Joshua Berman’s “What Is This Thing Called Law?” has much to commend it. As opposed to the rather simplistic declarations typically heard on the subject, Berman offers a serious discussion about what halakhah is, what it should be, who decides it, who decides who decides it, and what role it ought to fill in Israeli and Jewish society—Orthodox and otherwise. In so doing, he draws much-needed attention to the social as well as textual forces that shape halakhic decision-making, and to the conflicts between Orthodox doctrine and the inner life of many committed Jews.

All this is important and illuminating, and I identify with the essay’s overall direction. But in anchoring the discussion in the Bible (Berman’s primary area of expertise), rather than in the Mishnah and Talmud, and in focusing attention on the format of the law rather than its method of interpretation, Berman makes it hard for even a sympathetic reader to be convinced.

The thrust of Berman’s piece is that Jewish law can be divided into two eras. The first, dominated by a “common-law” approach, runs from the Bible until sometime between Moses Maimonides in the 12th century and Joseph Karo’s Shulhan Arukh in the 16th. Thereafter, we enter what he calls the “statutory” era, which endures to the present. Berman argues that the codification of halakhah (somewhat confusingly merged with the “statutory era”) has resulted in a loss of vitality and alienated halakhah from the society it aims to govern. This can be corrected, however, if we recalibrate the dual legacy of “common-law” and “statutory” halakhah to produce a more vibrant and responsive version of the Jewish legal tradition.

Let me begin with the terms common law and statutory law. At least to a modern lawyer, the distinction between the two speaks not, as Berman suggests, to jurisprudential method but to different sources of authority. Where halakhah is concerned, the divide Berman puts his finger on is closer to what legal theorists know as functionalism and/or realism on the one side, formalism and/or positivism on the other.

To oversimplify, functionalism avers that law is a set of policies that the rules aim to embody; to this, the realist adds that law doesn’t simply decide itself, that there is far more maneuverability than most people realize, and that law is open to a host of “non-legal” social considerations. For its part, formalism imagines law as a series of sharply defined rules and categories that are impervious to social influences; to this, the positivist adds that law is nothing but those rules. In other words: one approach sees law as residing within society, while the other reads law as something that acts on society.

Why quibble with terms? Because Berman’s opposition between “common law” and “statutes” is what allows him to spend so large a chunk of his essay describing a legal approach that supposedly stretches from the Bible until well after the Talmud. This is distracting at best. To put it bluntly, the legal reasoning found in the Bible has very little to do with how the Mishnah, the Talmud, or the rest of the halakhic tradition thinks or functions.

Berman is correct that the Bible exhibits few examples of formal legal reasoning. It presents its commandments (mitzvot) within the context of grand theological and national narratives, and asks whether the Jewish nation is living in accordance with God’s will. But this just serves to highlight the differences between the Bible and the Mishnah, whose formalistic or “statutory” framing offers thousands of cases where an individual is either hayav (liable) or patur (exempt); where something is either asur (prohibited) or mutar (permitted); where one has either discharged or failed to discharge an obligation; and so on. These categories are nowhere found in the Bible, but they are the bedrock of halakhic thinking. Hence, the path from the second-century Mishnah to Maimonides’ code (Mishneh Torah) a millennium later, down to the 19th- century code, Mishnah B’rurah, is far more direct than any route from the Bible to the Mishnah.

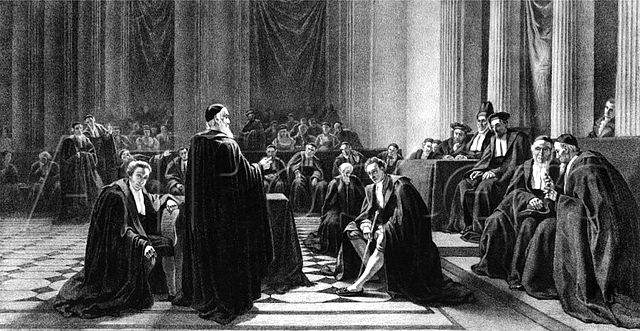

The arguments cited by Berman as examples of the “common law” that allegedly encompasses both the biblical and the talmudic era also have no standing, or parallel, in the Mishnah—or at any point thereafter. His example of Solomon splitting the baby is especially relevant here, though not in the sense he intends. The Bible presents this ruling in the context of a dramatic narrative describing Solomon’s ascendancy to the throne. The point of the story is not the law but the wisdom God grants Solomon to lead the nation.

Contrast this with the opening lines of the Mishnah’s tractate Bava Metzia, which likewise presents a case about dueling claims of ownership. Here the rich tones of the Bible are replaced with prosaic legal phrasing: “Two are holding onto a garment . . . this one says it belongs wholly to me, and that one says it belongs wholly to me. This one shall take an oath. . . .” And legal rule is very much at the heart of the matter. In the Talmud, this passage becomes the focus of a wide-ranging technical discussion about property rights, ownership, and factual doubt, but nowhere is the Solomon story so much as mentioned as a precedent.

I have no doubt Berman knows all this, which makes it hard to understand the basis of his “common-law” tradition stretching from the Bible through the Talmud.

Moving to the other side, Berman also overplays the degree that codification in the Shulhan Arukh creates uniformity or is determinative of halakhic practice. Just glancing at a standard printed page of the Shulhan Arukh shows that subsequent generations had no qualms about undoing its attempts at halakhic tidiness. R. Karo’s words are overwhelmed by commentaries, glosses, and glosses to the glosses. Reading the tiny print reveals that the commentators approach the Shulhan Arukh much as the talmudic rabbis approach the Mishnah.

Indeed, most observant Jews conduct their entire lives with nary a reference to Hoshen Mishpat—the section of the four-part Shulhan Arukh that deals with business and commercial law. The same goes for about half of Even HaEzer (the section dealing with marriage, divorce, and marital property), which could be excised with minimal impact on contemporary practice. Even when it comes to Orah Hayim, the section of the Shulhan Arukh devoted to daily living, many good, God-fearing Jews do not dress in precisely the manner set forth in subsection 2, or insist on having their beds arranged as prescribed by subsection 3, or follow the procedure to have a nightmare “improved” to a positive dream as in subsection 220, or observe a cycle of fast days atoning for excessive levity on Passover and Sukkot as in subsection 492. I could go on.

In the 500 years since it was published, the Shulhan Arukh, like all codes, has been interpreted, molded, and glossed by the society it seeks to govern. To take a somewhat recent example from the American scene, in the 1960s and 70s Rabbi Moshe Feinstein was able to accommodate young Jews returning to the fold even though their parents’ marital status raised numerous halakhic issues. Another example is the worldwide flowering of women’s Torah study in the modern-Orthodox community. Judged by the standard of the black-letter halakhah of the codes, these innovations are highly problematic. But clearly that is not the only standard in play.

Given the many examples of flexible readings of halakhah, what distinguishes today’s situation from eras past? One way of understanding this is to look not only at shifts but at the rhetoric surrounding them. Previously, doctrinal development could have been interpreted as exemplifying functionalism, or halakhah-within-society. Today the discussion has become increasingly self-conscious and formalistic. Moreover, affirming the formalist view that halakhah stands outside society has itself become a central tenet—and boundary marker—of Orthodoxy.

In this connection, we might look at the current crisis over agunot (sing. agunah): women who are civilly divorced and live outside the marital home but, because their husbands refuse to give them a halakhically valid writ of divorce, are prohibited from remarrying under Jewish law. Though it cannot be proven, one senses that talmudic and perhaps medieval rabbis, facing this problem in its modern guise, would have employed their interpretive powers to solve it.

Today, however, though it recognizes the severity of the crisis, mainstream Orthodoxy is committed to the view that halakhah has no tools to fix it. In the United States, the solution has been a pre-nuptial agreement that uses American contract law to export the problem to the secular courts that can do the work halakhah cannot. Notably, the Orthodox women’s organization JOFA, which aligns with Rabbi Daniel Sperber’s conception of Orthodoxy—a model cited by Berman—advocates “a systemic halakhic [emphasis added] solution to the plight of agunot.”

Though less charged, the same dynamic plays out in commercial law. Classical halakhah does not recognize a corporation. I am quite confident that before the era of codification, rabbis would have molded halakhah to keep pace with business practices. Today however, such attempts are few and far between. Halakhists recognize corporations via principles of secular law, but they feel powerless to develop halakhic principles organically.

The contexts of the two cases are different, yet each shows that even in the process of changing halakhah, Orthodoxy insists on its structural inability to do so.

In the past 150 years, there have been two moments when halakhah’s jurisprudential assumptions were poised to change. In each case, this was the path not taken. First, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the experience of the Enlightenment and of Jewish emancipation pushed halakhah toward insularity, leaving most Jews outside its tent. Second, in the middle of the 20th century, some dreamed that Zionism’s success would create a proactive halakhah that would grow to govern a modern, diverse, and autonomous Jewish state. But this project also failed, leaving the early state in the hands of a secular majority, halakhah in the hands of a conservative minority, and neither side talking to the other (except when trying to impose its own exclusive vision).

Today, the growth and increasing diversity of the observant population, set alongside secular Jewry’s search for a post-Zionist identity, may yet present a third moment. Will the result be different? Only time will tell.

__________________

Chaim Saiman is professor of law at Villanova Law School and Gruss professor of talmudic law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He is completing a book, Halakhah: The Rabbinic Idea of Law.

More about: Bible, Common law, Halakhah, Jewish identity, Joshua Berman, Maimonides, Mishnah, Orthodoxy, Shulhan Arukh, Talmud