Seventy years ago, on April 24, 1950, the parliament of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan resolved in favor of “complete unity between the two banks of the Jordan, the eastern and western, and their union in one single state.”

Two years earlier, in the first Arab-Israeli war, the military legions of Jordan’s King Abdullah had occupied the West Bank and had held their ground until signing an armistice with Israel in April 1949. Even earlier, Abdullah had taken a series of steps to unify the two banks—or, more precisely, to annex the West Bank to his existing kingdom. His 1950 “unification” of the two banks would last until the Six-Day War in June 1967.

Among Israelis, it has long been customary to dismiss Abdullah’s act as illegal, and to emphasize that, internationally, only Britain (or only Britain and Pakistan) ever recognized it. The invading Arab states in 1948, said Israel’s UN ambassador Chaim Herzog in 1977, “could not acquire rights of sovereignty over the territories they occupied,” and were “without any authority unilaterally to annex” them. Therefore, “Jordan’s unilateral ‘annexation’ of Judea and Samaria in 1950 . . . had no basis or validity in international law” and indeed “never received any international acknowledgement.”

Yehuda Blum, another Israeli UN ambassador, wrote the same. At best, he argued, Jordan had enjoyed the rights of a belligerent occupant of territory captured by aggression. But that only meant that its “purported annexation of Judea and Samaria was invalid from the outset and certainly devoid of all legal effect after that.”

In retrospect, though, and leaving aside the legal merits of the case, Abdullah’s “unification” was, politically speaking, one of the smoothest and best-choreographed annexations in modern history. Although the two banks failed to achieve cohesiveness or harmony between them, within a couple of years few actively questioned their “unification.” That included Israel: the arguments raised by Herzog and Blum came to the fore only after 1967, when Israel itself possessed the territory and sought to undermine any residual Jordanian claim to it.

And today? No one dwells on the 1950 “unification” because it became moot: in 1988, Jordan effectively gave up any claim to the West Bank. By that time, as Judea and Samaria, it had been under Israeli rule for longer than it had been the West Bank of Jordan.

Still, the way in which Abdullah prevailed, the foreign recognition he secured, and the price he ultimately paid for annexation may hold some lessons for Israel today as it thinks to go down its own road of annexation. When he made his move, Abdullah enjoyed no fewer than ten advantages, none of which can be replicated by Israel. But Abdullah did have one additional advantage that present-day Israel shares with him; at the end of this essay I’ll consider whether it outweighs all of Israel’s comparative disadvantages.

In what follows, I use the word “annexation” as a shorthand. In 1950, Jordan used “unification.” Israel now speaks of “applying sovereignty.”

A quick grab

Abdullah’s first advantage: unlike Israel after 1967, he didn’t wait 53 years before acting. As soon as his army entered the territory in May 1948, he appointed military governors to administer it. In October 1948, he convened a meeting of Palestinian Arabs, mostly refugees, in Amman, where they pleaded to be ruled by him. In December, a conference of West Bank notables in Jericho called for unification of both banks under the king’s rule.

The conclusion of the April 1949 armistice with Israel accelerated the process. In December of that year, a law allowed “Arabs of Palestine” to claim Jordanian nationality. In March 1950, “West Jordan” became an official administrative unit. In April, Jordan held parliamentary elections on both banks. The new parliament, made up equally of East and West Bankers, finalized the unification.

The whole thing was thus a done deal in just under two years after the termination of Britain’s Mandate in Palestine. There have been faster annexations in history, but few have been so carefully staged, each step building legitimacy for the final act. That Abdullah moved with such deliberate speed reflected the plain fact that he was an absolute monarch who’d made up his mind.

By comparison, Israel’s position over the same territory has been a prolonged muddle, reflecting Israel’s own character as a democracy that is not of one mind but of many minds. True, concerning eastern Jerusalem, with the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, and the old Jewish Quarter, there were few doubts, and Israel annexed it almost immediately in June 1967. (The deed was later fortified by the Knesset’s “basic law” on Jerusalem, passed in 1980 and amended in 2000.) But for five decades it has administered the rest of the West Bank as occupied territory de facto (though not de jure) under a military administration and subject to the humanitarian provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

While Israel has claimed to do all of this without prejudice to its own rights to the “disputed” territory, in 1993 it also signed a Declaration of Principles with the Palestine Liberation Organization that undercut those claims. The international lawyer Alan Baker, a former Israeli ambassador and no leftist, has explained the consequences:

It’s impossible to annex a disputed territory unilaterally. We’ve already applied personal law to the [Israeli] settlers. They are subject to the Israeli criminal code and they pay income tax. We can’t go beyond this unless it becomes ours as part of an agreement. We undertook in Oslo that they [the Palestinians] would not become a state and [would not] try to be admitted to the UN, and that we would not annex. The whole fate of the territories is subject to negotiations. That’s what we signed.

In the course of these 53 years, Israel’s standing in the territory has become so encrusted with practices, agreements, legal rulings, tacit understandings, and precedents that any move toward unilateral annexation, even if only of a part of the West Bank, would appear to be a sharp departure from the status quo that Israel itself constructed.

Abdullah did not tie himself in knots. Israel has done so over decades, and they’re so numerous that they can’t easily be undone in one fell swoop.

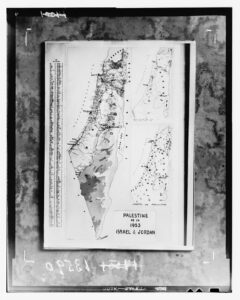

The second advantage enjoyed by Abdullah was that he already had a map: the one attached to the April 1949 armistice agreement with Israel. Representatives of Israel and Jordan had signed this map in the presence of the United Nations mediator Ralph Bunche. (Moshe Dayan’s signature appeared on behalf of Israel.) The armistice line was drawn in crayon, leaving plenty of room for disputes where the crayon had been laid on thickly. But it was a line all the same, and Abdullah simply annexed the territory on the Arab side of it.

In addition, the map had already been published a year earlier, so that when Abdullah annexed the “West Bank,” people around the world could imagine its shape and location in their mind’s eye. Today, even though the armistice line has long since disappeared on the ground, it’s still a (cramped) dotted line on most of today’s maps of the Middle East.

Israel, too, could conceivably annex up to an existing line: namely, the Jordan river, the administrative and later the political border between mandatory Palestine and Transjordan. While no border is truly “natural,” the river passes through one of the most striking topographical features of the Middle East, running as it does through the middle of a deep, arid rift.

But drawing a border only at the Jordan would leave millions of Palestinian Arabs in Israel. There is apparently no government in the world, including that of Israel’s “best friend ever” in Washington, that would welcome annexation of everything west of this line.

So Israel and the United States are now in the process of producing a new map, laying out the areas of the West Bank that Israel might annex at some indeterminate point, depending on the circumstances, leaving the rest to a prospective Palestinian state.

That map isn’t finished, but one thing is clear: the proposed border between Israel and the projected Palestinian state won’t look like any other border in the Middle East, or perhaps in the world. Stretching hundreds of miles, it will wind around so many enclaves and connecting roads that few people outside Israel will be able to hold it in their mind’s eye. Each twist will make it look less “natural,” and therefore less permanent.

Israelis used to complain that the 170-mile-long armistice line drawn in 1949 was tortuous and indefensible. But that 1949 line will look simple next to the 2020 map now being compiled. The new map will reflect the fact that Israel’s settlement policy proceeded helter-skelter, without a coherent strategic vision. Making it seem permanent would take a very long time, and even longer if it were subject to periodic revision.

And just as that map won’t be as straightforward as the one Abdullah used in 1950, it also won’t bear the signatures of both Arabs and Jews. At best, it will have only the signatures of two countries that don’t border each other: Israel and the United States.

People and territory together

Third, Abdullah didn’t fret over “demography.” Annexing the West Bank tripled the total number of people under his rule, in the process turning his original East Bank subjects into a minority. For him, it was a price worth paying. A ruler in the late-Ottoman style, he didn’t reign over a nation-state, and he didn’t think it mattered who formed the majority of his subjects. He had his Bedouin army, and that’s what kept him on top.

True, he had political opponents on the West Bank who detested him. But to all of his new subjects he was a fellow Arab, and to most of them a fellow Muslim and descendant of the prophet: a Hashemite. Many West Bankers had ties to the East Bank stretching back to the not-too-distant past when there wasn’t a Jordan separate from Palestine. Professing loyalty to Abdullah wasn’t a huge stretch. And he gave all of the West Bankers full Jordanian citizenship. That didn’t cost him much at all, because Jordan wasn’t and isn’t a democracy.

Israel can only envy Abdullah. The West Bank is now home to almost a half-million Jewish settlers, but it still has all of the Arabs Abdullah had in 1950 multiplied four times over. And Israel is the nation-state of the Jews, the solid majority of whom are not willing to add more millions of Arabs to its account.

Israel is also a democracy: its citizens, Jewish and Arab, vote and decide who rules. A large number of additional Arab citizens, most of them in favor of stripping the state of any Jewish character, would translate into greater Arab political clout. In 1950, Abdullah could take it all: the whole territory and all of its inhabitants. Today, Israel cannot.

On the fringes, it is true, Israeli voices can indeed be heard calling for annexation of heavily Arab areas or even the whole West Bank. The Arabs in the annexed territory would be offered Israeli citizenship, permanent residency, or incentives to relocate. But these proposals don’t figure in any operative plan for annexation. The reason is that the majority of Israelis don’t support them, and no friendly outside government would endorse them.

Neither, apparently, would the Trump administration. As its ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, recently put it:

Here are the facts that never go away. First is that nobody wants to establish sovereignty [over] the entirety of Judea and Samaria and provide citizenship to the millions of Palestinians who are there. Second, there is no way in the modern world that a country, especially a country as great as Israel, could possibly [be] a country with two classes of citizens, where one votes and the other doesn’t. It can’t be done.

And this connects with Abdullah’s fourth advantage. He could claim to have annexed the West Bank “based on the right of self-determination.” (That Wilsonian phrase was used deliberately in the “unification” resolution of the Jordanian parliament.) After all, the inhabitants of the territory asked to be a part of his kingdom.

Of course, there was no referendum (though a mostly elected parliament did take the final step). It was more like an acclamation in the traditional Arab style, with notables and dignitaries from towns and tribes convening and imploring Abdullah to rule over them. While much of this process had been staged by Abdullah’s minions, it provided his move with a veneer of legitimacy.

Again, this is hardly something Israel could emulate. Any annexation of territory populated by Arabs would be done against their will. A century ago, these things didn’t matter. Indeed, there would have been no Balfour Declaration in 1917 had Jewish historical rights not been given preference over the rights of the country’s “existing non-Jewish communities” (as the Declaration phrased it). But in the present world order, legal arguments and historical claims, however weighty, usually don’t trump the desires of a present-day population.

Fifth, the Arabs of Palestine in Abdullah’s day had no national leaders on the ground. The most prominent of them, the former mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, had become a wandering liability, causing mischief in Beirut, Baghdad, Berlin (under Hitler), and Cairo. No one had arisen to replace him. The West Bank itself had only local notables, and its newest inhabitants were leaderless denizens of refugee camps, living in tents. There was some resentment of Abdullah, but by and large he was walking into a political vacuum.

That’s obviously not the case today. In Ramallah, capital of the Palestinian Authority, there sit a president, a parliament, ministers, bureaucrats, police and security forces, NGOs, and even the national shrine of the tomb of Yasir Arafat. The Palestinian Authority is a government—more authoritarian and corrupt than some Arab regimes, less than others, but (almost) as much a fact as they are. Palestine is also a non-member observer state of the United Nations, and is recognized by 138 of the 193 member states.

Abdullah didn’t have to contend with Palestinian leaders who enjoyed international legitimacy. Israel does.

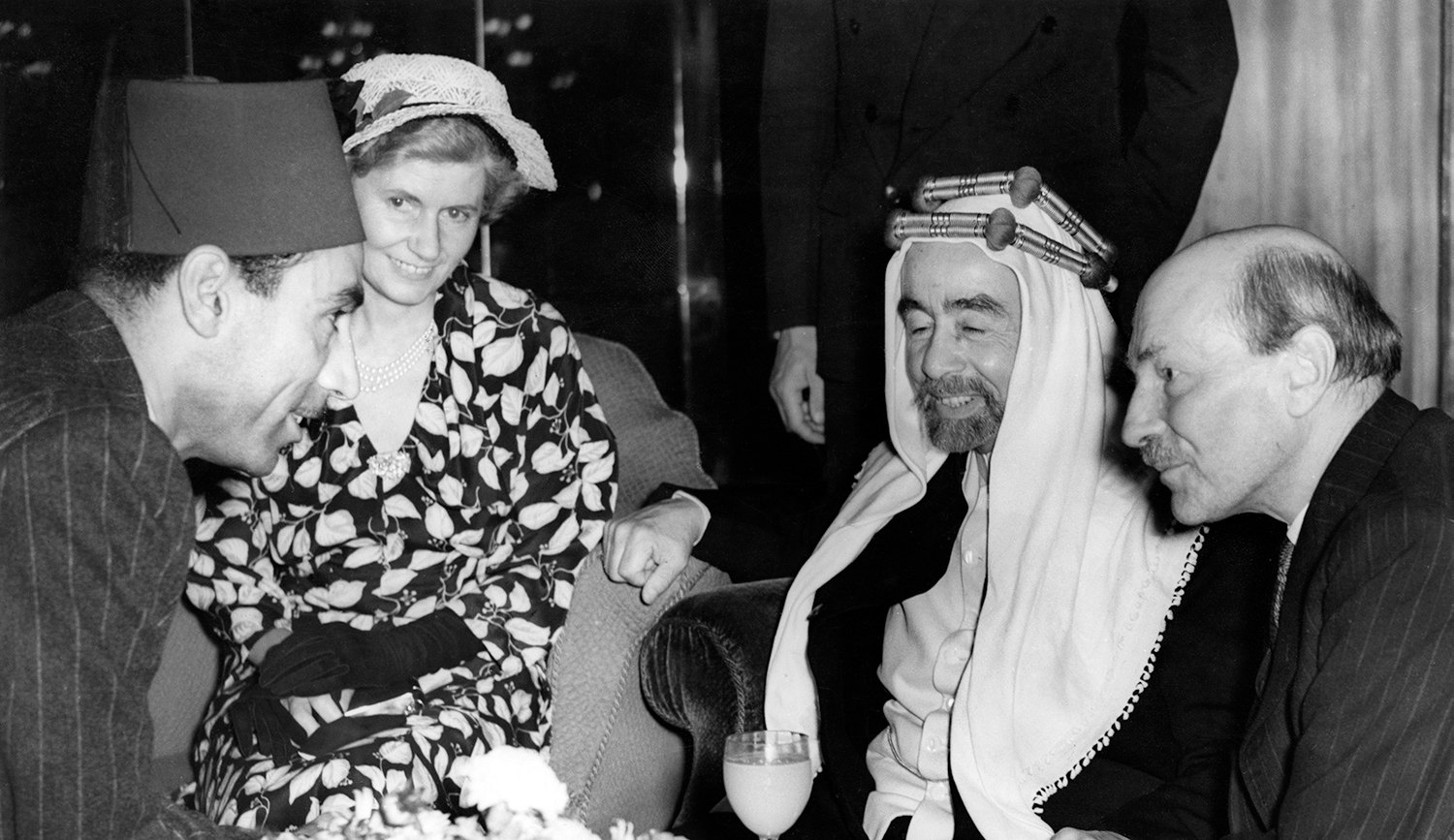

Sixth, Abdullah didn’t need to worry much about how his move would be viewed internationally, because Jordan had no international relations to speak of. The kingdom depended entirely on Britain, which was still hanging on as the principal Western power in the Middle East. Although the United States loomed over the horizon, Abdullah largely left it to the British to finesse the Americans.

To be sure, most Arab states—especially Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia—took a dim view of Abdullah’s ambitions, and even threatened sanctions. But he mollified them by promising not to conclude a formal peace with Israel. In June 1950, Abdullah reassured the Arab League that the annexation was “only an expediency” and that Jordan would rule the West Bank “as a trust pending the final settlement of the Palestine problem.” That neutralized the problem.

Israel’s world is much larger. It has a wide array of open and clandestine diplomatic and political relations across the globe, and it is deeply integrated in the world economy. Yes, the United States is its closest ally, but Europe is its biggest trading partner, Asia is its fastest-expanding market, and more and more Arab countries have become strategic partners as well as buyers.

The bottom line: Israel isn’t indifferent to what the world thinks. Most European governments, Russia, and the Arab Gulf states have warned or advised it against annexation, often in strong terms. Just how much weight should be given to such protestations is open to debate. But they won’t be ignored.

Seventh, not only did Britain recognize the annexation, it did so in a way that obligated the British to defend it. Back in 1946, Britain and Transjordan (as it was then known) had concluded a formal “treaty of alliance.” As revised in 1948, the treaty specified that “in the event of either party being engaged in war or menaced by hostilities, each will invite the other to bring to his territory, or territory controlled by him, all necessary force of arms.”

In May 1948, Abdullah was on his own in sending an invasion force across the Jordan river to fight the birth of Israel. But if he were formally to annex the West Bank, would Britain regard it as territory it was obligated to defend?

Evidently it would. Immediately upon the annexation, Britain announced that it deemed the provisions of the treaty of alliance “as applicable to all the territory in the union.” Although unwilling overtly to recognize Jordanian sovereignty in eastern Jerusalem in particular, it nevertheless considered the treaty to be applicable there “unless or until the United Nations shall have established its effective authority there.” Nor did its guarantee depend at all on whether Jordan finalized its border with Israel.

There could be no more potent form of recognition than its inclusion in a treaty. Thus, to say dismissively that Britain was the “only” country to recognize Abdullah’s annexation is to overlook the fact that Britain was still the foreign power with the largest political and military footprint in the Middle East.

Recall that the Trump administration’s 2019 recognition of the Golan as part of Israel was issued merely as a “presidential proclamation.” What sort of recognition might the United States extend to an Israeli annexation of the West Bank? It wouldn’t be embedded in a treaty, because Israel doesn’t have a treaty with the United States. Nor would it automatically entail any U.S. commitment.

To the contrary, American recognition would be conditional. The Trump administration believes annexation should be part of an agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, or at least be a prelude to such an agreement. According to the administration’s plan, the deal would create a Palestinian state on 70 percent of the territory, with the Palestinians granted four whole years to mull it over.

“All of these discussions relating to mapping and annexation,” said the State Department spokesperson recently, “we firmly believe should be a part of discussions between the Israelis and Palestinians working toward President Trump’s ‘Vision for Peace.’” So far, the administration has not opened a clear path to American recognition outside acceptance of the “vision.”

Abdullah’s eighth advantage was that in Britain, his superpower patron, there was no party division over his planned move. In April 1950, Clement Attlee stood at the head of a Labor government. When the matter of British recognition was presented for information to the House of Commons, the leader of the Conservative opposition, Winston Churchill, welcomed it. (Churchill, colonial secretary when Transjordan was created in 1922, had, as it were, a stake in its well-being.) Abdullah also didn’t have to worry that British recognition might be rescinded by a new prime minister from the opposition party: none other than Churchill replaced Attlee in 1951. Britain’s recognition, said another Conservative MP, was “entirely non-party.”

This could hardly be said of the American view of an Israeli annexation. Last December, a non-binding resolution passed by the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives decried “unilateral annexation of territory” as a step “that would put a peaceful end to the conflict further out of reach.” Joseph Biden, now the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, is on record saying that “annexation would make two states impossible to achieve.” Democrats differ over how forcefully they should stand against annexation, but it has already emerged as a partisan issue.

Abdullah’s ninth advantage was that Britain, even though it still dominated the Middle East in 1950, went out of its way to secure Washington’s tacit approval for Abdullah’s West Bank annexation. The act received a discreet nod of favor from the State Department, although it would have preferred “the union to take place quietly, as a sort of prolongation of a de-facto status quo.” As the State Department later explained to the British,

although we favored the inclusion of central Palestine in Jordan at the appropriate time, we felt that unilateral action to that effect by the Jordan government was of such a character as to make it difficult for us to announce official and public approbation.

Be that as it may, in the week before the final annexation an internal State Department summary of policy toward Jordan informed American missions around the world that “the United States with the United Kingdom has favored the annexation by Jordan of Arab Palestine.” When the U.S. secretary of state Dean Acheson was asked about it, he cited the West Bank elections to Jordan’s parliament, adding that “our American attitude was that normally we had no objection whatever to the union of people who were mutually desirous of this new relationship.”

In other words, the United States wouldn’t explicitly endorse the annexation, but neither would it object. And that was more than enough. After all, as the British cabinet was assured by the Foreign Office, a U.S. statement in favor of the recognition “would not commend our policy to the other Arab states; and, in the eyes of public opinion in other parts of the world, it needed nothing to commend it.”

At this moment, by contrast, no major ally of the United States has shown a willingness to nod its support for American recognition of annexation. Worse, Britain, the traditional partner of the United States in the Middle East, has objected openly to such a move, describing annexation as “contrary to international law.”

Tenth advantage: Israel itself, Abdullah’s immediate neighbor, acquiesced in his move. At the time, Israel would have preferred a small, pliant Palestinian Arab statelet next door, but Abdullah alone held the ground. Some Israeli diplomats even concluded that Jordanian annexation was in Israel’s best interest. Israel’s foreign minister, Moshe Sharett, told the cabinet in February 1950 that the previous year’s armistice agreement already served as a kind of de-facto recognition:

Abdullah has taken many steps that are tantamount to a declaration of sovereignty. We committed ourselves not to attack him decisively, so that it’s possible to read the armistice as confirming recognition of his sovereignty.

Still, after the “unification” in April 1950, the Israeli government registered its reservations:

The decision to annex the Arab areas west of the River Jordan to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a unilateral act which in no way binds Israel. . . . No final settlement is possible without negotiations and a peace treaty between the sides. It must be evident, therefore, that the question of the status of the Arab areas west of the River Jordan remains open as far as we are concerned.

At the same time, however, Israel refrained from campaigning against Jordan’s action. Its tacit acceptance of the new facts was eased by direct assurances that Britain would not put military bases in the West Bank during peacetime. At Israel’s request, Britain announced this publicly and further sweetened the pill by extending to Israel the de-jure recognition it had hitherto withheld.

When opposition members of the Knesset accused the Israeli government of acquiescing in Abdullah’s “act of plunder,” Sharett strongly repudiated the charge, adding, however, that he did “not see why some people have seen fit to treat this matter as if the end of the world were approaching.”

Today, again by contrast, Israel has been warned by its immediate neighbor, the present King Abdullah (great-grandson of the first), that Israeli annexation “would lead to a massive conflict with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.” No one knows what that means for certain—it probably wouldn’t mean “the end of the world”—but it doesn’t have the ring of acquiescence.

Last option standing?

We come now to the eleventh advantage enjoyed by Abdullah that Israel also shares.

By 1950, the two-state solution envisioned by the United Nations in its 1947 partition plan had died, and no one saw a credible way to revive it. While the Zionists had accepted the idea of partition in principle, they had reservations about the map that accompanied the proposed plan. The Arabs rejected both the principle and the map. Even before Abdullah entered Palestine, Jews and Arabs there had descended into months of bloody civil war, and the Arabs, in defeat, had collapsed politically.

In this vacuum, Abdullah’s annexation plan, even among those who disliked it in principle, met little practical resistance. And this is similar to the situation today.

For decades, it’s been a pious mantra that the two-state solution is the only solution to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. But every attempt to produce it has met with dismal failure. Negotiators have convened, mediators have shuttled, pressure has been applied, maps have been sketched, and publics have been polled. Yet the two parties are no closer to this dreamed-of solution.

In such a situation, whatever hasn’t been tried gains by default. If the parties can’t reach an agreement, perhaps unilateral steps might work?

One version of such a step is unilateral “separation” in the form of an Israeli withdrawal. The problem here is that many Israelis believe this has been tried before and failed—not in the West Bank, but in Gaza. Or they believe that the outcome that Israel now tolerates in Gaza can’t be tolerated in the West Bank.

The other step is unilateral annexation. Today in Israel the pros and cons of such an annexation, in its many varieties, are being debated at length and in depth. The driver of the entire process is the unprecedented prospect of American recognition. After all, annexation of a territory you’ve already controlled for more than a half-century is useful only if someone important recognizes it. True, as things now stand, Israeli annexation would be described, at best, as having been recognized “only by America,” echoing the very claim used by Israel against Abdullah: that his annexation was recognized “only by Britain.” But since there may never be a prospect of getting more recognition than that, why not seize the opportunity?

That argument looked stronger back in the winter, before a pandemic, an economic crisis, and racial unrest turned American politics upside-down. Now Joe Biden has become the candidate to beat. “I do not support annexation,” he has told Jewish donors. “I’m going to reverse Trump administration steps which I think significantly undercut the prospects of peace.” If, as a result of November’s U.S. election, a Democratic president rolls back recognition, Israel’s annexation will be remembered as having been “recognized only by Trump.”

In that case, not only will annexation have added no value, Israel will have experienced the humiliation of seeing its sole patron retract the only recognition it will have received.

The haunted annex

The broader history of annexations includes not a few duds. Some ended up changing the world map, others got reversed. It’s hard to know in advance which ones will stand the test of time or will end up as footnotes, because historical forces don’t obey decrees.

Abdullah’s annexation is a case in point. True, he got his West Bank, and along with it the Old City of Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock, and al-Aqsa mosque. Finally, he had a kingdom worthy of the Hashemite name! He thought he would go down in history as someone who had redrawn the expanded borders of a Greater Jordan.

But with the West Bank came the Palestinians, who nursed their grievances against Israel and very soon began to transfer them onto Abdullah himself. Tensions began to rise. In July 1951, he went to Friday prayer at al-Aqsa as king and sovereign. There, a Palestinian Arab assassin and disciple of Haj Amin al-Husseini, acting on behalf of a wider circle of conspirators, shot him dead. Thus did Abdullah pay the ultimate personal price for his acquisition.

Nevertheless, for some years the glue of annexation seemed to hold—until it didn’t. Jordan’s involvement in the West Bank led it into a war with Israel in June 1967 and three years later into a civil war (“Black September”) that almost brought down the Hashemite monarchy. What looked like an opportunity in 1950 turned into a huge risk. It was with a palpable sense of “good riddance” that Abdullah’s grandson, King Hussein, finally dropped any Jordanian claim to the West Bank in 1988. The first Palestinian intifada of the previous year persuaded him that Palestinians wouldn’t again acquiesce in rule from Amman.

The case of Abdullah’s 1950 annexation of “Arab Palestine” shows that a bold leader can play his advantages well, redraw the map, gain some recognition, and still leave only regrets. Today, Abdullah’s ghost stalks the haunted annex between Israel and Jordan. History never repeats itself down to the last detail. But since the Jews are a people who believe that history does teach lessons, they shouldn’t entirely disregard the cautionary tale of the covetous king who got more than he bargained for.

More about: Annexation, Examining Israel’s Eastern Borders: A Symposium, Israel & Zionism, Jordan, West Bank