Turbulent times tend to produce turbulent voices—some of them insidiously persuasive. In particular, such times offer a fertile breeding ground for peddlers of conspiracy theories. Adducing supposedly definitive evidence of hidden hands, secret cabals, and sinister machinations, they feed the suspicion that unseen forces operating in the background of events are acting to undermine settled arrangements, pervert sane policy, scramble and transform political reality in order to promote their own diabolical aims—if not, indeed, to achieve total domination.

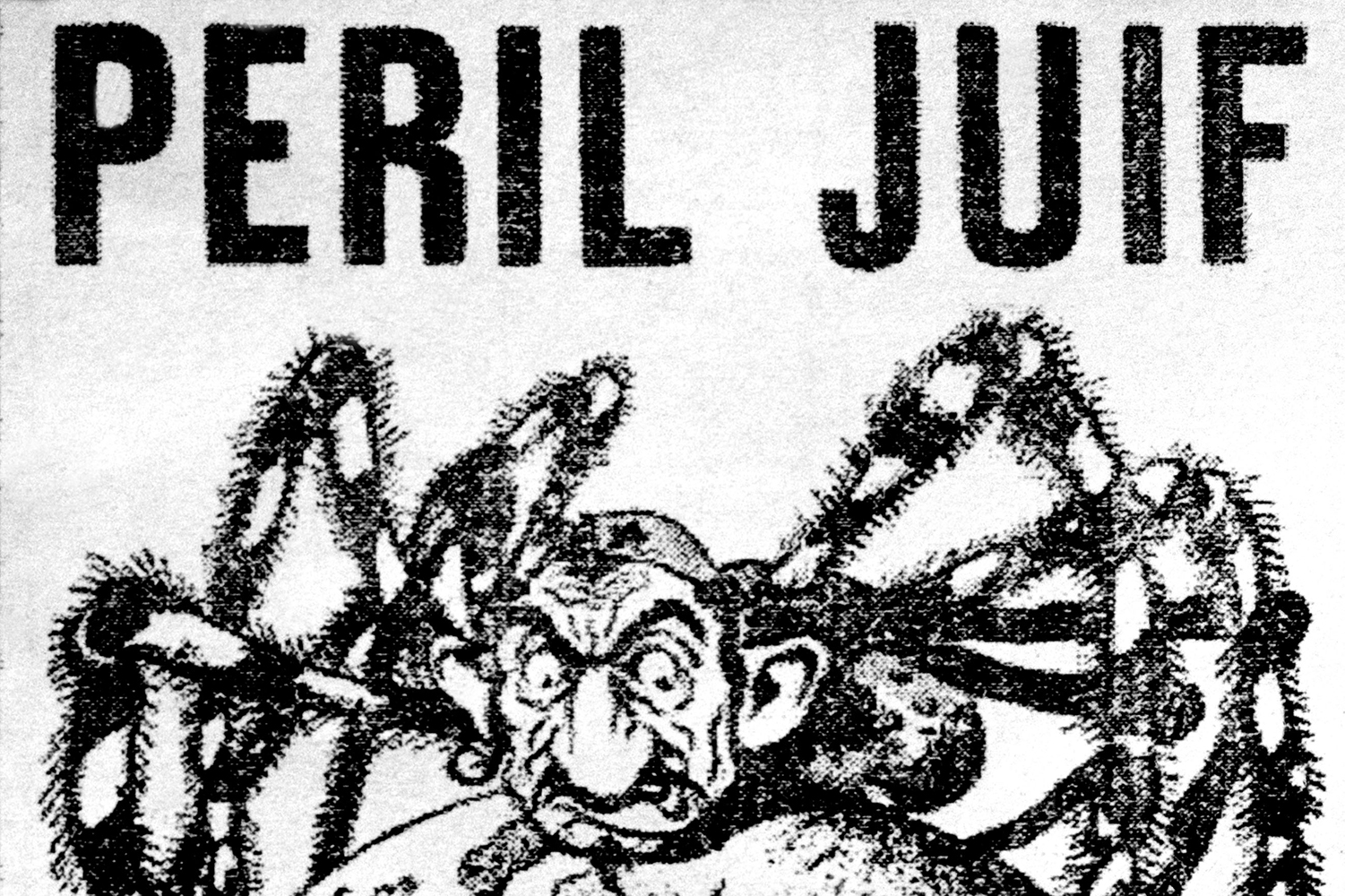

Easy to dismiss as the ravings of paranoid crackpots, such theories have, in some places at some times, infected the minds of both elites and multitudes of ordinary people at every level of society. Perhaps the most notorious textbook case is The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a pamphlet that, appearing early in the 20th century and summoning “proof” of a monstrous Jewish conspiracy to enslave all of humanity, would become one of the most famous and important political documents in world history.

Exposed repeatedly as itself a monstrosity—an outright forgery and fraud—the Protocols would nevertheless enjoy the proverbial nine lives before it faded from view in the aftermath of World War II. Or did it? In some less enlightened parts of the globe, it continues to live on, circulated often by cynical governments, especially in the Middle East and Asia, anxious to deflect their own responsibility for the discontents of their restive subjects. But traces of its influence, alongside solemn asseverations of its real, actual truth, can also be found today, in our own turbulent times, among some of the unlikeliest bedfellows in the enlightened West.

To approach the mystery of its longevity, let’s begin by exploring its history.

I. A Blueprint for World Domination

In 1903, a slim volume appeared in Russian titled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. It was purportedly based on the report of two accidental eavesdroppers: a German scientist named Dr. Faust and a shadowy convert from Judaism named Lassalle (perhaps to be identified as the German-Jewish socialist but anti-Marxist Ferdinand Lasalle, who died in 1864).

The year, we learn, is 1860, and the two men happen to overhear a speech given by an elderly rabbi at a clandestine meeting. It emerges that such secret gatherings have been held once every 100 years. At them, emissaries from each of the twelve tribes of ancient Israel discuss, refine, and perfect their strategy of Jewish world domination.

In the course of this particular meeting, the delegates review 24 plans, or “protocols,” in all. The occasion ends with the rabbi’s speech, at whose climax the assembled conspirators proclaim that “our domination will take place when all of the world’s gold will be in our hands, for gold is the New Jerusalem.”

At least, that is how the standard version goes; over the years, the Protocols would appear in many editions, many versions, and many languages. Even the title would vary—with, for instance, “Elders of Zion” given as “Learned Elders of Zion” or “Sages of Zion.” Indeed, although the 1903 edition appears to be the one on which subsequent versions and translations were based, each exhibiting its own degree of fidelity to the “original,” it is likely that the Protocols were first composed earlier, in the 1890s.

Here, from Protocol 10, “Preparing for Power,” is a representative excerpt, as rendered in the 1918 English version of this “blueprint for the domination of the world by a secret brotherhood” (as the preface has it). The unnamed speaker, presumably the leader of the cabal, having previously traced the history of politics from earliest human times through to the age of the modern liberal state—itself posited to be a vast ruse concocted by the plotters to deceive the “mob” and the “goyim”—is discoursing on where and how to proceed from here:

When we introduced into the state organism the poison of liberalism, its whole political complexion underwent a change. States have been seized with a mortal illness—blood-poisoning. All that remains is to await the end of their death agony.

Liberalism produced constitutional States, which took the place of what was the only safeguard of the goyim, namely, despotism; and a constitution, as you well know, is nothing else but a school of discords, misunderstandings, quarrels, disagreements, fruitless party agitations, party whims—in a word, a school of everything that serves to destroy the personality of state activity. . . .

Then it was that the era of republics became possible of realization; and then it was that we replaced the ruler by a caricature of a government—by a president, taken from the mob, from the midst of our puppet creatures, our slaves. This was the foundation of the landmine which we have laid under the goy people—I should rather say, under the goy peoples. . . .

In order that our scheme may produce [the desired] result, we shall arrange elections in favor of such presidents as have in their past some dark, undiscovered stain, some “Panama” or other. Then they will be trustworthy agents for the accomplishment of our plans, out of fear of revelations and from the natural desire of everyone who has attained power, namely, the retention of the privileges, advantages, and honor connected with the office of president. . . .

The president will, at our discretion, interpret the sense of such of the existing laws as admit of various interpretation; he will further annul them when we indicate to him the necessity to do so; besides this, he will have the right to propose temporary laws, and even new departures in the government’s constitutional working, the pretext both for the one and the other being the requirements for the supreme welfare of the state.

By such measures we shall obtain the power of destroying little by little, step by step, all that at the outset, when we enter on our rights, we are compelled to introduce into the constitutions of states to prepare for the transition to an imperceptible abolition of every kind of constitution, and then the time is come to turn every form of government into our despotism.

And so it proceeds, in minute detail, turgidly, relentlessly, mind-bendingly onward.

Clearly, all of this elaborate and sophisticated-sounding ratiocination, of whose intricacy I’ve been able to convey the merest hint, is the work of an extremely fertile imagination, or more likely of several imaginations—to judge by the weird shifts in tenses in even this one abbreviated passage, not to mention the sudden allusions to contemporary events like the French Panama Canal scandals of 1892-93. None of which, however, stopped the Protocols from becoming one of the most famous and most widely devoured literary products of modernity. Over the decades, it found and has continued to find avid promoters and readers all over the world, from Japan to India, from the Arab and Muslim Middle East to Europe both East and West, from Britain and the United States to Russia and beyond. It has provided scripts for radio and TV shows and movies, been serialized in newspapers (including, in 1938 in the U.S., Father Coughlin’s Social Justice), adapted in spinoff publications (including Henry Ford’s Americanized version, The International Jew, which appeared in installments in the 1920s), invoked as an authoritative source in political documents like the 1988 covenant of Hamas (“[the Zionists’] plan is embodied in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion”), and distributed as textbook material throughout the Arab and Islamic world.

Nowhere, of course, did the work achieve greater popularity or attract more devoted fans than in early 20th-century Germany, being cited as an authentic source by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf and by the Nazi publicist Alfred Rosenberg in a book explaining “Jewish world policy.” Once the Nazi party came to power in 1933, it was reprinted and disseminated in multiple editions and in millions of copies during the years leading up to World War II.

II. Theories of Authorship

At the hands of an army of scholars, government commissions, and investigative journalists, the Protocols’ inauthenticity has been demonstrated many times over. But what do we know about how it came into being? In fact, its authorship, even today, remains a mystery, with new revelations or at least new theories seeming to surface every ten years or so.

One lifelong scholar of the Protocols and related works is the German historian Michael Hagemeister, who has just edited and published a huge new collection of documents under the title Die “Protokolle der Weisen von Zion” vor Gericht (“The Protocols of the Elders of Zion before the Court”). The book deals with trials that took place in Berne, Switzerland between 1933 and 1936 as a result of legal action brought by local Jewish communities against the publisher of the work’s Swiss edition. In addition to the text of the proceedings themselves—the lawsuit was based on the contention that publication of the Protocols violated a constitutional ban on incitement to hatred—the volume includes a variety of other relevant documents as well as extensive annotations, commentaries, and a long introduction by Hagemeister himself.

The particulars of the Berne trials need not detain us. Suffice it to note that, where the authorship of the Protocols is concerned, neither the vastly learned Hagemeister nor any other investigator has reached a satisfying conclusion, though a number of perennial candidates have been ruled out. Thus, a Russian named Sergei Nilus was probably the editor of the 1905 edition, and possibly of the 1903 original as well. But, despite the persistent claims of some, he could not have been the author. Even the conflicting accounts of his life—a priest, a professor, a man with three wives, a rival to Rasputin—have been shown by Hagemeister to be fantastical.

A similar story can be told about Pyotr Rachkovsky (d. 1910), the head of foreign operations for the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, and later head of the entire force, whom many historians have named as the author. In one accepted view, he commissioned the Protocols’ creation and enlisted Nilus, or the right-wing journalist Matvei Golovinskii, or some otherwise unknown person, to produce the forgery. But here, too, Hagemeister and others have shown that the evidence for Rachkovsky’s involvement is flimsy at best, and for Golovinskii’s even weaker.

Rachkovsky is also reputed to have commissioned the faking of a letter by the revolutionary Georgy Plekhanov, who was Lenin’s predecessor as head of the Russian Social Democratic party. According to the letter, another left-wing Russian leader had been secretly collaborating with Britain’s intelligence service. Like much of what the Okhrana did, this supposed product of Rachkovsky’s pen would have been intended to discredit socialists and sow dissent in their ranks.

With that in mind, is it not tempting to speculate that, if not Rachkovsky himself, elements of the tsarist regime might also have produced the Protocols as a way of harnessing anti-Semitism as a political weapon? After all, there can be little doubt that, as the above excerpt suggests, whoever did compose the work intended to discredit liberalism, in even its most moderate forms, as a Jewish plot. Yet this does not necessarily mean that the Okhrana had a role in producing it, and even if such a role were definitively determined, we would still be left with only speculation as to its primary motive. Needless to add, such speculation exists in abundance, most of it tying the forgery to high-level power struggles within the Russian government.

The truth is that the contents of the Protocols themselves invite conflicting theories about their origins. After all, the work purports to contain a super-secret document that, having been obtained by a person or group at an unknown date, has felicitously fallen into the hands of an editor. One version states that the Protocols originally existed in oral rather than written form. Another claims the document had its origins in Solomon’s Temple, built 3,000 years ago, when the original cabal, then known as the Sanhedrin—a term that in reality didn’t come into use until much later than the destruction of Solomon’s Temple—first met; it was only in the second half of the 19th century that one or more persons are said to have successfully eavesdropped on the centennial meeting in Prague and were then able to deliver a report to the publisher.

Even the 1918 English translation poses a puzzle. The London Morning Post, which published it in nineteen installments, attributed the translation to one Victor Marsden, allegedly a British citizen working for a firm that operated in Russia. Unfortunately, it is entirely possible that he, too, is a fictional character.

There is a lesson in all of these dead ends. Many years ago, having joined the long list of investigators into the source and authorship of the Protocols, I had a conversation with the late Norman Cohn, whose 1967 Warrant for Genocide remains the chief scholarly study of the subject, or at least did until Hagemeister’s more recent efforts to supersede it. After a morning spent in the basement archives of the institute in London that I headed at the time, Cohn emerged to issue a dire warning: “Walter, beware: preoccupation with this kind of idiotic paranoia—it’s infectious.”

At the time I made light of his friendly advice. But within a few years I began to realize that not only was this document a paranoid conspiratorial undertaking in itself but so, too, was the search for the fabricators. There is a real danger of investing too much time and mental energy to achieve certainty where true, total certainty is unobtainable. Even in the best of cases, history is not an exact science. Where the Protocols in particular are concerned, it is certain that they are a forgery, but we shall probably never know who wrote them. A forgery can succeed only if the identity of its author or authors is kept hidden, and those behind the book’s lies sought above all to conceal their identities—and succeeded. If they were affiliated with the Okhrana, they were true professionals.

Inquiries into the authorship of the Protocols are thus bound to disappoint—but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to be learned about its origins. A more fruitful angle by which to approach this issue may be that of literary history. In other words, instead of asking about the work’s direct authorship, ask about its background: what do we know about the social and especially the literary context in which it took root?

III. Enter Hermann Goedsche

In the 19th century, a new genre appeared in European literature: the political-conspiracy novel. Rapidly gaining popularity, it influenced other literary forms as well. Its precursors were the works of the French writers Eugène Sue—author of the then-wildly popular The Mysteries of Paris—and the much better remembered Alexandre Dumas, whose many novels include The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, both originally published in serial form, as well as The Queen’s Necklace and other favorites.

An early pioneer of the conspiracy novel, and of the historical-political novel more broadly, was Hermann Goedsche (1815-1878). He might even be considered the genre’s founder. A native of Silesia and a man of strong right-wing convictions, he wrote under several different pen-names and was also active as a provocateur in the pay of the Prussian police. In his journalistic career, he contributed to the same far-right wing publications as did Otto von Bismarck. Once he even participated in a Rachkovsy-esque forgery.

In one chapter of his 1868 novel Biarritz—published under the pseudonym Sir John Retcliffe—Goedsche describes the meeting of a secret rabbinic cabal very much like the one described in the Protocols. As in many versions of the latter work, the gathering takes place in the Jewish cemetery in Prague. The climax of the scene is the speech in which the rabbi who has chaired the meeting outlines the methods to be used in the quest for world domination: to acquire as much real estate as possible, to transform craftsmen and artisans into industrial workers, to infiltrate fellow Jews into high finance and public office, to spread democracy and undermine the social order, to seize control of the media in order to manipulate the mob, and, ultimately, to elevate the president of the Council of World Jewry to the position of ruler of the world.

The parallels with every known edition of the Protocols, parallels not just of content but of language, are too many to ignore; a number are on display in the brief excerpt I presented earlier.

This isn’t to say, however, that the story of the Protocols starts with Goedsche. The rabbi’s speech, as many have pointed out, bears an overwhelming resemblance to a scene from an 1864 novel by the French author Maurice Joly imagining a dialogue in hell between the philosophers Niccolò Machiavelli and Montesquieu. Ironically, Joly’s novel was not anti-Semitic at all but, rather, a satirical attack on Napoleon III by a defender of liberalism (i.e., Joly) against authoritarianism.

There’s little doubt that Goedsche lifted the passage directly from Joly: he was a devoted reader of French literature and an avid plagiarizer. In fact, he baldly borrowed from Dumas’s The Queen’s Necklace for an earlier part of the same chapter in Biarritz.

But from there the plot thickens. In 1872, four years after the publication of Biarritz, the rabbi’s speech was published in Russia as a stand-alone pamphlet. But now, unlike Biarritz, which never purported to be anything other than a work of fiction, the pamphlet claimed the speech was authentic. Versions of it then appeared later in Paris and Prague and, in 1887, in Germany.

When the historical veracity of the Protocols was still considered a legitimate question, its defenders often pointed, however absurdly, to the rabbi’s speech as evidence. The likelier scenario is that one of the several stand-alone pamphlets taken from Goedsche’s work was transmuted into the earliest version of the Protocols. Who wrote that first version, and what were the intermediate steps between it and the Protocols we know today, are, to repeat once more, questions unlikely ever to be answered.

For our purposes, in any case, the salient point is that although prototypes of the Protocols floated around Europe, none of them enjoyed or would ever enjoy the Protocols’ mass appeal. Why not?

IV. Timing Is All

In addressing that question, it’s worth comparing Goedsche with another 19th-century German author of popular fiction who was likewise fond of pseudonyms and plagiarism. This was Karl May (1842-1912), who also happened to be a devoted reader of Goedsche, modeling his Die Juweleninsel (“The Isle of Jewels”) on the former’s Nena Sahib.

May’s chosen genre, however, wasn’t conspiratorial fiction but the adventure story. Moreover, while Goedsche’s books were a modest success, May’s became a sensation: he was probably the most successful German writer of his time. Few Central European readers living between 1900 and 1950, especially among the younger generations, would have been unfamiliar with his characters. His prominent devotees included both Adolf Hitler and Albert Einstein.

Enormously prolific, May is known to have written some 70 works under both his own name and pseudonyms, and no doubt even more under pen-names yet to be definitively connected with him. Most of his stories are set in the Middle East, the American Wild West, and a few other exotic parts of the globe. The hero of the Westerns, the American hunter Old Shatterhand, also appears in the Middle Eastern novels as the T.E. Lawrence-like Kara ben Nemsi. In both sets of books he has a native sidekick: respectively, Winnetou and the comic-yet-sympathetic Hadschi Halef Omar.

There are certain similarities between Goedsche’s novels and May’s, but the disparities are greater and worth specifying. Goedsche’s novels are heavily political, anti-Semitic, and peppered throughout with anti-British propaganda. By contrast, May’s are by design consistently apolitical. One would be hard-pressed to find in them any mention whatsoever of Jews or Judaism, and they contain not a whit of anti-Semitism. Indeed, although they would be considered scandalously politically incorrect today, they present a generally positive, if somewhat romanticized, picture of non-European peoples. The heroes of the Westerns are the proud and honest Apaches, the villains the perfidious Comanches. In the Middle Eastern novels, Bedouin take the place of Apaches.

I bring up May not just because of my fond recollection of reading his work as a youth, but because consideration of his work next to Goesdche’s points to the influence of that mysterious social force called fashion, which operates in literature as infallibly as in dress. Why did May’s novels, free of anti-Semitism, wildly eclipse Goedsche’s in popularity? The answer may be linked to time and place. After all, the Prague cemetery scene was also readily available from 1868 on, but failed to gain traction until the 20th century, and the rabbi’s speech, although first published in German, appeared in pamphlet version only as a translation into German from Russian and was then displaced, almost completely, by translations of the later 1903 version.

In other words, the Protocols came to Germany from Russia, and not the other way around. How they arrived is the subject of a field of study in its own right. Some theories posit that the Protocols “escaped” Russia and came to Western Europe via the “Baltic barons”—semi-Russified German nobles, mostly from Latvia, who allied themselves with the tsar when their territory came under Russian rule in the 18th century. After World War I many of these aristocrats, disenfranchised by the newly declared independence of the Baltic states, settled in Germany and brought with them a strain of virulent anti-Semitism. Their role in the shaping of Nazi ideology is a worthy topic of investigation, but about their role in relation to the Protocols, little, if anything, can be said with confidence.

What does seem undeniably plausible, to return to literary history, is that, at some point, the Western mass audience for anti-Semitic conspiracy theories grew considerably. Consider: only after World War I did the Protocols gain their immense influence, spreading from Russia to Western Europe and then to America. The English translation, as I mentioned earlier, appeared only in 1918, whereupon it received enormous attention in the press. Supposedly, Winston Churchill himself wrote an article in which he endorsed their content in 1920. (I say “supposedly” because more than a few articles attributed to Churchill were heavily modified by others or were even sheer forgeries).

This was a time when all kinds of allegations and revelations bobbed to the surface concerning the secret forces behind the various political, social, and economic upheavals of the war years and their aftermath. The reasons are not particularly mysterious. World War I was a tremendously disorienting event, and nearly every country touched by it emerged from the encounter transformed. Not least, the war shook ordinary people’s faith in settled institutions and those highly regarded personages in charge of them who had proved themselves to be completely incompetent. (See the quip about the wartime British army having consisted of “lions led by donkeys.”)

In Russia, from the get-go, the military began hunting up excuses for its own catastrophic failures, pointing to everything from a shortage of ammunition to espionage, or to the former as caused by the latter, which almost immediately became identified with Jews. As S. An-sky describes in his magisterial chronicle of Russian Jewry’s wartime fate, absurd conspiracy theories about Jewish machinations emerged from townspeople, local peasants, and the troops themselves, providing a tailor-made self-exculpatory narrative for the generals—who proceeded to wreak brutal vengeance on Russian and Polish Jews.

Germany was not much better. While the German anti-Semites of the 1880s had failed to form a popular political movement, in 1916 they hit on a magic formula in the form of alleged Jewish war profiteering as an explanation for hardships on the home front. By 1918, this had morphed into the notorious stab-in-the-back myth that the war had been lost not because the Kaiser’s army was outgunned and outmaneuvered on the battlefield but because of sabotage by perfidious Jews and (what came to the same thing) socialists. As with other contemporaneous myths, this one succeeded because, at the time (and not just because senior officers had hidden the truth from politicians and the public alike), it seemed to solve an otherwise bewildering puzzle: until the spring of 1918, Germany seemed to be winning. What else could explain its sudden defeat?

Of course, Jews were not the only villains in such outlandish conspiracy theories, which flourished during the war and after. The literary historian Paul Fussell documents an abundance of them that circulated among British and American troops on the front lines, none of which involved Jews. In the Ottoman empire, defeats in the Caucasus were blamed on Armenian perfidy. By 1916, even much of the Russian public had moved on from anti-Semitic libels to feverish rumors about Rasputin, or the disloyalty of the tsarina, who herself was a German princess.

On the other hand, Nicholas II spent the last weeks of his life excitedly reading passages from the Protocols to his family in a makeshift Bolshevik prison. A year later, royalist insurgents were massacring Jews in unprecedented numbers. Among White Russians fleeing the Bolsheviks in the early 1920s, a number who ended up in France and Germany were carriers of anti-Semitism and disseminators of the Protocols, as Hagemeister reminds us in his introduction to the volume on the Berne trials.

As for what would transpire in the ensuing years in Germany itself, no reminders are necessary.

V. The Return of The Protocols?

And now here we are again, in a mini-revival of our own, with a small but influential number of sophisticated-seeming Western politicians and intellectuals eager to explain to us how, in the otherwise head-turning welter of recent events and defeats—from abrupt crises in our economic systems, to reversals of Western and especially American power abroad, to terrorism reaching our own shores—a single, all-seeing cabal can be identified manipulating our politics, our society, even our brains.

Some of the politicians and intellectuals marketing these explanations are bold enough to name the hidden enemy as, in one word, the Jews, either explicitly or through the use of code-words like “Zionists” or “neocons” or “the Israel lobby.” In doing so, some, on both the left and the right, have appealed for their authority to the canonical source of, no less, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. A few, Jews themselves, turn and point an accusing finger at their own people (and thereby resuscitate another unpleasant human type).

A few examples must stand in for the rest. Prominent on the left include many who advertise themselves as heroic truth-tellers against Jews and Zionists all too ready to label any critics of Israel, or supporters of Palestinians, as anti-Semitic. Among them, in Great Britain—as David Hirsh meticulously documents in Contemporary Left Anti-Semitism—are Ken Livingstone, the former mayor of London, Jenny Tonge, a Liberal Democrat member of the House of Lords (“the pro-Israeli lobby has got its grips on the Western world, its financial grips”), and the current leader of the Labor party, Jeremy Corbyn. Among them, too, is the anti-Israel, anti-Jewish Israeli Jew Gilad Atzmon, who writes: “American Jewry makes any debate on whether the Protocols of the Elders of Zion are an authentic document or rather a forgery irrelevant. American Jews (in fact Zionists) do control the world.”

On both the left and the right, conspiracy theorists constantly invoke The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy (2007) by the American political scientists John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt. The book notoriously holds “the lobby” responsible in particular for pushing the U.S. into the 2003 war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq. But, as Hirsh writes, its sweeping categories and its suggestion of covert powers working to promote policies inimical to the country’s interest inevitably echo such earlier anti-Semitic staples as Hitler’s blaming “Jewish financiers” for World War I, Charles Lindbergh’s claims that American Jews used their power to draw the U.S. into World War II, and the Internet meme that the 9/11 attacks were engineered by the Mossad.

The Mearsheimer-Walt book, and the subsequent reflexive characterization of its critics as, in effect, agents or tools of an all-powerful “lobby,” have become touchstones of the recent recrudescence of what might be called the higher Western anti-Semitism. Which is not to say that updated versions of the old-fashioned or lower variety, some expressly invoking the Protocols, are lacking on either the left or the right.

All of this suggests that an attraction to conspiracy theorizing in general, from whichever point on the political spectrum, can lead ineluctably to an attraction to the most venerable and longest-licensed conspiracy theory of them all, about the most conspicuous and traditionally vulnerable group of them all. If the history of the reception of Goedsche and the Protocols tells us anything, it’s that in these turbulent times, no one should be surprised, and that all who care for the honor of the Jews, and for the truth, should be prepared.

The author is grateful to Harry Hoshovsky for invaluable help in researching and writing the present article. He also extends thanks to Christopher Wall.

More about: Anti-Semitism, Europe, European Jewry, History & Ideas, Protocols of the Elders of Zion