be, he’ll hate her. I think this is the case with these, they’re not thinkers but reactors on the right, when it comes to Israel.

Jonathan Silver: Professor Goldman.

Samuel Goldman: Jews have flourished under broadly liberal political institutions and capitalist economic practices like no other people. As a result, whenever politics turns to fundamental opposition to liberalism, again in a general and institutional sense rather than a narrow philosophical one, and capitalism, anti-Semitism almost inevitably results. Now in the 20th century and especially in the second half of the 20th century, that energy was concentrated on the left and that explains the anti-Semitic tendencies in Communism and a little bit later in Black Power and third-worldist movements.

I think a lot of the work that Mosaic has done is responding to the continuing reverberations of those tendencies on the left. But before the middle of the 20th century and certainly in the 19th century, opposition to liberalism and capitalism were found with equal and sometimes greater intensity on the right.

We haven’t gone all the way back to that yet. But we seem to be departing from the 20th-century division of labor, particularly in the United States, where the right stood for the defense of liberal political institutions and a capitalist economy and the left stood for opposition to those things. As anti-liberalism and anti-capitalism have become more respectable of the right—and even, among younger and more online cohorts, the major source of intellectual and political energy—it’s not surprising that anti-Semitism has followed.

Jonathan Silver: Let me put to you a proposition and see what you make of it. That is a very high-minded way of describing the broad trends that one can observe. But if I were to put to you to try to situate the experience of a member of a very online cohort that is enthused by the transgressive thrill that is received by denying the authority of the elders who led us into Iraq, who are responsible for the financial crisis of 2008, who completely mismanaged the COVID epidemic and much else: it’s simply that liberalism has failed in every respect.

It has produced people who are unhappy, who are not confident in our institutions, who are no longer able to summon the patriotism needed to feel a part of this place and why it’s worthy. That’s all liberalism’s fault. It’s not that I object to it in any large abstract sense, it’s the very people I see in front of me: these conservatives have never conserved anything and so it’s empirical that I should want to turn away from them.

Samuel Goldman: Well, I think that’s probably psychologically accurate and to a certain degree understandable. But I evoke the history because I think the history has lessons for us and the lesson of the last 200 years is that the turn against liberalism and capitalism—and again, I want to emphasize, not just criticism of particular practices or institutions, which is often justified—turns out to be very bad, not only for Jews who end up being blamed for these things, but for everyone.

I think it’s important to avoid what Leo Strauss called the reductio ad Hitlerum, where every bad thing you observe is ultimately Nazism. But I think it’s important to understand that as National Socialism and other revolutionary movements of the right were gathering strength in Germany and elsewhere in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, they were driven as much by what we now call the edgelord tendency as they were by a grand explanation of Jewish power or hatred of Jews as individuals.

This was a way of provoking people, which is exciting and fun. It was a way of tapping into inchoate popular energies and it was a way of making vivid the failures of liberalism and capitalism, which in many cases were real failures.

That did not work when it was pursued by movements of the right, which often began as more high-minded and intellectually aristocratic movements, but turned into the abomination of National Socialism. It didn’t work on the left where Stalinism turned out to be something very different from what intellectual Communists and sympathizers had imagined.

It did not work in the 1960s and 1970s when the revived revolutionary Marxism of the Red Army Faction or the third-world nationalism of Africa and the Arab world, again, turned out to be something very, very different from what intellectuals and students and people who wrote for magazines had hoped and expected that it would be.

I don’t know what the future holds. I am confident that these ideas remain relatively limited to the fringe, but it’s a very, very dangerous game. I think that we would be better recognizing and responding to that danger earlier rather than waiting until it becomes a real problem.

Jonathan Silver: There’s one other thing I want to ask you, returning not to your most recent book, After Nationalism, but to the book before that, God’s Country, which is a study of American attitudes toward Hebraism, Zionism, philo-Semitism, and the like.

One of Tamara’s claims is that we have seen a mutation of this attitude on the right from a kind of pagan-influenced white supremacist presentation to something that is more bound up with Christianity. Now, it seems that you presented a mid-century conservatism, which is an exception and achievement in which the Jews were a part of it and at home but that had parted ways from an earlier conservatism, an earlier movement on the right in which Jews were then too subject to anti-Semitic attitudes.

Something similar might be said for Christianity, which in the American tradition has had both great fondness for the Jews and has also harbored its own anti-Semitism extending quite far back into history.

Samuel Goldman: Well, I think one of the significant developments, and Tamara talks about this in her essay, is the adoption of Christianity or Christian nationalism as a primarily political concept rather than a religious one. My intuition, and I think this is supported by survey and other data, is that among believing and practicing American Christians, including and maybe especially conservative Christians, the feelings toward Jews and Israel are very warm.

That’s a good thing and that’s one of the reasons that I am not yet willing to push the panic button. But over the last few years, Christian has come to function much more as a political and cultural symbol than as an expression of religious belief or activity. When Christianity functions in that way, it’s primary and maybe ultimately it’s only meaning is “not Jewish.”

Forgive me for being pedantic; it’s my privilege as a professor to do that. When you look at European history and the emergence of political movements in the late 19th century that called themselves Christian, they have that in their title, but the meaning of Christian is “not Jewish.” It does not mean membership in a church or other religious community. It does not mean personal faith. It means “not Jewish.” That, I think, is the danger that’s associated with the concept and rhetoric of Christian nationalism.

Jonathan Silver: Tamara, we’ve heard from Douglas and Sam, what do you make of them?

Tamara Berens: Douglas, I was really taken by your point about the adults in the room being absent at such a crucial period of time and the impact that that’s had. And as someone who is younger and who really grew up in that period throughout the Iraq war and the financial crisis, I think that’s very much evident. I can imagine too, that for lot of the people watching and listening, some of these names, these very online personalities—even if you’ve heard of them, you must be wondering how they could they possibly have any influence; or these names are just nonsense to you.

But as someone who occupies this space as a young conservative, it really is all about this constellation of individuals and there’s no one holding the balance of power. In some ways it really mirrors what we’re seeing internationally on a grander level.

I think the experience that I’ve gleaned from working on this essay and just listening to you now is how important it is not only for adults to step in the room, but also for, I think, perhaps some of the courageous kind of younger and more online figures to take a stand on this and just grow up quite frankly.

I don’t think that will happen on its own necessarily. I think it requires institutional strength. It might be contingent on a broader kind of revival in American society of just some of the values around polite discourse that have really been lacking. I don’t know quite what we can do to fix this, but I’ll just say that it is gratifying on the one hand to hear that you don’t feel that it extends that far, that you’re not ready, Sam, as you said, to push the panic button.

But on the other hand, from where I’m sitting, I am sort of closer to pushing that panic button, just by being surrounded by a lot of these noxious personalities who are taking hold as you get younger and lower down the chain. It’s about trying to bridge that gap and trying to find some adults like yourselves who can really perhaps offer some more guidance and occupy a larger space than currently is the case among the young emerging conservatives in and around Washington.

Jonathan Silver: Douglas.

Douglas Murray: Can I add one thing to that? Much of this is going to do with a very precise analysis and diagnosis of where people are actually treading over a certain line. I have to say one of my fears is, and again this would be where an incursion into the mainstream would occur, that there is a breach at the moment because of the over-diagnosis of anti-Semitism and a claim of its existence in places where it is not.

Let me give an example, just from recent days. The comedian Roseanne Barr was recorded saying something that sounded very anti-Semitic and Holocaust-denying in a video clip. If you look at the whole thing, it’s clear that she wasn’t saying what the clip seemed to suggest. Now, the clip went round the world, and I’m not criticizing him, but Ron Lauder issued a statement on behalf of the WJC condemning this.

Now there’s a problem there. A lot of people notice that and don’t like it. It looks like policing of comedians. I don’t think Ron Lauder needs to discuss comedians and what they should and shouldn’t say. There’s too much of that. And that does cause, and I notice it online, it causes a form of resentment. Let me give an example of another kind.

In 2016 or 17, after the election of Trump, there were two Democratic party operatives who took over an organization called the Anne Frank Institute for Mutual Understanding or something like that. They had absolutely no connection to the Frank family and they used this vehicle as a way to attack Donald Trump and accuse him of anti-Semitism. They caused quite a lot of ill-will understandably, because they were just operatives.

Now, I would just say that it is crucial that when people are accused of this, it be done accurately. I know myself, that when people are inaccurately or deliberately for political reasons accused of these things, it itself causes problems.

Samuel Goldman: If I may make a suggestion about where to draw the line, it seems to me that it might be helpful to focus on anti-Semitism as a theory of Jewish power in contradistinction to stereotypes or sort of tasteless humor. Tamara quoted somebody saying, “Jews love money like Italians love pizza.”

Douglas Murray: Joe Rogan.

Samuel Goldman: Yeah, Joe Rogan said that. That’s annoying. I wish he hadn’t said that. It’s not a nice thing to say, but that doesn’t really bother me. More generally, I think one function of Jewish conservatives can be to challenge the response that’s characteristic on the left, which is that the problem is hate, is bigotry, it’s sort of generalized sentiments of dislike which start with bad jokes and end with concentration camps.

I think we can say no to that. The problem is not personal dislike or stereotypes or bad jokes. The problem is a theory of Jewish power. The problem is the idea that Jews are running the world in a way that benefits them and screws you. That’s the idea that is noxious and dangerous and I think does require the drawing of lines. Not bad jokes.

Jonathan Silver: Yes.

Douglas Murray: Absolutely.

Jonathan Silver: The first political question that always has got to be asked is cui bono? “Who benefits?” is the question that I think has got to be applied to accusations of anti-Semitism. It is our great teacher, Ruth Wisse, who has defined it as the organization of politics against the Jews.

It is not the same as individual stereotyping. It has that collective quality. That’s very important. There’s another thing that made me initially hesitant to enter into this territory, which is the imprecision in the language of the left for whom there is no distinction between National Review and Breitbart, for whom it is all the same. Anybody who takes one step over to the conservative side is the same as an alt-right fanatic.

I did not want myself to believe that the sorts of attitudes that we were seeing on the right were there precisely because I’d heard so often that they had existed, that they were the animating impulse of the center right. And it’s precisely because of that imprecision that I myself was initially hesitant to enter into these grounds.

Tamara, you’ve mentioned this several times, your position as a person who yourself is in touch with very online members of the right who at least mute their criticism of anti-Semitism or indulge it in some sense. Maybe you could just tell us some of your own experiences that led you to want to write the essay to begin with.

Tamara Berens: I’m glad that you asked that, Jon. I think it was something that I’d sort of suppressed because I was very much in the mode of criticizing the left and left-wing anti-Semitism, especially coming from the UK where I grew up and seeing the dominance of Corbyn’s Labor party and the manner in which it took power so aggressively. And that’s what I always had focused on.

It was in evaluating my experiences really after being asked to work on this essay that I began to realize just the extent of the emerging associations between Jews and Israel on the right that were so worrisome to me. I think Kanye West in particular was the person who so surprised me in terms of the reaction to him or the lack of reaction to him that I experienced from friends.

Someone like Kanye West is so obviously, to me, just a terrible human being in every respect and has very little or nothing to offer the right. And so having conversations with friends who perhaps sought to redeem him from his worst comments and sort of look upon him with optimism that he might change or that he just needed a bit of handling, he needed better PR, that to me just seemed absolutely absurd. I think that was sort of when I started examining whether I was really operating from the same kind of first principles as some of these people.

I just want to respond briefly to what Sam was bringing out with regards to Joe Rogan because I do think that there is a danger and Douglas, you’ve said this as well, in over-policing the right and picking out statements and comments that really are not anti-Semitic because of the boy-who-cried-wolf problem.

But I think what I’ve seen with both Kanye West and also I would argue that this applies to Rogan’s statement, not to him as a whole, but to what he was doing in that moment, specifically with the Jews and money comments: there’s this idea that you can’t say anything about the Jews, and that’s really what Rogan was saying.

He wasn’t himself saying, “Jews like money, ha-ha, like Italians like pizza.” But he was lamenting this thing that he’s noticed in our discourse where he believes that you can no longer make jokes about Jews. What I find funny about that is that it’s sort of similar to how people responded to Kanye West. And it seems so evidently false to me that you can’t make jokes about Jews. Jews make jokes about themselves all the time, were so late to talk about our own downfalls.

We never talk about the Holocaust or the state of Israel, really. We don’t. We allow people often to make jokes about these things and this idea that the Jews have so much power that no one can say anything about us. This is obviously what Kanye West picked up on in all these ridiculous claims about his management. It’s just false to me. I think it’s that kind of false analysis that is very disturbing to me because you’re sort of entering into a plane of just total surrealism with regards to the position of the Jews in society. Again, it’s this out-sized perception of Jewish power. I wish we had that much power, but we just don’t.

Douglas Murray: There is a difference, isn’t there? Jews tell jokes about Jews is obviously. . . . Most of the famous comedians in the world are Jews. It that’s a different thing from, as it were, a non-Jew being allowed to make jokes about Jews, which is I think is a cordon sanitaire that does effectively operate. It’s recognized that most minorities are allowed to joke about themselves. You’re not allowed to joke about them.

You’re allowed to use language about your own group that you can’t use about another group. And obviously American society in particular is fused with that. Again, that stuff doesn’t worry me so much. Humor is a subject of itself. I like Clive James’s definition, that humor and common sense are the same thing going at different speeds and the humor is common sense dancing. The thing just to return to it though, which is much, much more difficult, is the conversation I think the right should be able to have and should have out and goes back to these serious questions that exist, which do provoke the sort of, “We’re not allowed to talk about the Jews,” stuff.

Yoram Hazony and many others have observed this and are trying to do their own thing about it. But if it is the case that people will notice if the Jewish state exists and nationalism isn’t okay for anyone else, there is going to be a bubbling recognition of that. There are other versions of that. I said after my book, The Strange Death of Europe, some years ago, I said that one example that made me just hold my head in my hands at this stupidity of everybody involved when a number of African migrants illegally entered into Israel.

Israel recognized that they were illegals, wanted to deport them. There was a significant international outcry about this. Israel was totally within its rights to enforce its own border policy. In the end, the EU volunteered to take the migrants and you just think, what better way to create anti-Semitism on the right. That’s how you would do it. Actually, it goes back to your point of, and this is a crucial one in Europe and in America, what is the non-hyphenated American? What in a diverse society in Europe is the person who does not have a diverse bone in his body, as it were, and has no place on the intersectional hierarchy pyramid?

Those people who are a majority have to be able to answer those questions and discuss those questions. There’s a sort of right-wing fear of that debate as if we’re not able to have it. I think we can have it.

Jonathan Silver: My friends, I’d like to invite your questions. While you’re typing your questions, let me just ask a question about this business about Kanye. Nobody’s really claiming seriously that Kanye is a conservative or a player in the conservative movement or anything like that. I think just to pick this apart a bit, it’s that Kanye’s comments were then defended by conservatives. The question I would pose is why were they defended by conservatives? Were they defended by conservatives because of the free-speech issue or because of the anti-Semitism that he gave permission to come out and they had wanted to surface in some sense? Do you think that anti-Semitism is the reason for the conservative defense of Kanye?

Tamara Berens: That’s a big question. I’ll just say briefly, I don’t think it’s the reason for the conservative defensive Kanye by any means, but I think having a blind spot on anti-Semitism is very telling and it’s just not what you would expect of a conservative movement that has so traditionally welcomed Jews with opened arms and included prominent Jews among not only its higher ranks, but in terms of actually shaping the movement. But I’d be curious what—

Douglas Murray: I have a very straightforward explanation for this. I’m not an expert on the work or thought of Kanye West. I’m not sure he is either, but let me just say very obviously what happened there.

Conservatives were enormously flattered at a star of his star-wattage being anywhere near their orbit. Conservatives are used to not being the cool kid in the class. When one of the biggest celebrities on the planet seems to be available to your side, you’re enormously flattered. It’s the best date in town and it’s only happened a couple of times in our lifetimes.

That was the biggest one. That was the biggest potential crossover of a megawatt celebrity onto the conservative side. The people who threw themselves in with him who were just so flattered that he was in our orbit then, when he amazingly enough turns out not to be politically reliable, are left stranded. Some of them tried to defend him because they just couldn’t give up the shiny new toy they had. Trump had the same thing with him.

Jonathan Silver: Here’s a question: “How does a philo-Semitic American Christian community distinguish itself in the public square from an articulation of the right that has both co-opted and camouflaged itself with the symbols of Christianity?”

Samuel Goldman: Well, it’s not for me to tell Christians what they should do as Christians, but I think the good news is that it’s not so very difficult to distinguish these symbolic and political invocations of Christianity or Christian identity from genuinely religious ones.

One of the things that has characterized a American Christianity, particularly in recent decades that I think is a healthy phenomenon is genuine interest in Israel and Judaism as a part of the Christian story.

That’s not something that is so easy to fake or conceal. I don’t think that Christians who are genuinely inspired by religious beliefs are in such great danger of being confused. The problem seems to emerge again primarily in an online or online-adjacent milieu of people who are using, sometimes literally, memes of crusaders and so on.

But that’s the extent of their religious involvement. Again, there may be cases of overlap, but I don’t think it’s so very challenging to see the difference.

Jonathan Silver: Sam, I have no evidence whatsoever from what I’m about to say, but I would postulate that when we are speaking about the very online articulation of this fascination with the Jews in such a negative way, I suspect that many of the people that we’re talking about are first of all not part of a recognized Christian community. That was obviously Tim Carney’s contribution to this discussion, that there’s a distinction to be made between the churched and unchurched Christians of the country.

I’d further speculate again on the basis of no evidence, but my hunch would be that many of these people, primarily young men, are not married and don’t have families. And that once they’re bound up in forms of communal life, that make obligations and responsibilities on their shoulders, I suspect a lot of this goes away. I don’t have any evidence for that, but that’d be my guess.

Samuel Goldman: Well, I think, and I also have no evidence for this, but I’ll make a suggestion anyway, part of what’s going on is the de-bourgeoisification of the right and the erosion of those sort of personal and communal and institutional affiliations and replacement by a much more amorphous set of people who are angry and disconnected.

Once again, it is not a surprise, unfortunately, to find that people in that situation find anti-Semitism appealing—and this goes to Douglas’s point that there’s a certain envy mixed in—not least of all because by comparison, Jews now and in the past have seemed to have it together in a way that is admirable but can also seem shaming or dishonest. Why do they have these things when I don’t and I can’t?

Douglas Murray: By the way, to do my bit for Grossman’s royalties again, but just to quote exactly the quote I wanted to give you, he says, and it goes to what you were just saying, in Life and Fate, “Anti-Semitism is a measure of the contradictions yet to be resolved. It is a mirror for the failings of individuals, social structures, and state systems. Tell me what you accuse the Jews of and I’ll tell you what you are guilty of.” It goes exactly to this.

Jonathan Silver: Here’s an anonymous question. “How much of the attitude that we’re now trying to analyze has to do with the fact that most of the Jews that these people meet, that they see, that they read about, are progressives and it’s actually a complaint about progressivism?”

Tamara Berens: I would just pause at that. I think it has to do with that, just seeing the extent to which we’re starting to have these attacks on conservative Jews really emerge. The likes of Ben Shapiro, really no one would say that he’s a progressive. He’s done so much to combat progressivism, rightfully so.

But I think there’s this real sense that people like Ben Shapiro appear to have it together. He has a beautiful family. He’s created an excellent business empire. There’s this sense that they are a perverse force within the conservative movement and that entails not only turning on them as Jews, but I think it also would entail turning on the state of Israel too.

You’re starting to see this, I would say creeping in, and we’ve discussed this a little bit, but I would say I think it has little to do in this case with progressivism. That’s my view.

Douglas Murray: I disagree. I think it’s got quite a lot to do with that. But both political sides can play it as you say. The right can identify Jews on the right, whom they disagree with and see it as being a Jewish thing. They can identify Jews on the left they disagree with and identify as Jewish thing.

However, I come back to this point I made several times. There are on certain issues, particularly on the immigration and integration issues, there are specifically very loud Jewish voices who keep coming up. The most obvious one is George Soros who just will keep coming up. And some of the people who bring him up will do so because they are anti-Semites and they love playing with that. But others are legitimately saying, “You seem to have too much power in paying for open-borders initiatives in countries you don’t live in.”

Samuel Goldman: One thing that I think is relatively new, as Tamara mentions though, is the suggestion, even if it’s not a specific accusation, that Jews have somehow sabotaged intentionally or unintentionally the conservative movement or the American right. This has come out in some of the criticism of Buckley who has been denounced for his famous exclusions, for drawing lines. The suggestion is that if he hadn’t done that, the American conservative movement would have been more successful.

Why did he not do that? Well, it’s because he didn’t want to be accused of anti-Semitism. That in a certain way, to me, seems more dangerous because there are very obvious and clear reasons why anyone right of center might look at Soros and say, “He’s a bad influence. I wish he was unsuccessful.” But to look even at Jews who are active more or less on the right and say that they are subversive, they are seeking personal profit, they may even be intentionally trying to sabotage the conservative movement—that is more threatening, I think.

Douglas Murray: Who was said to do that on the American right out of interest, do you think?

Samuel Goldman: This is why I say it’s a suggestion rather than an accusation, and I think the response should be, well, who exactly did that and what did they do? And I think that’s not an easy question to answer. But the broad suggestion is that in the formation of the American conservative movement after World War II, Jews, many of them ex-Communist, were disproportionately influential and they constructed conservatism around a form of right-liberalism or conservative liberalism based on universal principles that somehow downplayed or even excluded the religious and ethnic core.

The claim, which again is more indicated than argued, is that the American right would have been more successful if it had pursued that form of politics than, again, the more broadly liberal one that it did. I admit that I find this pretty unconvincing. I’m fairly certain that Buckley was closer to the median voter than Revelo Oliver, but that is the critique that seems to be forming in an inchoate way.

Douglas Murray: By the way, again, going back to that thing of accusing others of your own failings, isn’t it fascinating that what Buckley did and what Buckley and Goldwater managed to do was precisely what many of us on the political right have requested the political left do, which is to determine exactly where their side goes wrong and to draw that line. It’s to say, how do you get from progressivism to the Gulag?

The answer is they don’t know because they don’t accept any blame for getting to the Gulag. And so when the right makes that demand of the left and yet says that it shouldn’t do it itself, it’s engaging in such an act of self-harm precisely what one demands on the left and precisely what the right in this crucial intervention of Buckley’s and the Jon Burch Society actually did, which is to say there is contamination on our side. We have to identify it, we have to cut ourselves off from it.

Samuel Goldman: Although the argument then is that this was a form of self-sabotage. The left, ventriloquizing what someone might say, they were successful because they refused to draw lines, because they refused to turn down support where they found it, because they refused to avoid appeals that were fraught but successful. The right did those things and as a result, it lost.

Douglas Murray: Yes. That’s an argument online you come across all the time as it were, we’ve been gentlemanly. They weren’t. Let’s do what they do and give them some of their own medicine. That’s a very popular thing on the young online right, which is we were too polite, we kept our gloves on, they never bothered. Right gloves off, guys.

Samuel Goldman: So if Sharpton and Farrakhan can appear with presidents and attend fundraisers, why should we worry?

Douglas Murray: Yeah.

Jonathan Silver: Here’s a question about Bronze Age Pervert whom Tamara you write about, and you referenced early on that whom we have not discussed.

Douglas Murray: By the way, whenever you mention Bronze Age Pervert, it’s always extraordinary that we discuss and many people watching will think, “What?”

Jonathan Silver: So this question invites us to answer, what do we have to say? What do adults have to say to the 20-year-old who is seduced by the adulation of Nazi ideas that one can find in writing of that kind? It’s not enough to simply say that we disagree with that and it’s wrong and bad. But do we have something to offer in its place that’s more compelling to the 20-year-old watching this conversation?

Tamara Berens: As the person that’s closer to the 20-year-old.

Samuel Goldman: You have to tell us, Tamara.

Tamara Berens: I could try. I’d like to hear what both of you have to say, but I could try. What I would like to hear, I think what we need is a confidence to say, “We are willing to lose if winning means aligning ourselves with the likes of Bronze Age pervert and the likes of Kanye West.” That just goes to the discussion we just had, the conversation among the online right discussing, “Well, wouldn’t the right be better off if Buckley hadn’t drawn these lines?”

It just totally eliminates the moral impetus that most conservatives entered into policy with. If you buy that, which I do, I think there is a record of that, at least for the most part.

So if the goal is just winning, what is winning? Then you’re not really part of a movement. You are perhaps attaching yourself to a cult of personality or to… Then you really veer into something which is so just anathema to what the American republic is about.

Samuel Goldman: So I think I might disagree and invert that argument and say that this is a politics for losers. As I joked a moment ago, I’m pretty sure Buckley was closer to the median voter than Revilo Oliver.

This sort of thing may make you seem tough and transgressive and bold online, but this is not a rhetoric or politics that is going somewhere. On the contrary, as I mentioned, the actual opinion among American Christians and American conservatives towards Jews is quite favorable. If you want to win, which ultimately means winning, if not a literal numerical majority, then at least a working coalitional majority, this is not the way to do it. This is self-marginalizing in a way that is very satisfying to people online and in the past was very satisfying to people writing articles for newsletters and small magazines.

Some instead tried to do what Buckley tried to do, which was to establish and maintain a coalition that could actually win. DeSantis, whatever one’s sort of political inclinations in this cycle are, seems to be interested in doing that. Whatever bottom-feeders on the Internet are saying, you yourself have written Tamara, that Florida under DeSantis has been become a sort of haven for many Jews and as we know, he won election by a large margin. That seems a much more plausible way of winning than saying nasty things in private chats.

Douglas Murray: Yes. What you’re raising goes back to this point of hygiene on the right. It’s a bad sign when people start playing again with things that have already been answered pretty demonstrably.

Jonathan Silver: Every generation has to learn these lessons anew.

Douglas Murray: Yes, but it’s very interesting that there is an energy on the right. Take an example, the integralists in America. They absorb a disproportionate amount of attention on the American right. All of their proposals are preposterous. I still can’t quite believe they’re serious because as I always say, although I didn’t live through the 1500s in Europe, I did hear about them.

The idea that one would revisit the separation of church and state, let alone suggest that the institution of a new monarchy, for instance—fond as I am of constitutional monarchy if you happen to inherit it. Nevertheless, I don’t think it’s a good idea to start one anew. The fact these people are even discussing this seems preposterous to me. I can’t believe they’re serious.

But why do they get the attention? Because there seems to be a lack of thought on the right. And so some people try to go back and they say, “What is it that we are missing?” Maybe it’s that game that always occurs at conservative conferences. Where did it go wrong? Is it 1968? Is it 1789? Is it the enlightenment? Is it the romantics?

This is what a lot of the young conservative inclination people are doing is trying to go and find if there’s something we missed and then they sort of try to read Heidegger and realize that that doesn’t seem to help. And then they do a few other things like that.

This, again, has to be answered by the adults who have to explain, among other things, that this is what the late George Steiner would describe as nostalgia for the absolute. And it has to be explained that part of the nature of conservatism is recognition of the complexity in which you have to live.

Samuel Goldman: I think in that vein, it’s also important to think not only about political strategy, but goals. What are you trying to achieve? If what you are trying to achieve is to overturn modernity, I just don’t think it’s going to happen.

That is not a strategy for winning, that is asking for failure and that doesn’t mean that you have to cherish or accept absolutely everything that has happened until last Tuesday. But not only a successful politics, but I think a meaningfully conservative one has to reconcile at some point with the world that we really live in and that means that we’re not going to return to a pre-Reformation or early modern understanding of the relation between religion and politics.

It also means that America is not going to become an Anglo-Protestant nation again, whatever may have been the case 200 years ago. If conservatism means anything, it means that there is an imperative to grapple with the world that you live in and think about what can actually be achieved in it.

Douglas Murray: Yes. If you want to overturn modernity, you better be very fond of pre-modernity.

Jonathan Silver: My friends, with that, maybe let’s adjourn. Douglas Murray, Samuel Goldman, thank you very much for being our teachers and for joining us. “From Coy to Goy” was published in June 2023 in Mosaic. Tamara, thank you for the essay and thank you for being with us.