The discussion of Israel’s strategic choices in Mosaic is a welcome initiative, and the essay by Ofir Haivry makes for a serious point of departure. But his essay also exhibits several weaknesses, which I shall try to outline in what follows.

In his categorization of historical periods in Israel’s unfolding regional strategy, Haivry lauds in particular the “activism” of the years under the influence and premiership of David Ben-Gurion. This, in his view, was replaced after 1967 by a more passive “search for stability,” characterized by efforts to reach accommodations with the region’s Sunni regimes. For the period now upon us, he advocates a return to the older “strategic activism,” pointing out the political opportunities (as well as some of the risks) held out by such a course.

Haivry’s historical scheme is debatable. Setting aside shifting circumstances and the idiosyncrasies of particular leaders, there has actually been greater continuity in Israel’s foreign and national-security policy than he suggests. No less than Yitzhak Shamir and Yitzhak Rabin in the 1980s and 90s, David Ben-Gurion did his own share of playing for time, waiting for the Arabs to change their rejectionist stance while doing what he could to build Israel into a strong geo-political actor. For Ben-Gurion as for his successors, Israel’s use of force was limited to impressing upon the Arabs that they could not win militarily, and to creating sufficient deterrence to prolong the intervals between necessary wars.

By the same token, Ben-Gurion’s activist “periphery” doctrine blossomed again in the post-cold-war 1990s when relations between Israel and Turkey became incredibly close. During those same years, Israeli leaders whom Haivry characterizes as passive also seized opportunities in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and India. Nor, in the first decade of this century, did Israel miss the chance to improve relations with Cyprus, Greece, the newly born South Sudan, and several African states.

What Ben-Gurion and other Israeli leaders were acutely aware of, but Haivry sometimes seems to forget, is that Israel is a small state with limited capabilities to affect its surroundings. Therefore, any activist policy is inherently limited in what it can achieve. By themselves, Israeli initiatives cannot transcend entrenched ethnic, religious, and historical forces. Israel could not “fix” Lebanon in 1982, and it has been helpless in addressing the political problems of the emerging Palestinian political entity. Most important, it is restricted in its potential influence over the strategic calculus of the major extra-regional states. Rather than enter into direct conflict with such strong powers, Jerusalem prefers to wait for better days.

Operating within the constraints of classical realpolitik, and emphasizing the pursuit of its national interests, Israel must also leave to one side the domestic politics, however distasteful—or worse—of its adversaries and/or its occasional partners. The cardinal virtue in such an approach, and one that for the most part has guided past and current Israeli governments, is the need for prudence.

Israel was happy to adopt a pro-American orientation when the Americans were ready for it in the late 1960s. A decade later, Menachem Begin responded positively to the peace overture of Egypt’s president Anwar Sadat. In the early 1990s, Yitzhak Rabin accepted the Oslo agreement after becoming convinced that the PLO was ready for a deal within the framework of his cautious, step-by step approach. Precisely because of the inability to alter significantly the strategic landscape of its mainly hostile region, Israel’s national strategy since the beginning has been focused on biding time and exploiting periods of respite in order to develop and strengthen the country’s capabilities.

If Haivry’s review of Israel’s past strategic choices is problematic, his prognosis for the future is even more so. While he acknowledges the key importance for Israel of the U.S. role in the Middle East, his discussion of this role and its potential diminishment is almost off-hand. It is certainly plausible to envisage, as he does, a lower American profile in the region, especially as the U.S. reduces its dependence on Middle East oil. But it is not self-evident that this would necessarily be bad for Israel. Despite a possible reduction in material support, less American attention to the Middle East in general would not be bad for Israel’s interests and might enhance Israel’s freedom of action.

Haivry suggests that the potential loss of the American commitment could be offset by Israeli partnerships with other powers. Conceding the unsuitability of such obvious candidates as Russia or China, he points especially to India, a rising power with which Israel has excellent relations. But the suggestion betrays a fundamental ignorance of the complexity of Indian interests in the Middle East as well as the timidity of India’s strategic culture. The plain fact is that in the near future, when it comes to global powers, Israel has no real strategic choices. The sooner Israelis understand that, the fewer mistakes will be made.

In depicting the changes that have occurred in the Middle East following the so-called “Arab Spring,” Haivry rightly notes the re-emergence of old tribal, ethnic, and religious identities at the expense of state structures. Yet his judgment that Arab Sunni dominance is at end is ill-advised. Sunni Egypt, despite its current problems, still maintains a powerful statist order, is still the most populous and strongest Arab state, and may yet bounce back as a serious regional actor. Moreover, Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel dramatically affects the latter’s strategic situation. Jerusalem cannot afford to ignore Cairo’s preferences.

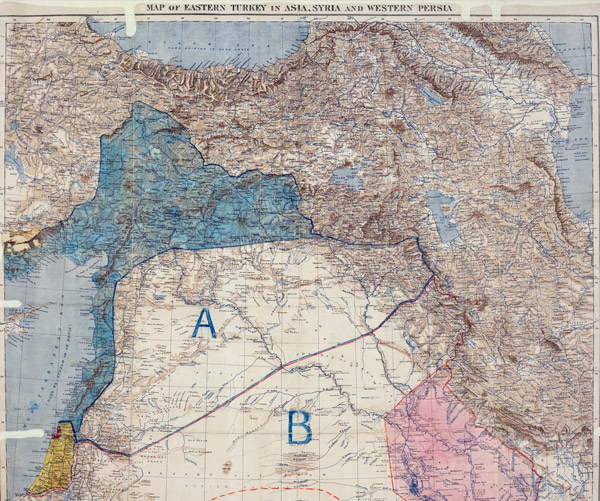

Haivry’s new “activist” strategy advises the courting of minorities in the Middle East like the Kurds, the Christians, the Azeris, and the Alawites. This makes some sense. But we should not forget that minorities are weak, and that aligning with them may estrange the more powerful majorities among whom they live. A pro-Kurdish policy like the one proposed by Haivry would exact a high price in relations with Turkey, which is still an ally of choice. As for the Lebanese Christians, they proved unreliable in the 1980s, as Haivry himself reminds us. Encouragement of Azeri separatism in Iran has also been tried and failed. That leaves the Alawites, who with good reason seem to prefer the company of Shiite Iran and Hizballah over that of the Jews.

In surveying the field of prospective Israeli activity, Haivry urges policy makers to abandon their preoccupation with the Palestinian and Iranian issues “at the expense of virtually all others.” He also stipulates, however, that the Iranian nuclear threat is in “urgent and unceasing need of the most vigilant attention.” That is understating the case. A nuclear Iran would be a game changer in the Middle East, and elsewhere. There is no need here to catalog the terrible consequences that would flow from Iranian possession of the bomb, from nuclear proliferation throughout the region, to the encouragement provided to Islamist radicals, to Iranian control of energy prices, to spin-off effects on the Indian sub-continent and in Eastern Europe.

While there is room to debate the proper Israeli response to the Iran’s nuclear program, whichever choice it settles on—a preemptive strike, or a posture of deterrence—will have tremendous implications for its status in the region, its evolving security needs, its domestic morale, and many other factors impinging on its well-being. Behaving like an ostrich toward Iran has become the favored stance of a major part of the Western community. Unfortunately, it seems to have caught up with Haivry as well.

For over six decades, Israel has steered its ship of state in the stormy waters of the Middle East with prudence and notable success. For the most part, it has done so in full recognition of the constraints upon it as a small power. In this new era of turbulence and uncertainty, the main challenge is to limit costly errors. Israel does need activism, in small doses, primarily for the purpose of incapacitating those intent on harming the Jewish state; but more important is patience.

_____________________________

Efraim Inbar is director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies and professor of political studies at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, and a fellow of the Middle East Forum.

More about: bomb, David Ben-Gurion, Foreign Policy, Iran, Israel, Ofir Haivry