At the height of the Yom Kippur War, Henry Kissinger—never one to suffer from low self-esteem—told his boss “Mr. President, this has been the best-run crisis since you have been in the White House.” Michael Doran would echo the sentiment, given his claim, in his excellent treatment of the war earlier this month in Mosaic, that Nixon and Kissinger were “the greatest supporters of Israel that have ever run American foreign policy.” Alas, facts are stubborn things, and the Nixon tapes are, at least for historians, the gift that keeps on giving. Thus, as I researched the historical record for my new book Eighteen Days in October: the Yom Kippur War and the Making of the Modern Middle East, I never thought of Nixon and Kissinger as great supporters of Israel. Rather, I was reminded of Winston Churchill’s observation that Americans always do the right thing—but only after exhausting all the other options.

Others before them exhausted the other options faster. At the 1968 Independence Day parade in Jerusalem, the Israelis could only fill the skies by sending up every contraption that could fly. Those in the know understood that the vaunted Israeli Air Force was down to its last 130 fighter jets. With France, Israel’s heretofore supplier, now imposing an arms embargo, Prime Minister Levi Eshkol turned in desperation to Washington. President Lyndon Johnson was advised to hold Eshkol’s feet to the fire and demand, at a minimum, that Jerusalem abandon its nuclear program. He could have demanded far more than that. Any offer was an offer the Jewish state could not refuse.

But Johnson ignored the advice, agreeing to sell tanks as well as fighter jets, and to speed up production so that the Israelis could take delivery in 1969 instead of 1970. With these no-strings-attached sales, Lyndon Johnson did more to guarantee the security and survival of the Jewish state than any American president before or since.

There was reason for optimism in Jerusalem when the hawkish Richard Nixon entered the White House in 1969. Early in his presidency, Nixon established a “doctrine” committing the United States to “furnish military and economic assistance [to allies] when requested.”

The trouble with the Nixon Doctrine was that it was overseen by Nixon. He delighted in telling associates and visitors that he was impervious to pressure from the “Jewish lobby,” often joking that the few Jews who voted for him “had to be so crazy” that they would stick with him even if he turned on Israel. It did not take long for him to do just that.

In February 1970, the French president Georges Pompidou came to the United States on a state visit. Pompidou’s advance men did a poor job scouting out the American landscape, and Israel’s supporters—angered that French fighter jets Israel contracted to purchase were instead sold to Libya—greeted him with protests wherever he went. It was a rebellious age, and in Chicago pro-Israel protesters hurled what Henry Kissinger described as “especially offensive” insults at Pompidou’s wife. (The visit occurred shortly after the Markovic Affair, a sordid tale of sex parties and mobsters in which French police uncovered sexually explicit photos of Madame Pompidou in a murdered man’s car). An enraged Pompidou threatened to cut the visit short, and an equally enraged Nixon retaliated against the protesters by cutting off arms sales to Israel.

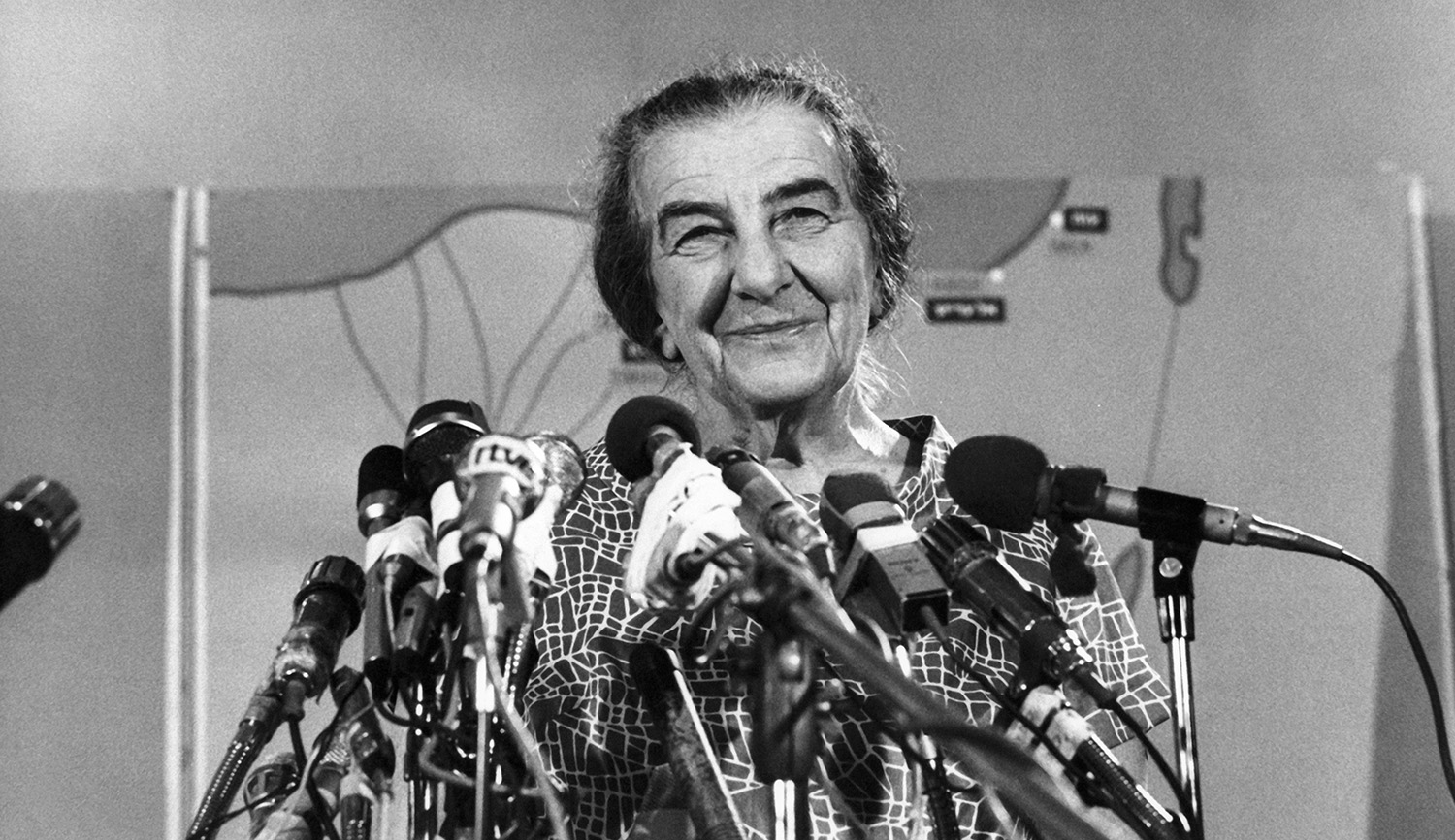

From that moment, Washington became a questionable supplier. Israel’s prime minister was by then Golda Meir, a woman with perfect American-accented English and what Teddy Kollek called “an unequalled gift for turning emotion into cold cash.” On one Washington visit she was asked by reporters if Israel would ever use nuclear weapons, and to gales of laughter she replied that they were doing just fine with conventional weapons. Each time Washington cut off the arms flow, Golda found a way to pry the spigot back open. But each mini-crisis involved caving to American demands regarding management of the War of Attrition, or the peace process.

The threat of an arms cutoff thus always hung heavy in the air. In December 1972, Kissinger told the Israeli ambassador to the United States, Yitzhak Rabin, that “it is critical that Israel not break the ceasefire, even if it has information of an Egyptian intention to restart the war.” Kissinger was no less emphatic on the morning of October 6 when all feared an imminent attack. It is true that Golda might not have given the order to launch a preemptive strike even with a green light from Washington. Weather conditions were unfavorable, the army was still mobilizing, and there was still a chance that the Arabs were only bluffing. Moshe Dayan scoffed that they’d heard warnings of attacks in all the other months, and now it was October’s turn. But it is also true that if such an ultimatum had been issued by the Johnson administration in 1967, the IAF would have spent the opening hours of the Six-Day War defending Jerusalem rather than destroying Arab planes on the ground.

Israel’s willingness to listen to the Americans and absorb the first blow won it few friends in Washington. At a special meeting held on October 6, Defense Secretary James Schlesinger said the only question the group should consider was whether to label the Israelis “aggressors.” Then, on the morning of October 9, Kissinger was informed that Israel had experienced the staggering loss of 500 tanks and 49 planes. “So that’s why the Egyptians are so cocky,” he sighed. But promised weapons were held up, the victim, Kissinger claimed, of a bureaucratic “runaround.”

The record begs to differ. Schlesinger said in an October 26, 1973 press conference that arms shipments were deliberately held up to pressure Israel into accepting an early ceasefire. This statement is backed up by NSC staffer William B. Quandt in his memoir as well. As Kissinger describes it in his own memoir, it was only after Sadat turned down the ceasefire proposal on October 12 that—with all options now exhausted—he called his aide Brent Scowcroft and told him “to pour stuff in there.”

To be sure, Kissinger also engineered a generous $2.2 billion economic aid package for Israel, one that enraged King Faisal of Saudi Arabia and caused him to impose the oil embargo against the United States. Kissinger writes that he authorized it because he never dreamed it would trigger such an angry response from the Arabs. It showed that he was prepared to help Israel when he thought he could do so on the cheap, and that he meant what he said when he told Golda that he saw himself first as an American, second as a secretary of state, and only third as a Jew. (In an oft-repeated joke, she reminded him that Jews read from right to left.) Of course, no one ever criticized Kissinger for placing American interests first. It was rather his defense of those interests that still raises eyebrows.

Which brings us to arguably the biggest blunder of his career. On October 20, Kissinger was summoned by the Soviets for emergency talks. At Sadat’s behest, the Soviets pushed to impose a ceasefire before the Israelis could encircle the beleaguered Egyptian Third Army. Upon landing in Moscow, Kissinger learned of the Arab oil embargo. Nevertheless, he agreed to impose a ceasefire on Israel, just as it was about to win the war, without demanding that Saudi Arabia lift the embargo. This was the moment when Kissinger held all the cards. It is difficult to see how King Faisal could have turned down a demand that the rescue of the Egyptian army also include a rescue for gas-starved American motorists. But Kissinger did nothing to press the issue.

Fortunately for Israel, Golda had other ideas. She ordered the IDF to surround the Egyptian Third Army in defiance of Kissinger, Moscow, and the rest of the international community. Back in Washington, in early November, an outraged Kissinger demanded that Israel release the grip on the Third Army and pull back to the October 22 line. These were the most acrimonious meetings ever between an Israeli prime minister and an American secretary of state. Kissinger threatened that if fighting broke out again, Israel would go it alone without resupply from Washington. Golda dug in the heels of her orthopedic shoes and refused to budge. The standoff continued for an entire week until there was a breakthrough: the Egyptians gave in. The Israelis could remain in place. An agreement would be implemented on Golda’s terms. The Israelis had won the Yom Kippur War.

The separation agreements of 1974 and 1975 deprived the Arabs of any future military option. Egypt and Syria were thus presented with a stark choice: make peace with losing the 1967 lands or make peace with Israel. Syria chose the former. Sadat chose the latter, signing the first Arab-Israeli peace treaty in 1979. Since that time, Kissinger’s supporters have argued that it was his grand strategy that had delivered peace. In truth, if Kissinger had had his way, the peace treaty would never have happened because Israel would have lost the Yom Kippur War.

Kissinger can rightly take credit for the shuttle diplomacy after the war, where his patience and brilliance for detail allowed the parties to achieve what few thought was possible. But it was Golda’s iron determination that set the stage for the outcome. It was her refusal to take no for an answer that closed off all the other options.

More about: Henry Kissinger, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism, Yom Kippur War