I am grateful to Michael Doran, Efraim Inbar, Martin Kramer, and Robert Satloff for their extensive comments on my essay. Although we disagree, sometimes fundamentally, about many aspects of the issues raised, I regard this exchange as the start of a long-overdue discussion about the new strategic challenges and opportunities facing Israel.

To that discussion, each of the respondents contributes his own particular insights and distinctive brand of expertise. But, beyond their differences, all four approach the Middle East region from a broadly common, “realist” perspective that contrasts sharply with my own “activist” outlook. That perspective informs their individual diagnoses and, even more so, their policy proposals for Israel.

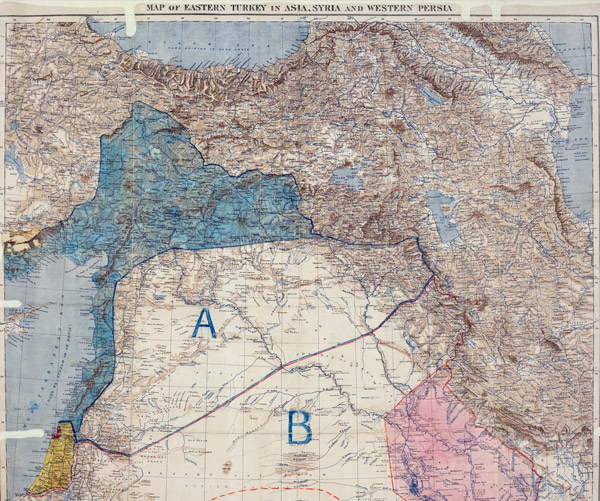

Of the four, Michael Doran is the most willing to consider active Israeli initiatives, at least as a thought experiment; but these he would direct toward solidifying the “confluence of interests between Israel and the Sunni Gulf states, Saudi Arabia first and foremost.” For his part, Efraim Inbar, the most explicit in his embrace of realpolitik, considers Israeli capabilities to be inherently limited and finds little to rely on in any of the region’s emerging minorities, whom I named as potentially new partners for the Jewish state; his watchwords are patience and prudence. Martin Kramer is more scathing: dismissing an activist stance as dangerously “romantic” and historically abortive, he agrees with Inbar about the weakness of the regional minorities, in preference to whom he, like Doran, urges cooperation with the Sunni authoritarian regimes led by Saudi Arabia, however distasteful they may be. Writing from a somewhat different angle, Robert Satloff minimizes the long-term effects of the current regional turmoil, characterizing as a “fad” the idea that the old Sykes-Picot borders are collapsing and insisting that the Middle East state system is here to stay. That being the case, he, too, would have Israel turn to the authoritarian Sunni regimes and help “shore up a system that has served Israel well and that may even, in the case of Egypt, be shoring itself up on its own.”

In brief, we are offered two or three related pieces of advice: either that Israel wait out the current regional turmoil even if doing so will take decades (what I termed the “Iron Wall” approach); or that Israel renew its efforts to establish an alliance with the oil-rich Arab states and their subcontractors Egypt and Jordan against the twin threats of Islamic jihadism and Iranian hegemonic ambitions (what I termed the “stabilist” approach); or some combination of the two. To my mind, this suggests nothing so much as business as usual.

Since, within the confines of this reply, I cannot possibly address all the points raised by my critics, I’d like instead to focus on three central dichotomies relating to action in the international arena, each of which makes an appearance in the respondents’ essays and each of which invites further clarification. They are: tactics versus strategy; “realism” versus “romanticism”; and weakness versus strength.

First: experts and politicians too often confuse tactical maneuvers with a long-term national strategy, whose goals may or may not be served by those maneuvers. For example: an ad-hoc understanding with the Saudis on the next move against Iran’s nuclear program might certainly be worth considering from Israel’s point of view; the same holds for cooperating with the current Egyptian effort to crush jihadist terrorists in the Sinai peninsula. But these are merely short-term exercises, with little long-term significance.

By contrast, any truly strategic thinking about cooperation with the Saudis and Egyptians has to take into deep consideration not only the odious aspects of those regimes but also their core ideas and interests, which are very much antithetical to those of Israel. At the moment, they share with Israel a common enemy in a nuclear Iran, but their long-term interests, no less than those of Iran itself, reside in the survival of their ruling clique and of their particular version of Islamist ideology.

The Saudis and most Gulf sheikdoms are the main patrons and funders of Salafist Islamism from Chechnya to Syria, and it is they who are propping up the new Egyptian regime of General Sisi. Their rulers, many of whom have come to power after backstabbing a father or brother, are the region’s true “realists,” masters of treachery who, when push comes to shove, will swiftly align themselves with whoever looks stronger. The moment an opportunity arises for a separate understanding with Iran, or for advancing their favored Islamist militias, they would not devote so much as a moment’s remorse to their abandoned Zionist “ally.”

So perhaps Israel should turn (back) to Turkey, a move proposed by some Israeli observers? True, Turkey’s current prime minister is fond of indulging in rank anti-Semitism, and Ankara’s patronage of the Muslim Brotherhood is disquieting, but then there’s the heartening example of a January 14 raid by Turkish police forces that netted two dozen operatives linked to al-Qaeda, some of whom were recruiting volunteers to fight with jihadists inside Syria. Well, maybe not so heartening: by the afternoon of the same day, the Erdogan government had quashed the operation and placed the police commanders on mandatory leave. Whatever this tells us about temporary internal struggles within the Turkish regime, it more certainly highlights that regime’s permanently benevolent disposition toward Islamist militancy and Brotherhood-friendly organizations like the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (of Gaza flotilla fame).

In terms of Israel’s long-term national strategy, then, those advocating an alliance with either the authoritarian regimes led by Saudi Arabia or the populist regimes led by Turkey must confront the essential nature and aims of those regimes. Even assuming their longevity (about which more below), on what grounds can anyone be confident that, even in the medium term, they would not come to pose a threat to Israel equivalent to that posed by Iran and its radical Shiite allies today? At the moment, to judge by the near-unanimity of my critics on this point, the Saudi-led option seems the more favored; how long would it take before Israel found itself required to support, or condone, the imposition by blood and fire of a Saudi-financed and Salafist-inspired government in, say, Syria or Libya?

At present, the only alternative strategy on offer to an alignment with Saudi Arabia and/or Turkey is the one I called “Iron Wall,” better known these days as “Castle Israel.” The main idea here is that, aside from the occasional “surgical” strike against missile throwers, there really is nothing strategic that Israel can or should do outside of its borders but wait and pray. Without denying the power of prayer, the Jewish and Zionist tradition would seem to encourage at least the contemplation of some action. Since, in any case, total inaction is impossible—stuff always happens—the “Castle” strategy, when it does not entirely forgo the pursuit of any goal short of survival, reduces to a policy that is only and always reactive.

Of course, it may be countered that, as my respondents insist, Israel’s options are severely constrained not only by inbuilt limitations on its freedom to act independently but also by the weakness of regional actors other than Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Yet even if history did not suggest that such assessments have too often served as an excuse for passivity, they resolutely ignore what still seems to me an inescapable strategic fact: the old regional order is crumbling, and attempts to deny this, or to patch it up, leave Israel in the position of the passengers on the Titanic who, instead of preparing themselves for survival in the ice-cold sea, furiously scrambled upward to the areas onboard that were still farthest from the water. They were really climbing hard, but the ship was sinking faster.

This takes us to the second dichotomy: the contrast between realism and a more imaginative, activist, and “romantic” approach to foreign policy. Realists, in the stock definition, deal in hard facts, in calculations, centrifuges, and cannons; romantics deal in such indefinable and evanescent materials as ideas, intuitions, and inclinations.

The contrast exists, to be sure, but in the world of experience it is seldom so clear-cut; ideas and cannons intermix on every front. Nor, when it comes to the international arena, is the realist approach always the more definitively productive—or the more realistic.

The epitome of late-20th-century realpolitik was Nixon and Kissinger’s masterful upending of the Soviets with the American opening to Communist China. But it was the “romantic” Reagan who, defying the principles of realpolitik, won the cold war by choosing not détente with Soviet Communism but competition, and who actively fought the “evil empire” by supporting unrealistic allies like Polish shipyard workers and launching the much-derided Strategic Defense Initiative (a/k/a “Star Wars”).

In the Middle East, I can think of at least one eminently “romantic” enterprise that has also been startlingly successful to date—a project called Israel, which, for more than a century, has been carried forward by a bunch of romantic Jews helped by their friends abroad. But there have also been other “romantic” projects in the region, some of them pursued or supported by Israel. The idea of a Christian-dominated Lebanon failed, but the idea of a Christian South Sudan separated from the Arab north has come to fruition. The idea of a free self-governing Kurdistan, friendly toward Israel, has failed repeatedly, yet today the reality exists before our eyes in northern Iraq; it may be snuffed out again, but it has proved it is not intrinsically unrealistic.

The effects of an activist or, as some would have it, romantic strategy are to be sought not only in direct results but also in more roundabout ways. As Michael Doran suggests, such an approach appeals to potential allies, making them more likely to value cooperation with you. David Ben-Gurion’s activism in the 1950’s registered its share of failures, but it succeeded spectacularly in attracting France and Iran into allying themselves with Israel, as well as in convincing Washington after 1956 to forgo its obsession with Israel’s relinquishing the Negev as the price for peace with the Arabs.

Indeed, if the regional events of the last three years show anything, it is the spectacle of long-established and apparently secure dictatorial regimes being either seriously rocked or altogether swept away by masses of people pursuing romantic ideas. Those ideas include, on the one hand, the bright promise of democracy and an open society and, on the other hand, the dark menace of an Islamist utopia. Think what you will about the disparate ideals moving these masses, or about the results so far of what they have done; they have surely demonstrated how risky it is to calculate the strength or weakness of a regime or a nation by the number of its tanks or the hard-currency worth of its oil reserves.

And this brings us to the third dichotomy. My respondents stress that the non-Islamist entities I named as prospective allies of Israel—emerging groups like the Kurds, Druze, Berbers, and Alawites, or states like Greece and Ethiopia—are themselves inherently weak, and that in the struggle against its major foe, Iran, the Jewish state should align itself instead with strong players like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.

I am reminded in this connection of the words on my car’s rear-view mirror: “objects in mirror appear larger than they are.” Egypt, Saudi Arabia , Turkey, Iran: not so long ago, there were two more supposedly strong players in the region, namely, Syria and Iraq. No longer. Also gone is Libya’s trouble-making regime, which for four decades hosted and bankrolled anti-Western terrorism. Even the remaining four are far weaker than they appear. Could there be something suspiciously “romantic,” one wonders, in the attachment of self-styled realists to Egypt and the oil states as Israel’s strategic anchor?

Egypt is virtually bankrupt, unable to deter “weak” Ethiopia from erecting a gigantic dam that will affect the water supply of the Nile or a small group of jihadists from calling the shots in the Sinai; it is now on the brink of reviving the same corrupt and sclerotic regime of soldiers and bureaucrats that crumbled only three years ago, a zombie government surviving on the life support of the Gulf sheikdoms that use it as a convenient sub-contractor.

As for the Saudis and the smaller Gulf states, they may still be awash with funds, which permit them to build lavish skyscrapers and to buy Yale and Harvard franchises, but money can’t buy you everything. A society too terrorized to let women drive, too afraid even to count the number of Shiites in its midst, is not a strong society, even by the starkest of realpolitik calculations.

Turkey and Iran are also, as I suggested in my essay, weaker than they appear, riven by internal challenges and, in the Iranian case, persistent popular opposition that the regime is repeatedly compelled to suppress with violence. On the other side, some of the “weak” regional players may not be so weak after all. The Kurds in particular have shown themselves to be resilient and tenacious against terrible odds, having withstood a century of relentless oppression and persecution, complete with the occasional massacre, and yet still standing and even thriving. A nation 30 million strong, on the rise in several countries, for the most part pro-American and pro-Israeli—I would take the grasshopper Kurds any day over the rotten giants of Saudi Arabia or Egypt.

States do not disappear so fast, as Robert Satloff wisely observes. But they do sometimes break up, or linger only in name, or end up following different paths. One might see a rough parallel to today’s Middle East in what happened in the Soviet bloc after the fall of Communism and empire. National states like Poland or Hungary survived and went on to prosper. The non-national states took diverse routes: the multi-national Soviet Union and Yugoslavia crumbled, the Czechs parted from the Slovaks, the East Germans reunited with the West.

Of them all, the example of Yugoslavia may be the most pertinent. First it divided into five sovereign states. Later, Montenegro and Kosovo seceded from Serbia (with the sovereignty of the Kosovars remaining contested to this day), while Bosnia, after a bloody civil war, is nominally still a single state but for all practical purposes is divided into three ethnic entities.

The same Balkanization is to be expected in the Middle East. With the artificial pan-Arabist ideology now gone, older identities are resurgent. They may be yet trampled on for decades to come, undergoing turmoil involving hundreds of thousands of casualties and savage political repression, but resurge they will.

Some of this is already happening. From the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, the three former Arab states of Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq now present a spectacle of partition into no fewer than ten (and probably more) sub-national entities, which in many cases cooperate across former borders. Not all of these will necessarily become formally independent, but as the former Yugoslavia shows, many other working political models are possible.

An additional three Arab states, Libya, Sudan, and Yemen, forming a rough line from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, are all experiencing low-intensity civil war, sometimes erupting into high-intensity clashes, permanently teetering between the status of failed states and full partition. This leaves us with Egypt and with what we might term the Maghreb Three (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia) and the Arabian Seven (Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the five smaller Gulf sheikdoms). These, too, as I have already noted, are much more unstable than appears, and it is safe to say that, sooner rather than later, some will witness serious internal strife or worse.

Should Israel seek out such allies, buy their fool’s gold, lie in their company, associate itself with their endless cruelty and turpitude? And how is Israel to convince its own people that these are allies whose cause is theirs, and with whom it is morally proper to join arms?

A long-term national strategy has to look forward, identifying weaknesses and strengths, devising options and tactics. With respect to Israel, many have historically been convinced that so small a minnow would never stand a chance against the big beasts. But Israel’s greatest assets have always been its people, their idea of themselves and of their freedom, and their resolve: resources plentiful enough to withstand and even prevail against 100-to-1 odds.

Other peoples in the region are today attempting to chart an independent course of their own, equipped with little more than similar resources. Not all of them have what it takes, but it is challenging and worthwhile to consider assisting them. In the long run, there is a better than even chance that worthy nations will come to claim their place under the sun, replacing the authoritarian Sunni Arab regimes of whose ruins it will one day be said, as Shelley wrote two centuries ago in “Ozymandias” (1818),

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

______________________

Ofir Haivry is vice-president of the Herzl Institute, a research and training center in Jerusalem. He has served on several advisory committees to the Israeli government and is a member of Israel’s Council for Higher Education.

More about: Egypt, Foreign Policy, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jewish State, Libya, Ofir Haivry, Ronald Reagan, Syria, Zionism