In more than a decade of writing about museums, first for the New York Times and now for the Wall Street Journal, I’ve reviewed history museums, science museums, political museums, and museums created by eccentric collectors. I’ve visited two museums devoted to neon signs and one to ventriloquists’ dummies, a creation-science museum and a science-fiction museum. I’ve seen human mutations preserved in glass jars and coffee beans sent to Confederate soldiers during the Civil War, a mummified cat and a fragment of Jeremy Bentham’s skin. But I haven’t seen anything quite so strange as the ways in which various Jewish communities in the United States, in Europe, and in Israel have come to depict themselves in museums.

From the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles and the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia to the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco and the Spertus Museum in Chicago, from the Jewish museums in London, Vienna, Berlin, Istanbul, and Israel to Holocaust museums in more cities than that, there are peculiarities in interpretation and advocacy that demand close examination. The objects on display at such institutions may range from a baseball signed by Sandy Koufax to the important Old Yiddish journal kept by a woman in 17th-century Germany, an excavated London mikveh from the 13th century (just before Jews were expelled from England), and fragments of parchment buried two millennia ago in Dead Sea caves. But all of these disparate instances disclose a surprisingly consistent self-image—one revealingly distinct from anything else in contemporary museum culture.

Before going farther, it is worth thinking briefly about origins. The great museums of the 18th and 19th centuries—the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (1891), the British Museum in London (1753), the Louvre in Paris (1792), the State Hermitage in St. Petersburg (1764), and many others—were encyclopedic in scope and ambition. Born, in part, of an imperial impulse, they aimed to demonstrate the geographical and intellectual range of great national powers by becoming repositories of some of the most precious objects on earth. Simultaneously, they were shaped by the Enlightenment conviction that both the natural and human worlds could be understood and even mastered by subjecting their diverse offerings to scientific analysis and discerning the universal laws at work in the midst of miscellany. The Enlightenment museum tried to answer great human questions: where did we come from? what is the significance of what we see? how have we come to be its overseer?

Why should not a Jewish museum, too, focusing on a civilization, religion, and culture older than most others engaged in such ardent display, have proceeded similarly? The last third of the 19th century might have been an especially opportune moment for such a project. Despite the continuing presence of anti-Semitism—climaxing in Russian pogroms in the 1880s and the Dreyfus Affair in France in the 1890s—many Jews had established themselves in the European middle classes, and individual Jews had achieved prominence in the political, economic, and cultural life of their respective nations.

But it didn’t happen. The history of modern Jews, after all, was not quite the same as the histories of their host peoples, and neither was the Jewish conception of history itself. For European Jews, moreover, the Enlightenment meant something very different from what it meant for others: less a matter of discovering universal laws than of disclosing the ways in which Jews might one day be considered part of universal humanity, accepted in society with the same rights as other citizens. Often, in adapting to this highly contingent face of universalism, Judaism was susceptible not so much of finding as of losing itself.

At the time, Jewish culture was also in no position to affirm its power through a collection of monumental artifacts. Outside the synagogue and the home, such artifacts enjoyed little visibility. In 1876, the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia paid tribute to a variety of American communities of faith, but no Judaica collections existed in any American museum from which to cull examples. One Jewish contribution, commissioned by B’nai B’rith, was a monument bearing the name “Religious Liberty”; it contained no Jewish imagery at all.

So far, this brief survey may suggest an unbridgeable gulf between a Jewish museum and its non-Jewish counterparts, a gulf attributable both to the nature of Judaism and, in Europe, to the still-unsettled place held by Jews in society. But by the turn of the 20th century things appeared to be changing. Everywhere, interest in ethnicity and folk heritage was growing. In 1908, the composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály traveled the Hungarian countryside, memorializing the music of Magyars; the American ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore was recording, for the Smithsonian, 3,000 wax cylinders of songs by Indian tribes; in Eastern Europe, Shlomo Zanvl Rappoport (pen name S. An-sky) was conducting an ethnographic survey among the rural Jewish communities of Russia and Poland.

Along with the amassing of music and oral testimony came the amassing of objects. At the Smithsonian, a Judaica collection was begun in 1887 by Cyrus Adler, who, having obtained the nation’s first doctorate in Semitics at Johns Hopkins University, would found the American Jewish Historical society in 1892. In 1904, the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York received a gift of 26 artifacts that it displayed in its library; they became the seeds of the Jewish Museum, which after World War II would move into its current home in the Warburg mansion on Fifth Avenue. A similarly small-scale collection, mainly of family heirlooms, was housed in the Hebrew Union College, the seminary of Reform Judaism, in Cincinnati. In 1913, the holdings became incorporated as the first Jewish museum in the United States; today its successor is the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles.

Such were the halting beginnings of the Jewish museum in the United States, and once again a difference is to be observed. In other museums, collections of artifacts were often associated with a culture’s thriving continuity; the objects were there to testify to that culture’s power and range. By contrast, a Jewish religious object put on exhibit was no longer playing its vital role in synagogue or home; taken out of its context and function, it had been turned into a relic, more closely resembling the artifacts of a fading Native American tribe in a museum of natural history than a 17th-century Dutch portrait at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Even today, a museum of Jewish religious artifacts is partly a Jewish morgue, less a tribute to Judaism’s continuity than a memorial to a world of belief left behind—in some cases, forcibly so. One of the most moving exhibits of religious artifacts I’ve seen filled an entire gallery at the Jewish Museum in Vienna. Tall glass storage cases were packed with candlesticks, menorahs, Torah finials, spice boxes, and the like, arranged not by period or style or origin but by type: objects whose provenance and function were lost when the Nazis seized them from villages and towns and cities across the Reich. Now they were monuments to a world of belief and practice wrenched not only from its habitat but from the earth.

I. The Development of the “Identity Museum”

There have long been reasons, then, for thinking of the Jewish museum as a kind of anomaly. But evidently no longer: over the last four decades, the entire concept of a museum—any museum—has been radically transformed, with repercussions felt in Jewish museums as they are everywhere else.

To grasp the change, we can set up two poles. Traditional museums strove to fulfill the elevated Enlightenment ideal of uniting differences (“out of many, one,” as the great seal of the United States had it); new museums, founded on the conviction that too much was slighted or deleted in the past, prefer to highlight difference and to emphasize distinction. Traditional museums were culturally Eurocentric in spirit; new museums are multicultural. Traditional museums often focused on heroic figures and world-shaking events; new museums are preoccupied with the democratic and the demotic. Traditional museums cherished the authoritative; new museums are “conversational.” Traditional museums had their foundation in their collections; new museums have their foundation in their audiences. Traditional museums celebrated the universal; new museums celebrate the particular.

Rebelling against and rebuking their predecessors, the latest museums have created a new genre, one that may epitomize our era as neatly as the imperial and Enlightenment museums did theirs. That new genre is the “identity museum,” whose origins lie in a mode of politics that developed during the 1960s.

In the United States, such museums typically bear a hyphenated name. Thus, in the last few decades, there have been new Chinese-American museums, new Japanese-American museums, an Asian-American museum, African-American museums, an Arab-American museum, a Hispanic-American museum, American Indian museums, and even a Nordic-American museum. On the national mall in Washington, DC, the most important African-American museum in the country is expected to open in 2016. And now there is heavy lobbying for another national museum on the mall devoted to Hispanic Americans and yet another telling the history of American women.

The identity-museum genre is now so prevalent, and the rules of its displays so formulaic, that they are almost never commented upon or even recognized. But the genre is one that, with a few modifications, seems all but ready-made for Jewish museums. After all, every Jewish museum is, by definition, an identity museum. Within this framework, one might think, such a museum would come into its own, aiming not for encyclopedic reach or Enlightenment insight but telling a particular story and telling it well, with or without collections of objects. (In fact, some identity museums show scarcely any objects at all.)

But, as a few representative cases will show, something else takes place when the identity in question is Jewish.

Consider, to begin with, a museum that seems to have been consciously designed as a model identity museum: the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, which opened in 2010. Overlooking Independence National Park, the Liberty Bell, and the National Constitution Center, it tells the history of the Jews in the United States as if from a similar perspective, keeping certain ideas and ideals in view. Its theme, in 25,000 square feet and three floors of exhibition galleries, is American freedom and what Jews have made of it. In chronological order, the museum’s narrative is divided into “Foundations of Freedom 1654-1880,” “Dreams of Freedom 1880-1945,” and “Choices and Challenges of Freedom 1945-Today,” punctuated by multiple examples of migration, assimilation, discrimination, discrimination overcome, and re-invention.

There is much to see here. The 18th-century material, which may be the least familiar, includes such rarities as an intriguing 1722 brochure by Rabbi Judah Monis explaining why “the Jewish Nation are not as yet converted to Christianity.” (Monis may well have had a personal stake in this explanatory exercise, having himself become a Christian so as to be allowed to teach Hebrew at Harvard College.) Then there are images of 19th-century Jewish settlers in the American West, and costumes from 19th-century Jewish charity balls; 20th-century accounts of Jews in crime and in the world of entertainment, and anecdotes about Jews as distillers and as philanthropists. Near the narrative’s end are film clips from the 1960s counterculture and feminist movement, leading into a gallery in which late-20th-century American popular culture unfolds, its Jewish elements italicized.

This is a vision of modern Jewish history as a kind of apotheosis of popular U.S. history, a tribute to the adaptive possibilities of American-style freedom. And here, for better and for worse, we can already see major differences between this and the typical identity museum.

Typically, the contemporary American identity museum tells of a group’s distinctiveness and unity by recounting its multiple attempts to join the nation’s mainstream society. Grievous sufferings are undergone, primarily because of racism and intolerance. But then, after refusing to surrender or assimilate, by fully embracing its own identity and aggressively affirming its rights, the group begins to undermine the rigid prejudices of the surrounding culture and to attain freedom on its own terms—terms that by its lights are truer to American ideals than is America itself. In keeping with the hortatory message, the museum also typically serves as a community center and meeting place whose purpose is to promote and solidify the identity it celebrates.

Almost no identity museums veer from this narrative; it is applied to Japanese Americans, Arab Americans, and Hispanic Americans. Even Native Americans and black Americans, whose histories are distinct and of a wholly different kind, maintain the general pattern. The one overwhelming exception is the Jewish American museum, and the differences are profound and illuminating.

The simplest difference can be seen in the Philadelphia museum. In other identity museums, the surrounding society is portrayed as forbidding, and any success obtained has less to do with opportunities offered than with opportunities seized in the face of hard resistance. The Philadelphia museum, like many other Jewish American exhibitions, suggests the opposite. Jews do not succeed despite America; they succeed because of America—an assertion that would be near-heresy at the typical identity museum.

This may have something to do with the fact that Jewish immigrants themselves often celebrated and gave thanks to America virtually from the moment of their arrival, so dramatic was the difference from the worlds they had left behind. A notable artifact at the Philadelphia museum, composed for Congregation Beth Shalome of Richmond, Virginia, is a Hebrew prayer for the new American state in honor of the first Thanksgiving declared by George Washington in 1789; it is in the form of an acrostic, with the first letters of each line spelling out the president’s name. As in other identity museums, we learn here that Jews, too, had to struggle against flaws in the American dispensation, but that didn’t happen because they proved truer to American ideals than America itself. Nor did their success come about, as is contended in nearly every other identity museum and exhibition I have seen, through the triumph of identity politics and the liberationist counterculture. America deserves, and receives, credit.

The American theme in Jewish museums goes even farther. Consider the Skirball Center in Los Angeles. A major force in the city’s cultural life, the Skirball contains a performing-arts space, conference halls, libraries, event spaces, and gardens. Beginning with the small collection of Judaica in the pioneering Jewish museum at Hebrew Union College, the Skirball now holds more than 30,000 Jewish artifacts, many of which make an appearance in its permanent historical exhibition. But they are not the main point of that exhibition, which instead focuses on the multiple journeys taken by Jews over the millennia, concluding not with the Jewish people’s return to Zion but with the creation of a new Jewish life “At Home in America.” So impassioned is this attachment that the museum includes an enormous reproduction in two-thirds scale of the Statue of Liberty’s torch, and among its other artifacts is a 20th-century Ḥanukkah lamp in which each candle is held up by a Statue of Liberty.

As in the Skirball, so, too, at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum. An exhibition there in 2012 featured a reproduction of a stained-glass window from Sherith Israel, one of the city’s first Jewish congregations, that shows Moses with the Ten Commandments. The window can still be seen in the synagogue. There as in the reproduction, Moses stands not before Sinai but in front of the magnificent Half Dome crest in Yosemite National Park: the source, evidently, of divine authority in the new Promised Land, and a sign that at least in some respects, today’s Jewish identity museums are treading a well-worn path.

But this is extravagantly unlike any other kind of American identity museum. Within such a museum of hyphenated identity, the accent falls on the term before the hyphen, emphasizing the Chinese, the Indian, the Arab, the black, de-emphasizing if not devaluing the American. In Jewish museums, the emphasis shifts in the other direction. Despite the presence of discrimination and hardship, America, and the American promise, are the decisive factors.

So far, so good. But that’s not the only contrast between the two types. Unfortunately, as faithful and historically accurate as Jewish museums might be to the promise of American democracy, they simultaneously tend to turn a peculiarly blind eye to the promise, and the substance, of Jewish identity itself. That is the second and deeply problematic contrast—one that would seem to call into question the very purpose of the identity museum itself.

In the case of most minorities, to judge by the story told in identity museums, the freedom gained in the United States has been the freedom to become most like themselves. For their part, many Jewish American museums are more preoccupied with the freedom of Jews to become American than with the freedom of Jews to remain fully Jewish. In fact, there is often a suggestion that exercising the former freedom is precisely how Jewish Americans are most true to their identity.

Thus, pride in Jewish American identity is measured in terms of how much that identity has contributed to the American scene. “However Jewish identity is defined,” we read at the Skirball, it has led to immense achievements and “its vitality is reflected in literature, film, music, drama, education, science, commerce, and technology.” Similarly, in the roster of Jewish achievements at the Philadelphia museum, in which Bob Dylan and Albert Einstein and Bella Abzug merit distinctive mention, I can’t recall any significant discussion of how Jewish identity has expressed itself in Jewish terms—in advancing Jewish scholarship, say, or in interpreting Jewish religious texts, or in formulating deeper understandings of Jewish peoplehood, or in articulating collective Jewish interests. When divisions within and among Jews are recognized, there is little doubt which parties are considered more authentic: namely, those whose ideas are most congenial to the vision of the museums’ founders. In these institutions, Judaism, including American Judaism, is transfigured into a kind of Jewish-inflected, progressive-style-Americanism.

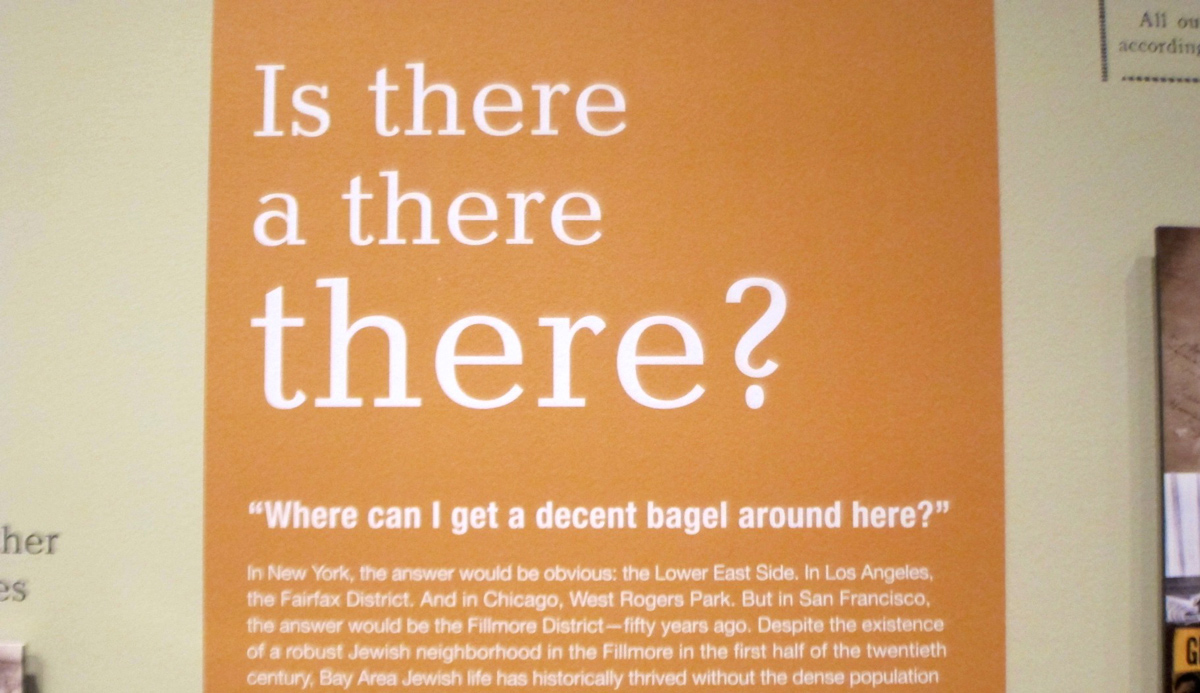

Left unexamined in this transformation is how unique, historically, the American emphasis on individualism was, and how dramatically it altered the organizational coherence that Judaism had typically possessed in other nations over the course of two millennia. So radical has its effect been that there are times when the specifically Jewish aspect of American Jewish identity can even be celebrated for its seeming vacuity. A featured quotation in an exhibition at the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum a few years ago was: “The Jewish Film Festival is my favorite Jewish holiday.” At the Skirball’s Noah’s Ark exhibition for children—a marvelous interior playground inspired by the biblical story—any hint of that story’s biblical character has been meticulously eliminated. Not only is there no God, but the Ark has become “a symbol of human resilience,” and the divine promise encapsulated in the biblical rainbow is now an instruction to children to “Build a Better World.” Underscoring the point, the Skirball’s literature about the Ark encourages children “to work together for the greater good, to strengthen connections within and among families, to value diversity within community, to respect and protect minorities.”

Neither the Philadelphia museum nor the Skirball nor the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum is unique. In exhibition after exhibition, at one museum after another, the impression is conveyed that over time, an antique form of particularism—the Jewish religion, and the Jewish people who have been the historic carriers of the Jewish vision—has been evolving into a new, ardently welcomed form of universalism. At the San Francisco museum, designed by the celebrity architect Daniel Libeskind, the Hebrew word pardes, orchard—a term taken by medieval Jewish exegetes as an acronym referring to four types of biblical interpretation (and associated etymologically with the English word “paradise”)—is a crucial symbol, made visible in semi-abstract Hebrew characters. But for the museum, it does not, in any exhibition I have seen, offer a lens into understanding Jewish history or belief or practice. Instead, we are instructed that pardes means “creat[ing] an environment for exploring multiple perspectives, encouraging open-mindedness,” and “acknowledging diverse backgrounds.”

The Skirball, for its part, approvingly notes that American Jews embrace the message of Passover by “taking active roles in civic life and supporting the global struggle for human rights”—that is, they fulfill their Jewish identity by becoming advocates of other groups and their identity sagas, as if the notion of “healing the world” were now the defining Jewish principle. Near the end of the Skirball exhibition, a video shows faces of varied ethnicities morphing into each other, the obvious implication being that all identity is fluid and that none, or at least the Jewish variety, is to be celebrated in itself. With Americanism fading into multiculturalism, tinged by the remnants of New Age spirituality, nothing is really essential to Jewish American identity other than simply declaring it. In no other setting of which I am aware is group identity defined by the abnegation of one’s own group identity.

II. Group Identity and the Jews

I don’t want to leave the impression that the celebration of group identity at non-Jewish identity museums is without problems. Even apart from their frequently reflexive distortions of the American character—distortions unnecessarily applied even when criticism is deserved—the genre is in fact riddled with problems. These are instructive in their own right and may help deepen our inquiry.

When, for example, the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington opened in 2004, identity politics were so powerful that early exhibitions allowed individual tribes to decide how they were to be portrayed. Indulgently overseen by curators, they would “tell their own stories.” The result was an unmitigated disaster, as artifacts once analyzed and exhibited in conformity with the highest academic standards were stripped of all scholarship, rendering history meaningless. The entire conception of the museum was based on a fantasy, implicitly asserting that tribes as different as the Tapirapé of the Brazilian jungles and the Yupik of Alaska should cohabit under the single political canopy of the “American Indian” identity, protected by a gauze of romance. Although the museum has since made progress toward repairing the damage, it still has not shed its spirit of advocacy, which is an unavoidable aspect of the identity-museum genre as a whole.

Indeed, I can’t think of a single identity museum that is not disfigured by historical over-simplification and even delusion, including the Wing Luke Asian American museum in Seattle, which lumps together groups and cultures (Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodian) that have almost nothing in common and have often been actively hostile. What supposedly gives these disparate groups a single “identity” is their shared experience of racism under the lash of White America—though history shows they were well acquainted with racism and warfare at each other’s hands.

In fact, a peculiarity of this and other ethnic museums (like the Museum of Chinese Americans in New York) is that it becomes unclear why immigrants from a group subjected to such horrific racism should have kept arriving in such great numbers—a puzzle that, so far as I know, is never explained in any identity museum. Instead, racism is invoked mainly to disguise obvious differences and define a single identity, which is then used to create a political force. Even a more innocently constructed identity triggers distortion, as at Seattle’s Nordic Heritage Museum, which strives to pull Norwegians, Finns, Danes and Swedes together in a Nordic union with a shared story—never mind that Norway long celebrated its constitutional independence from the Swedes.

It is of some relief, then, that Jewish museums have seen fit to invert or ignore much of the identity-museum mythology, including the political construction of identity. This is not because Jewish identity has been seamless and indivisible. There have been vast differences among Jewish subcultures throughout history, not to mention outright hostilities so radioactive that matches between couples from conflicting traditions or ritual approaches were considered as abhorrent as marriage with non-Jews. But there was generally also a sense of a Jewish identity transcending such differences. In addition, while Jews have been hated and faced discrimination for centuries, such discrimination or racism, unlike what is alleged in the case of many of the other hyphenated identities on display in museums today, did not form the unifying aspect of Jewish identity, any more than Jewish identity was created in order to paper over internal divisions, real or perceived. Jewish identity existed despite such external racism and internal division: a connection far stronger than any between the Yupik and the Tapirapé or the Japanese and the Koreans.

What, then, was the basis of that more profound sense of identity that energized the Jews and ensured their survival as a people? Again and again, American Jewish identity museums strip away the information and complication needed to answer that question, rendering it unclear just what Jewish identity might amount to other than the least common denominator among all those who call themselves Jews. What has Judaism been as a religion, a living congeries of beliefs, laws, and practices? Who have the Jews been as a people and what does Jewish peoplehood imply or require of them? How have those laws and the texts embodying them made their peace, or failed to make their peace, with American life? To what degree, for that matter, have certain threads of Jewish experience and Jewish thought contributed to forming the very curious and anomalous phenomenon that today’s museum curators display as Jewish identity?

By neglecting this kind of specificity—the aspects of Jewish life that are the least up-to-the-minute American—the Jewish identity museum suggests that the real achievement of America is the successful shedding of that same, superfluous specificity: a sloughing-off of the very identity the museum was built to celebrate.

III. The Problem in Europe and in Israel

The condition I’ve been describing is not entirely unique to America, though of course emphases elsewhere vary. Consider the Jüdisches Museum Berlin, which opened in 2001 and was promptly hailed as marking a milestone in German-Jewish relations. There may be worse Jewish museums in the world than this one, but it is difficult to imagine any quite so banal and uninspiring. The largest of its kind in Europe, the Berlin museum is a national institution, devoted to exploring the history of a people whose host nation was once intent on eradicating it.

The Berlin museum also fits some aspects of the identity-museum model, whether Jewish or non-Jewish. Chronicling the history of Jewish travails and struggles against German racism, discrimination, and murder, it culminates in the triumph represented by the survival and revivification of the Jews and by the existence on German ground of this very museum. Because the Berlin museum is not in fact an American Jewish museum, and because the history it tells is infused with an incomparable degree of trauma, it hesitates to accord too much credit to Germany. And yet, though its narrative begins with an evocation of mass murder that will then interrupt the arc of Jewish success, it is meant to end, if not quite in mutual redemption, at least in a kind of mutual embrace. Moreover, one senses throughout a constant urge, despite the interruption of the Holocaust, to praise Germans and Germany for all they have done and continue to do for the Jews—and, through the Jews, for the world—almost as if this were a more familiar Jewish museum hailing the virtues of America.

Perhaps worst of all in this connection is the adoption by the museum of the American preference for generalizing the Jews out of their own identity. In the museum’s catalog, W. Michael Blumenthal, until recently its director (and a former U.S. Treasury Secretary), explains that its story “far transcends” the history of German Jewry, demonstrating “a widely shared determination” to apply its lessons “to societal problems of today and tomorrow” and promoting “tolerance toward minorities in a globalized world.”

So the museum both woos the German host and hails the shedding of overly Jewish particularity—with the Holocaust looming overhead. The museological results are almost schizophrenic. The building by Daniel Libeskind, with its twists and breaks and deliberately jarring internal passages, screams pain in deliberate (and overly obvious) allusion to the Holocaust. Yet the exhibition within the walls keeps straining to affirm harmony and forgiveness. Discordant historical facts seem only to get in the way: you have to watch brief films to get any historical background about serious problems in this long-term romance. And you are still left with only the vaguest notion of what Jews believed or how and why they survived. We are informed that learning and texts were highly valued in Jewish tradition, and we see an electronic page from the Talmud and a prayer book; but we’re given no real sense of their content or how they shaped Jewish consciousness or Jewish life.

After its historical narrative reaches the Enlightenment, the museum finally seems to breathe a sigh of relief as, abandoning any effort to explain matters of substance, it turns instead to recounting the ways in which Jews became central figures in German banking, commerce, journalism, and the arts: activities that along with other examples of Jewish achievement are no doubt regarded as of greater contemporary interest. Throughout, the museum’s interest in blurring tensions between Jews and Germans makes the German past seem more enlightened and the Jewish past less particular. Becoming a celebration of ersatz tolerance and fake universalism, the museum, like too many of its American counterparts, suggests that Jewish identity is best realized through its shrinkage.

Nor, I am sorry to report, is this an issue only within the Diaspora. In slightly different form, some of the same factors bedeviling Jewish museums elsewhere come into play at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, an institution as close to being a national museum as any in the Jewish state.

As I noted early on, national museums are not meant to be modest or self-effacing. Reflecting the vision of the nation that created them, they strive forthrightly to show how that nation thinks about itself and its place in the world, what it values, how it interprets its past. The Israel Museum adds another level of intricacy to this exercise because it is, like its nation, so young, and because the story it tells, like the story of the Jewish nation, is so old. It’s thus a matter of special interest to see how the museum has chosen to present itself since a major redesign that was completed in 2010.

This is still an extraordinary museum, but the recent changes are significant. The most enduring impact of the historical collection is delivered not by the museum’s Judaica, or its manuscripts, or its art works, but by its archeological objects, whose story is coordinated with the findings of biblical scholarship and comparative religion. That story is directly related to the story both of the Jews as a people and of the other peoples who have lived in the land now called Israel. But, in subtle ways, the museum’s presentation tends to de-emphasize its Jewish—and therefore its national—element in a version of the same universalizing impulse we have been tracking elsewhere. The ambition, according to the museum’s director James Snyder, is to “open visitors up to the experience of world culture.” The museum itself, he suggests, “is really about intercultural resonance and inter-communal engagement,” and its own “experiential journey is universal in nature and embracing of all time.”

Think how strange a move this is for a museum that presumes, on the face of it, to be an advocate for the particular. The Israel Museum goes about the move, as I’ve noted, very subtly, and mainly by means of emphasis; in the core archeological exhibition, that emphasis falls specifically, and to an unsettling degree, on the word “land.” Labels tell us that nearly every object here is from a different region of the Land, and that the Land is the crossroads of cultures, “home to peoples of different cultures and faiths for more than one and a half million years.” We stand, the museum tells us, amid a confluence of influences and peoples.

True enough—and true, too, that in Jewish tradition, the centrality of the Land is indeed undeniable, with the land of Israel often referred to simply by the Hebrew word ha’aretz, the land. But what emerges in these historical displays is an apparent effort to avoid any equally emphatic attention to the presence in the Land of the People and the Religion that endowed it with its significance—to avoid, in short, any taint of particularism. As it traces the paths of all nations through the Land, the museum seems positively uncomfortable with the claims of Israel and Jews: an approach especially obtrusive in a museum not just about the land but about the nation, the people, and the national religion. It is difficult to imagine the Louvre or the British Museum assuming a comparably self-negating stance.

To be sure, the avoidance here has a history behind it. The idea of a national museum in “the Land” was first conceived by the East European sculptor Boris Schatz, who came to Palestine in 1906 and promptly created the Bezalel art school and museum in Jerusalem. When Marc Chagall visited in 1932, according to the Israel Museum’s literature, he “thought that the museum was too ‘Jewish’”: the very affliction that Jewish identity museums—and only Jewish identity museums—worry about to this day.

IV. The Problem of the Holocaust Museum

The particular is too particular. The Jew is too Jewish. The religion is too religious. The nation is too nationalistic. The Jewish-identity museum, unlike every other example I know of, undercuts the identity to which it is paying tribute, escaping to the apparent comfort of an Enlightenment vision but without the Enlightenment’s confidence in its vision. In Germany and Israel, as in the United States, the museum’s voice, at the very moment it might be raised in explication or celebration, is instead qualified, hesitant, self-effacing.

Why this unease and this wariness? Is there any realm immune from its doubts? Surely, I used to think, the Holocaust museum must be the exception, dedicated as it is to exploring the nature and the consequences of the Nazi evil that reached across all differences and variations and made Jewish identity the very center of its maleficent attention. Surely there is no equivocation about the Holocaust.

Well, surely there is. Let me offer one prime example: the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. Every visitor to this museum, before gaining access to the galleries that tell the history of the Holocaust, must choose one of two doors through which to enter. One is invitingly labeled “Unprejudiced”; the other, illuminated in red, screams “Prejudiced.” No contest, right? But the first one doesn’t open; only the second does. Evidently, the guards at Auschwitz are not alone: we are all prejudiced.

Once in the galleries, you are presented with more evidence of intolerance’s ubiquity. A streaming news ticker runs above panels exemplifying “Hate in America.” Two Latinos are beaten on Long Island. A white supremacist shoots Jews in Los Angeles. A Sikh is murdered in a post-9/11 “hate crime.” A homosexual student is brutally murdered in Wyoming. On one panel is a description of the Oklahoma City bombing; on another, the attacks of 9/11.

Walk a little farther and you come to a mock 1950s-style diner where a television monitor broadcasts a staged news video about a drunken teenage driver injuring his date on prom night. We are asked to vote for the party most responsible: the liquor-store owner who illegally sold the booze, the parents of the drunk driver, the teenager himself? “Think,” we are urged by the signs: “Assume responsibility,” “Ask questions,” “Speak up.” And still we haven’t been led into the central exhibition about the Holocaust and the murder of six million Jews—not until we have successfully negotiated this “Tolerancenter,” as it is called, which strains to tie together slavery, genocide, prejudice, discrimination, and hate crimes while educating even elementary-school pupils in “the connection between these large-scale events and the epidemic of bullying in today’s schools.”

The Museum of Tolerance is hardly alone. No Holocaust museum, it seems, can be complete without invoking other 20th-century genocides in Rwanda, Darfur, or Cambodia as proof that the supposed lessons of the Holocaust must be taught even more fervently than heretofore.

There are two problems at work in these kinds of analogies. The first is the immediate and almost reflexive urge to universalize the Holocaust, so that genocide is not “just” a matter of and for Jews. The second is the way this “universalization” takes place, reducing everything to the lowest and least significant common denominator. First come Auschwitz and Darfur, then come Auschwitz and bullying.

In tandem, the two impulses wreak havoc with both history and moral clarity. In his announcement of the plans for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, President Jimmy Carter hailed the opportunity to commemorate “eleven million innocent victims exterminated—six million of them Jews.” But as Walter Reich, the founding director of the museum, has pointed out, the figure of eleven million was pulled out of thin air. Evidently, according to the historian Yehuda Bauer, it had been invented by the Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal “in order to make non-Jews feel like they are part of us” and thus “create sympathy for the Jews.” The effect has been rather the opposite. Historians suggest that perhaps a half-million non-Jews perished in Nazi death camps, not five or six million. So the inflated number, if anything, may well have served to undermine Wiesenthal’s desire to create sympathy specifically with the Jews, while also setting a precedent for those who for any reason would wish to universalize the Holocaust into platitude.

This was evident, too, at the Anne Frank Huis in Amsterdam. When I visited more than a decade ago, the sober tour through the notorious annex where the young diarist and her family hid from the Nazis led into a video-laden gallery chronicling nearly every contemporary social injustice that could be enumerated. As the museum’s website informs us, an Anne Frank School—they are being established all over the world—“obliges itself to stand up for freedom, justice, tolerance, and human dignity and to resolutely turn against any form of aggression, discrimination, racism, political extremism, and excessive nationalism.”

As if in imitation, the Museum of Tolerance also recently mounted an exhibition about Anne Frank. A carefully constructed history gives way to a final gallery in which touchscreens display the Diary’s supposed lessons for “making the world a better place” by, among other things, “Valuing Family,” “Speaking Up,” and “Appreciating Nature,” with each theme accompanied by Anne’s commentary and an example of how the principle might be applied today. Thus, under “Assuming Responsibility,” we learn that, for Anne, people should “review their own behavior,” and that a contemporary example of the same rule might be: “I’ll not talk behind my friends’ backs.” Visitors are then asked to make pledges of their own. “I’ll start attending my child’s school-board meetings,” one read during my visit. Another: “I’ll keep my dog on the leash when we walk in the town forest.”

Thus is history distilled into tripe, horror into effervescent inanity. Out of the history of the Holocaust, the museum teases unconvincing homilies to the effect that the root cause of genocide is prejudice and intolerance—by now an international delusion. The impulse to tell the Holocaust story only in the context of such elaborate generalizations is also what has helped justify its inclusion in school curricula and win public financing for museums. The Museum of Tolerance obliges with its own series of educational programs, including “Tools for Tolerance for Professionals”: sensitivity training for educators, law-enforcement officers, and corporate leaders. The history that emerges from all this is history stripped of distinctions: that is, no history at all.

Actually, the deeper one looks at the Holocaust itself, the more unusual its historical circumstances become. Nor was the cause of the Nazi mass killings “intolerance” but something else, something still virulently prevalent in parts of the world and still scarcely understood: the murderous hatred of Jews. This is a difference not just in degree but in kind. And how central is intolerance to genocide, anyway? Many intolerant societies don’t set up bureaucratic offices to supervise efficient mass murder. Many people who consider themselves very tolerant are nonetheless blind to their own hatreds. There are even intolerant people who would find genocide unthinkable.

Of course, I am dwelling on some of the most problematic examples of Holocaust museums. I could easily point out the contrasting virtues of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, where the horrors unfold with calm and precision—until they overwhelm—or the main exhibition at the extraordinary United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. True, even Yad Vashem can’t resist a homily, in the form of the message silently delivered when, after zigzagging downward and then upward through the exhibition the visitor emerges, after all that carnage, to behold the flowering Judean Hills and the strong, confident state of Israel; but this message, a Zionist one, is itself anchored in the most fundamental Jewish sources and the strongest of the Jewish people’s millennial dreams. The Washington museum, more problematically, leads you from the history of the Holocaust, narrated and choreographed with such exquisite care as to take your breath away, into a series of changing exhibitions that mitigate the point with other examples of injustice, genocide, and, yes, intolerance.

The homiletical approach to the Holocaust has broken down almost all inhibitions about using the Holocaust as an analogy, even though the eagerness to analogize is a sure sign of misuse. To judge from recent history, moreover, the analogies with which we are bombarded, far from making genocide unthinkable, have helped make it seem commonplace. I’m not familiar with any other tales of historical trauma that feel obligated to end by saying—hey, you have to pay attention, this isn’t just about us. But that, to repeat, is one of the crucial intellectual moves of secular Jewish identity in today’s world.

V. The Exceptions

If my survey of Jewish museums and exhibitions has seemed a little intemperate, that is partly because I have largely omitted discussing permanent exhibitions that work, or temporary exhibitions that have created a lasting impact. A short list of these would include, for example, an exploration of Emma Lazarus at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City; Yeshiva University Museum’s shows about the Dreyfus Affair or Jews in the American Civil War; an exhibition about Nazi propaganda and another on Nazi eugenics at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; an older exhibition in Israel’s Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum and an unexpectedly affecting Holocaust museum in Richmond, Virginia.

Common to all of these examples are a dedication to historical detail, a reluctance to create loose analogies that don’t withstand scrutiny, and perhaps above all the sense that there is much more to Jewish identity than its secularized and politicized incarnation now prevalent in the museum world: something deserving of the deepest pride and most scrupulous study rather than the shallowest pride and least scrupulous study. It is sobering to think that this view, so dominant in the museum world, really does reflect the attitudes of a large number of contemporary Jews about themselves and their Jewishness; other evidence, notably the much-analyzed findings in the 2013 Pew survey of American Jews, seems to suggest that this is in fact the case. Shouldn’t Jewish museums—so presumably preoccupied with virtuously “repairing the world”—start to think about repairing a bit of what they take to be their own subject?

Finally, a recent special issue of the journal East European Jewish Affairs, dedicated to the revival of Jewish museums in Russia and the former eastern bloc, suggests that in those regions, at least, the unspoken rules might be quite different. Having been long deprived of the opportunity to speak about or examine the Jewish past openly, today’s Jewish museums in the former eastern bloc unabashedly memorialize and celebrate the once-vibrant identity of their communities and seem to show little interest in the self-imposed cultural shrinkage that haunts Jewish identity elsewhere. The most important example of a new Jewish museum in this region is the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, with its main exhibition overseen by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett; although I haven’t had the opportunity to visit it, I would like to think that it, too, succeeds in avoiding the pitfalls of its American and West European (and Israeli) counterparts.

Alas, for most of those counterparts I can’t hold out much hope. Nothing, it seems, will shatter their paltry view of Judaism, Jewish history, and Jewish public responsibility. Minimize your profile, mute your pride; be overly indulgent, even perversely so, of the tastes and priorities of the surrounding culture; resist any hint of “difficult” scholarship or religious thought; avoid any sort of self-assertion that might infringe the dictates of political correctness or intellectual fashion: these are the defining characteristics of the modern Jewish identity museum. As for those who insist on holding out for a more rooted and substantive view of Jewish identity, they will have to rely on the small handful of exceptions, or start to think about what it would be like to create a new Jewish museum in the first third of the 21st century.

———

Jewish Museums:

- Jüdisches Museum Berlin

- National Museum of American Jewish History, Philadelphia

- Jewish Museum London

- Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, Berkeley

- Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco

- Israel Museum. Jerusalem

- Illinois Holocaust Museum, Skokie

- Derfner Judaica Museum, Hebrew Home for the Aged, the Bronx

- Holocaust Museums in Israel

- Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust

- Museum at Eldridge Street, New York

- Kupferberg Holocaust Research Center, Queens College

- Museum of Tolerance, Los Angeles

Jewish-Themed Exhibitions:

- The Valmadonna Trust

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- The Dreyfus Trial

- Houdini

- Protocols of the Elders of Zion

- Irene Nemirovsky

- History of Jews in New York

- Jews in the New World

- The Catskills

- Abraham and Three Faiths New York Public Library

- Curious George

- William Steig

- Sarah Bernhardt

- Iraqi Jews

- Emma Lazarus

- Illuminations and Jewish Texts

- Nazi Eugenics

- Resistance to the Nazis

- Children and the Holocaust

- France under the Nazis

- Nazi Propaganda

- Anne Frank

- Collaborators, Holocaust Museum

- Crossing Borders: Books at Jewish Museum

- Abraham Lincoln and the Jews

Identity Museums:

- Identity Museums on Display

- National Museum of the American Indian

- Museum of Chinese in America

- 1,001 Muslim Inventions, New York Hall of Science

- Nordic Heritage Museum, Seattle

- Church History Museum: Mormonism, Salt Lake City

- Arab-American National Museum, Dearborn

- Museo Alamedo, San Antonio

- Problems with Indian Patrimony

- Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco

- Wing Luke Asian Museum, Seattle

- Sacred and Secular Museums, Istanbul

- American Indian Treaties, Washington, DC

- Indian Art and Nagpra

- Jefferson’s Slaves: National Museum of African-American History and Culture, Washington DC

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jewish museums, new-registrations