At the end of her sweeping probe into the normalization of anti-Semitism on American campuses, Ruth Wisse lays down a double challenge. Can the United States, the world’s pre-eminent liberal democracy and the one most exceptionally hospitable to its Jewish minority, retain that exceptional status “by recognizing the threat [posed by contemporary anti-Semitism] and fighting it off?” For their part, can American Jews, by gathering their mettle, help this country’s universities “heal themselves of this most deadly pathology?”

In fact, the challenge is not just national but global. What happens in America will determine whether the Jewish people can maintain a center of power and influence in the Diaspora as well as in the sovereign state of Israel. At this critical juncture, as Wisse acknowledges, American Jewish political power, if it is to be effective, needs to be not just nursed but projected. The turmoil of recent years has been bruising: alongside the campus crisis and BDS, we have seen America’s bilateral relations with Israel collapse, in tandem with an assault of unprecedented scale against the “Israel Lobby,” a hydra-headed creature whose efforts to derail American foreign policy were menacingly portrayed in a 2007 book of that name by the political scientists John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt.

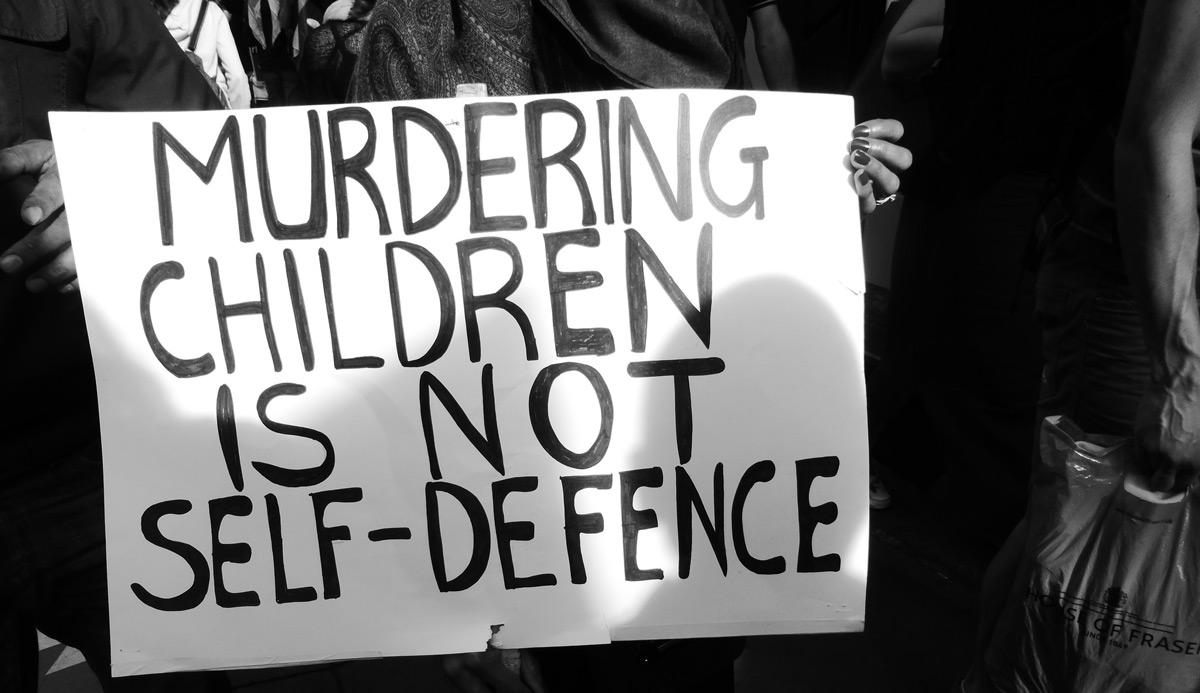

As Wisse shows, anti-Semitism in American universities is channeled through the demonization of the state of Israel, which concretely gets expressed through the intimidation, rhetorical and sometimes physical, of Jewish students. Much of the blame for allowing this state of affairs to fester lies with university administrators who, decking themselves in the garb of free speech, “tolerate, however squeamishly,” campaigns “to undo the Jewish homeland and to demonize the already most mythified people on earth.”

It may be useful to remember that this is not an altogether new story—even in America. In the 1930s, as Europe entered its darkest age, university administrators impeded efforts to find departmental posts for German Jewish academics fleeing Hitler. According to Stephen H. Norwood in The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower, there was already “a longstanding tradition in American colleges and universities of excluding Jews from their faculties,” a tradition then exacerbated by “administrators’ unwillingness to appoint refugees to anything but very short-term positions.” Simultaneously, university authorities were content to tolerate both agitation on behalf of, and apologetics for, the Nazi regime in Berlin. In June 1933, an alarmed Anti-Defamation League asked its academic contacts to “transmit [any] information they gathered” about German exchange students spreading “extremely destructive” Nazi propaganda on American campuses.”

Inevitably, the problem extended to faculty as well. German departments and German campus clubs played a key role in assisting the Nazis, in the words of a May 1935 report in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, “to inject the Hitler virus into the American student body.” Just as insidious were apologists for the Nazis who cautiously distanced themselves from the violent assaults by Brownshirt thugs on Jews and others while insisting that the German regime was essentially a rational actor deserving of respect. In this connection, Norwood highlights the efforts of the Institute for Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, whose professors assured Americans that Hitler’s seizure of power was caused by the “unfair conditions” imposed by the Allies in the Treaty of Versailles. In an article submitted to the New York Times, he notes, a history professor at Smith College purred that the restrictions imposed on Jews in April 1933, which included their expulsion from professions like medicine and law, were “relatively moderate.” (In a rare moment of institutional honor, Lester Markel, who ran the Times Sunday edition, turned the piece down.)

Rationalizations like these will be familiar to anyone today who has read the efforts to downplay the eliminationist cries of Iran (or Hamas, or Hizballah) as so much rhetorical bombast. But there’s an important difference. In the 1930s and 40s, by contrast to the present, strong general hostility to Jews was a serious factor in America. In a 1938 survey, 41 percent of the American public agreed that Jews possessed too much power. By 1945, that figure had risen to an astonishing 58 percent. In a separate survey that same year, even as victory in Europe beckoned, 23 percent of respondents answered that they would be influenced to vote for a candidate for Congress should he “declare himself as being against the Jews.”

By any measure, public opinion is vastly more benign today, and has been consistently benign, with only occasional and temporary dips, for decades. American society, as Wisse writes, “seems free—solidly free—of the anti-Semitism that infects American universities.” But there is that exception: in the elite precincts of colleges and universities, in the media and the publishing world, in many churches and in many policy circles, the ground has shifted dramatically. Which raises the question: given the influence of these sectors, how long can society at large remain resistant to the plague?

The answer to that question will not be revealed, at least not yet, in survey data. In the past, polling tended to focus on non-Jewish attitudes to Jews as Jews, thereby providing an accurate record of feelings about such conventional anti-Semitic tropes as, for example, Jewish avarice or Jewish clannishness. In our time, when anti-Semitism crystallizes around detestation of Israel, there is a need to explain, in the teeth of bitter opposition, why the phenomenon under investigation deserves to be called anti-Semitism at all.

This brings us to something that Wisse has written about elsewhere: the widespread accusation that Jews or others who raise concerns about the virulence of the anti-Israel mood are “playing the anti-Semitism card.” “Anyone who criticizes Israeli actions or says that pro-Israel groups have significant influence over U.S. Middle East policy,” complained Mearsheimer and Walt in The Israel Lobby, “stands a good chance of getting labeled an anti-Semite.” As they saw it, American Jews and their leaders, not content with perverting the proper aims of U.S. foreign policy, were also silencing honest criticism by calculatedly smearing the motives of the critics.

This, too, is an old trick: even that out-and-out anti-Semite Henry Ford harrumphed at having “to meet the degrading charge of ‘anti-Semitism’ and kindred falsehoods.”

An old trick, yet still a reliable one—and therein has resided perhaps the greatest difficulty when it comes to responding to Wisse’s dual challenge. The scholar David Hirsh, writing about the boycott campaign launched in British universities, observes that it “sought to protect itself against a charge of anti-Semitism by including clauses in its boycott motions which defined anti-Semitism in such a way as to make its supporters not guilty.” The same tactic was enshrined in a motion passed in 2003 by the Association of University Teachers (AUT), a British labor union representing academics:

Council deplores the witch-hunting of colleagues, including AUT members, who are participating in the academic boycott of Israel. Council recognizes that anti-Zionism is not anti-Semitism, and resolves to give all possible support to members of AUT who are unjustly accused of anti-Semitism because of their political opposition to Israeli government policy.

Similar arguments are deployed in America, too, including by anti-Zionist Jews. Currently, promoters of BDS in Indiana are seeking signatures for a petition that cites “the Torah values of justice,” no less, as being in complete harmony with the action of boycotting the Jewish state.

But, thankfully, that’s not the end of the story. The pro-BDS petition in Indiana was itself launched to protest a bill by Indiana’s state legislature declaring that body’s forthright “opposition to the anti-Jewish and anti-Israel” BDS movement. And the Indiana bill went even farther, decrying today’s global escalation of anti-Semitic speech and violence as “an attack, not only on Jews, but on the fundamental principles of the United States.” Finally, the bill expressed the legislature’s gratitude to the presidents of Indiana University and Purdue University for their own strong condemnation of the academic boycott of Israel.

The Indiana bill came nine days after a similar measure was passed by Tennessee’s state legislature. That resolution denounced the BDS movement as “one of the main vehicles for spreading anti-Semitism and advocating the elimination of the Jewish state. . . [and] undermin[ing] the Jewish people’s right to self-determination, which they are fulfilling in the state of Israel.”

The Indiana and Tennessee bills were passed following an active campaign by local Jews and their allies, including a large contingent of Christian pro-Israel advocates. In light of Wisse’s challenge, they are valuable for several reasons. First, the legislators’ unanimous support for the bills underlines the abiding affection with which large numbers of Americans regard Israel. Second, the bills were the product of activism at the local level—the very same political space in which the BDS movement has chalked up a slew of minor victories. Third, the bills amount to a policy guide for professional associations, voluntary groups, and other civil-society organizations faced with demands to endorse the boycott. Instead of allowing BDS advocates to define the issues on their own terms, these bills oblige them to explain first why and how they are not, in fact, trafficking in an especially devious mode of anti-Semitism.

Above all, the passage of the two bills neatly demonstrates the rightness of Wisse’s stress on America’s potential to exercise wisely and forcefully its exceptional clarity on the issue of anti-Semitism. American Jewish organizations would be well advised to take the hint, and to begin promoting similar measures in other states with the goal of isolating the boycott movement and forcing it onto the defensive.

In an earlier contribution to Mosaic, I argued that anti-Semitism in Europe had adopted the characteristics of a social movement, seeking a fundamental shift in beliefs and behavior with the aim of reaching a critical mass of opinion hostile to Jews. In practice, such shifts are achieved by transforming contentious propositions (for example, that Israel is an “apartheid state”) into commonsense axioms that are then reinforced by opinion-forming institutions like universities.

But there is no good reason why the process can’t be turned on its head, and even turned around, by groups prepared to seize the initiative, perhaps by taking the wins in Indiana and Tennessee as a point of departure. Defeating anti-Semitism necessarily entails, as a first step, exposing the denial of anti-Semitism that enables anti-Zionism to portray itself as considered speech and not as hate speech.

Ruth Wisse is to be applauded for the great lucidity of her own understanding that the fight against anti-Semitism is also a fight for the soul of our century, and that winning it will require a creative fusion of political influence and political imagination. The success of such a counteroffensive will be measured, both on and off campus, by how it affects assumptions and emotions about the Jewish state and the Jewish national movement that created it. Like Wisse, I hope that the American Jewish community, with the help of its myriad non-Jewish friends, will rise to the challenge.

More about: Anti-Semitism, Anti-Zionism, BDS, Israel & Zionism, Politics & Current Affairs