The Hamas terror attacks of October 7 took place almost 50 years to the day after the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War. As in 1973, the surprise assault will have far-reaching consequences for the Israeli military, Israeli politics, the U.S.-Israel relationship, and the future of the Middle East. On October 18, Michael Doran—author of “The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War” and teacher of an online course on the same subject—joined Mosaic’s editor Jonathan Silver for a conversation reflecting on the echoes between those two events.

Watch the recording or read the transcript below to learn about:

- How Israel was caught so flat-footed 50 years ago, and what errors allowed Hamas to execute such a deadly massacre this year.

- What Anwar Sadat tried to achieve with Egypt’s surprise attack, and what Hamas is trying to achieve today.

- How Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s conception of the U.S.-Israel relationship affected the outcome of the Yom Kippur War, and what the Biden administration’s policies toward Israel and Iran mean for an extended conflict with Iran’s proxies.

Watch

Read

Jonathan Silver:

Mike, when you and I first started to talk about your work on the Yom Kippur War, I think back in the spring, our purpose was to focus on the 50th anniversary. And at that point, our challenge was to try to recreate the emotions of bewilderment and dread that gripped the Israeli body politic, and to remind people how important intelligence and operational proficiency in military matters really are. Today, we do not need to remind our readers of any of that, unfortunately. It’s all horribly, unspeakably manifest before us in the Hamas massacres of October 7th. I want to come back to the military situation in Israel today at the end of our conversation.

But first I want to begin with the Yom Kippur War of 1973. You’re offering here a novel interpretation of the war. And I think to understand what’s so novel about your interpretation we have to put onto the table some of the more conventional understandings of how the war is remembered. Memories and trauma of the Yom Kippur War have festered in the Israeli consciousness for the last five decades. And undoubtedly they capture something real, but they also, like all memory, capture part of something and not the whole of it. Before we come to your views on the matter, why don’t we start with how the war has been remembered in Israel?

Michael Doran:

Thanks, Jon. Thanks also to Tikvah for doing this. And before I answer the question, let me just give a special thanks to Josh and Mrs. Landes. I really appreciate all the support that they give me at the Hudson Institute, and also for this course. It’s really wonderful to have people like Josh helping us do our work.

I think the conventional popular understanding is that Israel was taken by surprise, and that it was a very bloody war. It’s the second-bloodiest war after the War of Independence. And I think the sense is that it was so bloody because they were taken by surprise. The phrase that the Israelis use to talk about the war is meḥdal, which is a blunder. The word actually means omission leading to great harm—the things that weren’t done that should have been done. If there hadn’t been these omissions, then there wouldn’t have been all of the bloodletting. And I tried to call that into question in some regards. I think there were some factors that haven’t gotten as much attention as they deserve, and I think some of those same factors apply to what’s going on today, and people I don’t think have gotten their heads around that. I hope the essay will help them to think about it a little bit.

Jonathan Silver:

The notes that the war strikes in the Israeli consciousness are notes of inadequacy, lack of preparation. The meḥdal is the omission, but what actually happened? Maybe let’s just start there. What happened in the war?

Michael Doran:

It depends on where you start the story. The Israelis in the week or two before the war started getting lots of reports that a war was in the offing. Very credible reports, including a secret trip by King Hussein of Jordan to Israel to meet with Prime Minister Golda Meir and to tell her that the Egyptians and the Syrians were planning a major assault. And Israeli military intelligence—at the time, there was only one intelligence analysis unit—discounted all of the reports. There were many reports, many signals from many different places that came in.

And they discounted all of it because they had this notion that they called the konseptzia, the conception. They had an intelligence conception which told them that unless Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, had long-range bombers that could counter Israeli air superiority, he wouldn’t go to war. And if Sadat wouldn’t go to war, the Syrians wouldn’t go to war because they couldn’t go on their own. So all the signals from Syria were discounted, because Israel “knew” Sadat wasn’t going to go to war, and all the signals from Egypt were discounted because they knew that Sadat didn’t have the bombers and other weaponry.

Jonathan Silver:

Clearly, one of the problems is now looking back with the benefit of hindsight and seeing the flaws of that conception. But just to give it its due, we should maybe just rehearse the reasons why it wasn’t crazy to think that at the time. If you had just lived through the Six-Day War, then you can sort of figure out how you might reason your way to that conclusion.

Michael Doran:

Exactly. In the Six-Day War, Israel had air superiority that allowed it to carry out a preemptive strike. The preemptive strike completely neutralized the Egyptian air force, and then later the Syrian and Jordanian air forces. And without air power in desert warfare, you can’t protect your forces, so the ground forces were exposed.

The Egyptians and the Syrians were also badly trained. One of the stories that the Israelis tell themselves about the 1973 war, and I don’t think erroneously, is that there was a fair degree of hubris in the system. Because the Israeli forces had been so superior to their Arab rivals, there was a sense that the Arab rivals would never be on the level of the Israelis. I think we’re living through a similar moment. Clearly, in addition to all of the atrocities that Hamas committed on October 7th, it also killed a lot of Israeli soldiers. Over 300 Israeli soldiers died that weekend. And so, it’s something to think about. Not all of those soldiers were caught off guard, some of them were some of Israel’s most elite units.

Jonathan Silver:

So, there’s a question about the ability to decipher intelligence reports that are coming in. There’s a question about the overall conception, the tactical concept of the Israeli military at that moment. What are the other factors that might have led to the war?

Michael Doran:

The worst military blow that the Israelis got came from a very innovative Egyptian war plan. Sadat built a surface-to-air-missile wall along the Suez Canal, and the range of the surface-to-air missiles extended over the canal, several miles into Israeli-controlled Sinai. When Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal into Sinai, they were under the cover of these surface-to-air missiles, thereby neutralizing Israeli air superiority.

The Israelis also failed to imagine that Sadat might launch a war that he couldn’t win. If you assume that, at a minimum, Sadat’s goal was to get back the Sinai, the Israelis understood that there’s no way that he could muster enough force to take back the Sinai. But he didn’t try to do that. He just tried to deal a terrible blow to Israel. He knew how sensitive Israel was to casualties, and by dealing a terrible blow he thought he could shake up the diplomacy, and bring the superpowers in so that they would then pay more attention to Egypt’s demands against Israel. And he succeeded in all of that.

The other thing that he did was that he studied the Israeli war plan and the Israeli order of battle very closely, and devised a plan to neutralize the first and second waves of Israeli armor that came at him. And the key weapon system for this was the Sagger anti-tank guided missile. It’s a wire-guided missile. It didn’t make its debut in the 1973 war, but it was sort of the star of the war, after the surface-to-air missiles. Sadat understood that once he surprised the Israelis, the next thing they were going to do was come at him with all they had in terms of their armor, which they did. The Israelis came barreling at his troops. But he was ready. He had men, teams, sitting in place. And that’s why October 8th was the worst day in the history of the IDF: because the Israelis had no idea how powerful these anti-tank missiles were and how they were just going to burn right through the Israelis’ Patton tanks.

Jonathan Silver:

I’ll just note that the surface-to-air missiles and the Saggers are all Soviet supplied.

Michael Doran:

Yes, Soviet supplied.

Jonathan Silver:

So, this is one of the things that will attract a great deal of attention in Washington. And there is a level to your analysis which sees the Yom Kippur War as a proxy war that is one of the signal flashpoints in the cold war. That’s another dimension to it. But now just say a word about the northern front.

Michael Doran:

In the northern front, the Syrians pushed back the Israelis in the first wave, a similar surprise, but also with overwhelming force. But the Syrians were incapable of building a surface-to-air missile wall like Sadat did. So the Israeli air force was more effective in the north than it was in the first days of the war in the south. And the Syrian tank commanders were not as well-trained. I didn’t go into it much either in the lectures or in the essay, but there were acts of great heroism by the Israelis on the Syrian front. It saved the country, really, because a small number of very dedicated men were able to turn back the Syrian attackers, who were actually in position to go down from the Golan Heights into Israel, into the civilian areas. If they had been better trained and pushed their advantage further, they could have broken into Israel proper.

But because of their own relatively poor training—the Syrian tank commanders were better in ’73 than they were in ’67, but they were not as good as the Egyptian ones, and they were definitely not as good as the Israelis—and because of the heroic defenders on the Israeli side, they were turned back. Plus, the Israelis were a little better prepared for the attack in the north than they were in the south, because there had been some tension on the border the month before and the Israelis had never completely stood down their forces like they had in the south. On Yom Kippur in Sinai, there were just 400 some-odd men in position in Sinai, most of whom were reservists who were poorly trained. You had some very well-trained troops, not as many as you needed, but you had some very well-trained troops who were ready in the Golan.

Jonathan Silver:

Here’s another dimension that Israelis remember with regret, with disappointment, with frustration. I think the rapid success of the Six-Day War led Israeli military planners to believe that they would only need the materiel to prosecute a war that would last five days, a week. And because of those early waves of casualties and material losses, they came to the understanding that they were going to need to be resupplied in a hurry. Maybe we can fold in the American dimension now.

Michael Doran:

Already on day two, Golda Meir realized that resupply was going to be a big deal. By day three, absolutely. The commanders could look forward and see that this war was eating up material like no war they had ever fought before, and that it was going to take longer. It was going to be a war at least of weeks. Looking at that and looking at their inventories, they started to get very worried about resupply. The Soviets were resupplying the Egyptians and the Syrians without any problem, but there were some difficulties [for Israel] on the American side.

When you first asked me if I wanted to write about the Yom Kippur War, and do the lecture series, I thought I would just be recycling things that I had learned years ago for people who were not familiar with it. I didn’t expect to be learning anything new. But in doing the research for this, I learned a lot of new things about the war that I did not know.

And one of them was the importance of the War of Attrition, which is kind of forgotten—certainly among Israelis it’s forgotten. Because you have the drama of the ’67 war and the trauma of the ’73 war, the War of Attrition in between just gets lost. When I used to teach at university, I would teach for a week on the ’67 war and a week on the ’73 war, and I would just wave at the War of Attrition as we went by. I realize now that it is absolutely crucial for understanding the ’73 war. The 1973 war is an outgrowth not just of the ’67 war, but also of the War of Attrition.

Jonathan Silver:

In our conversation so far, we’ve made reference to the Six-Day War in 1967, some half-dozen times already. But maybe it’s worth unpacking what the War of Attrition was.

Michael Doran:

The War of Attrition was a Soviet-Israeli and Egyptian-Israeli war fought mainly around the Suez Canal. There are commando raids across the canal, dog fights over the canal, and artillery barrages back and forth.

Jonathan Silver:

And this is in the early 70s?

Michael Doran:

From March 1969 to August 1970. Gamal Abdel Nasser, the leader of Egypt, lost the war in ’67. He’s now trying to make sure that the Bar Lev line—that’s the defensive line that the Israelis built along the Suez Canal—does not become a permanent political boundary. He’s trying to bring enough pressure to bear on the Israelis and on the international community to force them to give up territory, and the Soviet Union comes in behind him. The Soviet Union, of course, was deeply embarrassed by the ’67 war, so it heavily supports Nasser. When he begins the War of Attrition, the Israelis respond. They try to get some leverage over him by carrying out deep-penetration bombing far west of the canal in the environs of Cairo. but Nassar doesn’t behave the way they had hoped. Instead of pursuing for a ceasefire, Nassar goes to Moscow and says, you’ve got to help me. So the Soviet Union doesn’t simply send weaponry. It sends forces; it sends pilots and surface-to-air missiles and the teams to man them. So you’ve got Soviet fighter pilots and Soviet trainers on the ground, and also Soviet troops who are monitoring the air-defense systems.

This is when a lot of the attitudes around the ’73 war on all sides—on the Egyptian side, on the American side, and on the Israeli side—are formed. This is the Nixon administration now. There’s a fear in Washington that this is going to escalate into a Soviet-American conflict, and that’s also the fear that hovers over the ’73 war. You have the Soviet Union and the United States jockeying for position opposite each other, trying to get one over each other, at the same time fearing that this thing could turn into an actual hot war between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Jonathan Silver:

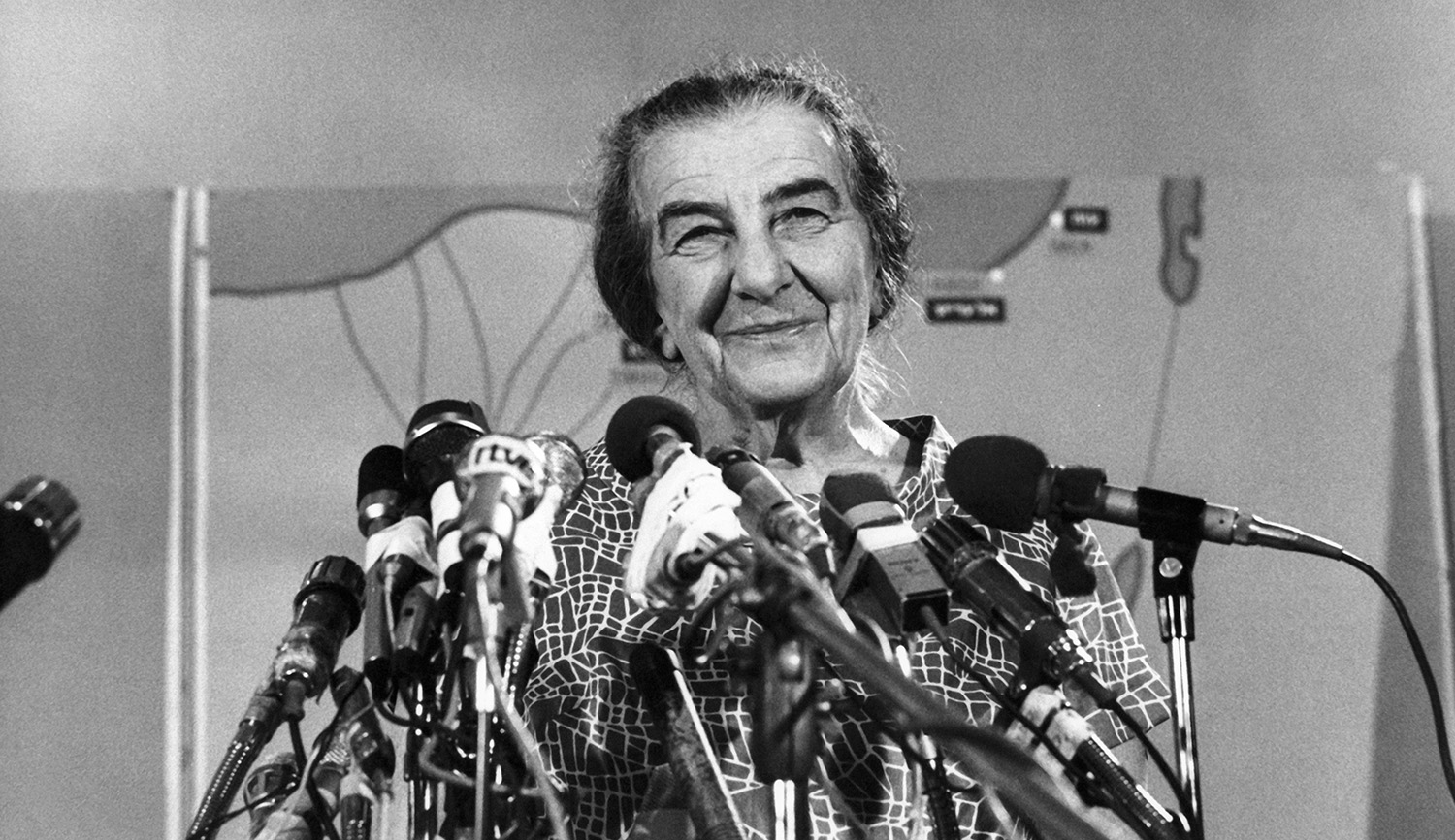

This is crucial background to understanding the psychological dispositions of the key figures of the Yom Kippur War: Golda Meir, Moshe Dayan, and David “Dado” Elazar.

Michael Doran:

We were talking about the issue of resupply. Coming out of the War of Attrition, there’s a deal. This is the biggest thing that I discovered that was completely new to me. I hadn’t understood this previously. There’s basically a quid pro quo that comes out of the War of Attrition, which is that the United States agrees to guarantee Israel what we now call the QME, the qualitative military edge. The U.S. will make sure that Israel has the weaponry it needs to be superior to any conceivable coalition arrayed against it, so long as it doesn’t try to preempt its enemies.

The Americans don’t want the Israelis to start a war. This is a quid pro quo that they enter into with the Israelis in order to get the Israelis to accept the ceasefire in the War of Attrition, because they’re not inclined to accept the ceasefire—they want to win the war.

Jonathan Silver:

They want to press their military advantage.

Michael Doran:

They want to press their advantage, and they’re afraid that a stalemate will be seen as a defeat. We’ve got to think about all this with regard to today as well. All of it. Everything I’m saying, including the resupply question. The kind of deal that was struck between Richard Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger on the one hand, and Golda Meir on the other, is: we’ve got your back; we will resupply you, provided you don’t preempt.

Jonathan Silver:

No more ’67-style air raids and attacks. You can’t do that anymore. But on the other hand, the American superpower will back you.

Michael Doran:

Right.

Jonathan Silver:

So now, since so many of the dominant personalities of the Yom Kippur War formed their outlooks according to those constraints and opportunities, let’s just review some of the key people here on the Egyptian side, the Israeli side, and the American side.

Michael Doran:

The key figure on the Egyptian side is Anwar Sadat, who is an amazing figure. He turns out to be one of the most talented practitioners of international politics of the 20th century, I think. I don’t think that’s an exaggeration. He had a remarkable ability to mold the international system or to move it in such a way that allowed him to achieve his goals. He had a remarkable sense of the relationship between politics and military action. It was inscrutable to everyone, including Henry Kissinger, who was also one of the most talented figures of the 20th century.

It was very hard to get anything over Dr. Kissinger, but Anwar Sadat got something over Henry Kissinger. Richard Nixon also, in my view, was an extraordinarily talented practitioner of international politics. He and Kissinger are a remarkable duo. They’re the odd couple of American foreign policy.

I mean, you can’t imagine a stranger pair, but they have the same view of the world, which is what makes them remarkable. Nixon hired Kissinger without really knowing him because of that shared worldview. And then on the Israeli side, we have Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan—probably the figures people are most familiar with.

You also mentioned Dado Elazar, the IDF chief of staff, a tragic figure. He was shouldered with, or saddled with, the responsibility for the intelligence failure at the beginning of the war, I believe, very unfairly. I think he did a remarkable service to Israel during the war. And some of the people who should have been held responsible for what happened—Moshe Dayan, I think, number one—skated. Dayan was not held to account for his mistakes. Elazar cleaned up the mess to a large extent.

My sense is, reading the literature, that there’s a growing feeling in Israel as well that Elazar got the short end of the stick. And I hope that that will be corrected for his sake, and also for his children.

When I was writing the essay, I always thought I was going to make the case in defense of Elazar, but I never did, because there was always so much else to talk about. But there are others who will make it better than me anyway.

Jonathan Silver:

So let’s just round out the story. The Israelis grow extremely concerned about resupply and have in the back of their heads the deal that was struck in the aftermath of the War of Attrition. Bring us through the end of the war so we can see how it played out, and then we’ll come back to some themes that emerge.

Michael Doran:

The war starts on Saturday October 6, and then just over a week later, on October 14, the United States starts a massive airlift. In between, there’s some dragging of the feet. It’s controversial to this day exactly why the Americans did not rush to resupply Israel immediately. I don’t think we necessarily need to get into that. If you want to, we can. But it is of course one of the issues that is held against Kissinger. There’s a claim out there that Kissinger wanted to make Israel bleed in order to have it softened up for the diplomacy afterwards. I don’t actually believe that, but a lot of people have made this case in a lot of different ways.

Around the same day the resupply comes in, the Israelis go on the offensive—partially because the resupply has arrived and made them more confident in their abilities, and also simply because of the battlefield dynamics. After the offensive begins, the whole tide of the war then begins to change. By the time the 14th comes along, Israeli troops are already barreling toward Damascus. Meanwhile, in the south they begin the process of surrounding the Egyptian Third Army, which has crossed the canal and taken control of the southwestern tip of the Sinai. The Israelis then cross over the Suez into Egypt. Ariel Sharon crosses the canal very dramatically and comes in behind the Egyptians. He’s poised to destroy the Egyptian Third Army, and then the superpowers—the U.S. and the Soviet Union—shut down the war, as Sadat intended from the beginning.

Israel could tell itself, if it wanted to, a story of victory on the battlefield, because the IDF was poised to destroy the Egyptians. But the war ended in a kind of a political stalemate. A political stalemate and an Israeli military victory that came at such a high cost—because those first days of the war were such a shock and were so bloody.

Jonathan Silver:

So you could say that, in a certain sense, if you were to ask an Egyptian who’s thinking about the war as Sadat thought about the war, that Egypt achieved its objectives.

Michael Doran:

Yes.

Jonathan Silver:

It had a very impressive military beginning to the war and a very impressive political ending to the war. Whereas just as likely, if you were to ask an Israeli, an Israeli could say, despite the fact that we did not start the war well, we actually had an impressive military ending to the war—the IDF on the road to Damascus, the Egyptian Third Army encircled, etc. And then there were constraints, political constraints brought upon by the U.S., but we can see it as a victory too.

Michael Doran:

Right. And there are scholars out there, Israeli scholars, who strongly resent the standard narrative and are frustrated that the war is remembered popularly in Israel as a big blunder. And there’s no way to get away from this. I think I talked about it in the essay, that it’s not just remembered in Israel as a blunder, it’s remembered as the blunder. Now we’re going to have the blunder of 2023 that’s going to rival it in the popular history; it will be interesting to see how that’s incorporated into the story. But it’s so deeply ingrained in the Israeli collective memory that you can refer to a “Yom Kippur of something” as its worst moment.

You could say your class on the Yom Kippur War with Doran was the Yom Kippur of the Tikvah Fund. (I hope that’s not true.) But that’s how you would use it if you wanted to say such a blasphemous thing. I know you would never say such a thing.

There are scholars out there who reject this narrative and are working hard to say, “No, this was a great military victory. Why do we put ourselves down in this way?”

Jonathan Silver:

But it’s as if scholars, by way of analogy, came to the American body politic and said, “Actually, you achieved all these objectives in the Vietnam War.”

Michael Doran:

Yes. There are those who do make that claim about Vietnam, by the way.

Jonathan Silver:

But nevertheless, it is firmly encoded in the American psyche that that was a trauma and a loss. And similarly in the Israeli psyche, the Yom Kippur War is a trauma and a loss.

Michael Doran:

That’s a great analogy. But it’s also part of a pattern in Middle Eastern wars. If we go back to 1956, Israel routed the Egyptians on the battlefield but Egypt won politically—not just against Israel, but against Britain, France, and Israel. If people are not familiar with the story, we don’t need to tell them. But you can say in ’56, it is an open question who won and who lost, and you can make an argument—one that’s completely coherent and I think valid—that both Israel and Egypt won the war in ’56.

Egypt’s goals were to get rid of the British and the French. That was its number-one goal, and it wanted to push Israel back out of the Sinai after the war was over. The Egyptians got all of that. But they totally lost on the battlefield. So the Israelis can say that they won, because they won on the battlefield. Because of the superpowers, the powers that are actually arrayed against each other on the battlefield are never the ones who determine the peace afterwards. It’s those outside powers that are the dominant powers. They are always there at the negotiating table afterwards to decide whether you get to keep the piece of territory that you took with your military or not. And that adds a whole level of complexity to all things.

Jonathan Silver:

There are many more directions that we could go in. I want to turn soon to contemporary affairs and then invite questions from our audience. But let me just ask one other big thing about the history. The drama of your essay in Mosaic is structured by the question of why Israel didn’t preempt.

Michael Doran:

Right.

Jonathan Silver:

So what’s the answer to that question?

Michael Doran:

The Americans wouldn’t let them. A lot of Israelis know this, but it doesn’t get much attention. Not just Israelis—a lot of people know that Israel was restrained in ’73—but it doesn’t get as much attention as it deserves. It’s part of the story that’s overshadowed by this whole question of the intelligence failures. Imagine if President Biden, when he met with Prime Minister Netanyahu, quietly gave him some advice about what to do and what not to do. For example, “Don’t you dare start a war with Hizballah in Lebanon,” which I believe he did say. (I’m saying this based on my reading of the body language of everyone and their statements in public. I’m not privy to any private or secret information.)

Jonathan Silver:

We should say that there’s unconfirmed reporting to that effect.

Michael Doran:

Unconfirmed reporting to that effect. But I believe that’s what President Biden did, although I admit to not having any solid evidence. Let’s just say, for the sake of discussion, that’s what Biden did. Israel is so happy with the indispensable support that it’s getting from the Americans—even if Israel’s not happy with being restrained in Lebanon—that it would be very unwise to insult the Americans or to say publicly to the Tikvah audience that we’re being constrained. Israeli politicians and generals can’t go around saying, “We can’t go after Hizballah, our primary enemy, because the Americans won’t let us.”

Something like that is at work in the lead up to 1973 war and afterwards as well. Israel would be a bad ally if it complains about the restraint. But the restraint is absolutely crucial for understanding every decision that’s made.

Jonathan Silver:

There’s an additional dimension that I learned from your course and your essay that I want to put on the table here too. The intelligence was faulty. The Israelis did not know the precise hour that the attack was going to come, and so on. But your argument puts forward the proposition that, even if the Israelis did know the exact hour, and even if the Israelis were to preempt, they did not know the effectiveness of the new technology. They did not know the intensity of the arms arrayed against them. They were not prepared for the onrush that was coming to them, and it wouldn’t have mattered.

Michael Doran:

Exactly. The Israelis, first of all, did have advanced warning. There’s this huge discussion in Israel, whenever the Yom Kippur War comes up, about why they didn’t have advanced warning. They had total penetration of the Egyptian military system, just like they have today total penetration of Hamas, and they still got fooled. They were shocked that they had total penetration and yet were still taken by surprise. But even though they were surprised, they still had half a day of early warning, and they decided not to preempt. Then there’s this issue of the very innovative way that Sadat put his surface-to-air missiles and Sagger missiles together, and the war plan that he came up with. Even if they had preempted, they would’ve come up against, in the south, this surface-to-air missile wall, and it would’ve chewed up Israeli planes like it did in the actual war.

Jonathan Silver:

We’ve not discussed the American angle of vision on this war. We’ve not discussed Nixon and Kissinger’s strategic aims. We’ve not really talked about that cold-war context of it. But before we turn to questions from the audience, I want to invite you to dilate on the present situation for just a moment. Everybody was shocked reading the accounts and seeing those awful clips on Twitter and the photos and the heinous barbarity of what happened in southern Israel on October 7th. But seeing October 7th through the lens of October 6th, 1973 allows you to see different things. You could see a different sort of historical and strategic context. Help us understand how the Yom Kippur War can help us make sense of the war that is now in its opening phases.

Michael Doran:

I think there are three things that the war of 1973 can help us understand about 2023. Number one is the “concept of operations.” That’s the phrase, in military jargon, for Sadat’s ingenious combination of tactics, weaponry, and so forth. The concept of operations is how a military commander takes the assets that he has at his disposal and combines them to overcome a challenge or to achieve a goal. The Israelis were not surprised by the existence of the Sagger missile. They were not surprised by the existence of the Egyptians’ surface-to-air missiles. They were surprised at the way Sadat put them together in order to foil the Israelis’ capabilities.

The biggest intelligence failure in the 1973 war was not the failure to see the war coming; it was not the failure of the early-warning system, which has gotten the most attention. It was the failure to imagine the concept of operations. That’s the same thing that has just happened. The Israelis had this high-tech border that they had created, and they didn’t imagine that relatively low-tech weapon systems could be combined in such a way that would completely foil their high-tech. They’re living in a Star Wars world and the world is actually Mad Max. And they didn’t understand that Mad Max can defeat the Death Star.

Jonathan Silver:

I would presume that that’s true not only in military operations, but in intelligence as well. Signals intelligence—intercepting communications and hacking and so forth—can teach you a lot, and surveillance can be really valuable, but it is simply not the same as having human intelligence collection that, though it’s very low-tech, requires a quality of character and courage and savvy, all of which are essential.

Michael Doran:

When I worked in the Defense Department, there was a guy there I knew who came out of the black-ops world, and he spent a lot of time in a lot of holes around the world. He told me that one of the things that he didn’t like about the way America made war is that, in his words, “We will spend 9 or 10 million dollars taking out a radar installation when, actually, if you just walked up to the guy guarding it and offered him a pack of cigarettes, you could just go in and disable it.”

We, the United States—this is not true of the Israelis—are actually very bad at human intelligence. The CIA is our human-intelligence agency, and the CIA has an enormous, enormous amount of information at its fingertips. But that’s because we’re an empire. And so every other human-intelligence agency out there, including the Israelis, feeds its information to the CIA. But if the CIA, on the basis of its own agents who are out engaged in skullduggery in the world, had to tell U.S. what was going on, I don’t think they’d do a very good job. Because we much prefer, in so many ways, signals intelligence. When you’re in government and you see the CIA reports, they’re backed up by signals intelligence. And our adversaries understand this about U.S. They understand that our great strength is listening to their telephones, so they lie on the telephone, or they don’t talk on the phone.

Jonathan Silver:

Meanwhile, plans are hatched and executed through couriers and other very low-tech stratagems.

Michael Doran:

And it works.

Jonathan Silver:

So the first thing is that there was a failure to imagine. What’s the next thing? You said there were three.

Michael Doran:

Second is the American role, which I already alluded to. Right now, everyone is delighted with President Biden. And I don’t want to say that they shouldn’t be happy with a lot that he’s doing, but there’s a bear hug going on with the Israelis, an embrace that can be depicted to the world as an embrace of love, but which is very constraining to the beloved. We need to watch that very carefully. The Israelis are not taking a single step without thinking about the U.S. for two reasons.

One is political. Israel is alone in the world. It’s not totally alone; the Europeans were genuinely shocked by October 7th. But you can see the sympathy for Israel dropping day by day as the war goes on, so there’s a genuine appreciation of the American role here, and there’s a recognition that, without it, Israel at the UN, and politically in general in the world, is going to be in very difficult circumstances.

Then there’s the question of resupply, which is crucial. This is a war that’s going to eat up a lot of material in Gaza anyway. But if it’s a war with Hizballah in Lebanon, this is going to be the worst war Israel has fought in terms of casualties. It already might be the worst war on the home front, I think, though maybe not as bad as the 1948 war. But certainly since the ’48 war you haven’t had civilians killed in the numbers that were killed on October 7. But if Israel goes to war in Lebanon, Hizballah has some 200,00 rockets and missiles, many of which are precision guided. They’re going to use those against population centers. A lot of Israeli civilians are going to die; a lot of Israeli soldiers. Israeli soldiers are already dying in the north.

Jonathan Silver:

I mean, just to stipulate, it relates back to your first point as well: because Israelis are living in a Star Wars world, they have come to believe that—and by the way, I don’t have a single word to say against Iron Dome or David’s Sling, they’re amazing, they’re miraculous—Israelis have come to believe that those things can protect them 100 percent of the time.

Michael Doran:

And they can’t.

Jonathan Silver:

And if a northern front were to open with Hizballah, those systems would simply be overwhelmed.

Michael Doran:

Look at what Hamas did to an Israeli tank with a quadcopter drone and an RPG. A quadcopter that is almost commercially available. These are not really high-tech innovations. It’s a concept of operations, not the technology itself, that allowed for Hamas’s initial success.

And that brings me to the third thing. Iran. Iran, Iran, Iran, Iran, and Iran. And, oh, by the way, Iran. The Iranian role here is absolutely crucial. This is not an Israel-Hamas war. This is not an Israel-Hizballah war. This is an Israel-Iran war. It’s actually an Iran-U.S. war. Thats what’s really going on. And this is not an interpretation. This is objective fact.

First of all, the concept of operations, the money, the technology—everything about this operation has Iran’s fingerprints all over it. The minute the war breaks out, Hizballah starts heating up things in the north. Iran is using its proxies, bringing them together to work in tandem to put pressure on Israel. Today, Iran used its proxies in Iraq to attack two American military bases. And Iran is threatening to intervene directly itself, not simply through Hizballah, if the Israelis persist in Gaza. Iran is there; Hizballah is there; Hamas is there. They’re all on the battlefield in one way or another. The analogy—an imperfect analogy—if we go back to the ’73 war, is that you had the United States opposite the Soviet Union and Egypt and Israel on the battlefield.

Today, it’s the United States opposite Iran. And the attitude of the Americans toward Iran today is much less confrontational than the attitude of Nixon and Kissinger toward the Soviet Union. Nixon and Kissinger were worried about the thing spiraling into a war between the United States and the Soviet Union, two nuclear-armed powers, that could become catastrophic. They were worried about a World War III-type scenario. Today, the United States is trying to appease Iran. It’s appeasing Iran with one hand while trying to help Israel defend against it with the other hand. And there’s a huge contradiction in American policy here, which the Israelis are either unaware of or unable to discuss. Because if they discuss the huge contradiction in American policy, it will get in the way of the support that they’re getting.

Jonathan Silver:

That is the practical effect of the bear hug: it quiets Israel from trying to discuss this tension in American foreign policy.

Michael Doran:

Yes. America is not making policy toward Hizballah, Hamas, and Israel without considering what’s going on in its relations with Tehran.

Jonathan Silver:

We don’t have much time left, but I want to read a few questions from our audience. After Israel defeats and presumably topples Hamas in Gaza, to what degree should Israel and the international community help rebuild Gaza, Marshall Plan style, and try to create a different relationship with the Strip?

Michael Doran:

I don’t want to demoralize everyone, but I’m not convinced they’re going to topple Hamas and occupy the Strip. I know that there’s an overwhelming sense in Israel that this is what needs to happen, and I know that the soldiers are ready to do it, but I don’t think President Biden told Prime Minister Netanyahu that that’s what he wants to see. You don’t have to do a lot of hard analytical work to come to that conclusion, because Biden has said it openly, publicly.

I don’t like a lot of the discussions that are going on these days about the political steps that we’re going to take after Hamas is toppled. I want to see Hamas toppled, and I think what we ought to all be saying is, instead of starting all these discussions about the complex politics that we’re going to find ourselves dealing with after the victory, let’s get the victory in our pocket first.

Jonathan Silver:

As you said before, the U.S. prevented Israel from preemption by conditioning aid. Isn’t it a real strategic problem for Israel that it still seems to need U.S. support for major military operations, allowing the Americans to restrain its freedom of action? That’s what we’ve been talking about.

Michael Doran:

Yes, absolutely.

I also to make clear that the essay and the course are very complimentary to Henry Kissinger and President Nixon. I’m especially drawn to Kissinger. Nixon deserves praise, but I’m especially drawn to Kissinger, because he articulated his policy so clearly for posterity in his memos, and also in his memoirs.

Kissinger saw Israel as an asset to the United States. He’s the first secretary of state to see that. Previous secretaries of state were supportive of Israel and thought that the United States had a special relationship with Israel, that it had a special place in our heart, all of these things. But they didn’t see it as a geostrategic asset, and they didn’t explain analytically and prescriptively how it should be used as an asset. Kissinger did all of that. That’s hard intellectual work that he did, and that’s how we came up with QME and all of these other things. It wasn’t simply him restraining Israel. There was an empowerment of Israel and a use of it as an asset in the cold war that we’re not seeing today.

Jonathan Silver:

So, do 1973 and 2023 expose a lack of strategic thinking by Israeli leaders?

Michael Doran:

I don’t know if it’s a lack of strategic thinking. I think they had the wrong strategy. The thing that has bothered me the most about Israeli thinking for the last decade is that they have not seen how the United States was whittling them down with respect to Iran. They have not seen it clearly, because the debate has focused on the nuclear program and the rising nuclear threat. The Israelis have not understood the shifts in Washington’s Iraq policy, its Syria policy, its Gulf policy, its Lebanon policy.

I saw the United States basically force Israel to make unwarranted concessions to Hizballah in order to get the maritime border. Remember the maritime border? You can see me getting emotional about it. Do you remember how it was supposed to turn Hizballah and Israel into virtual partners? People were saying that it was putting Lebanon on the path to joining the Abraham Accords.

Jonathan Silver:

This was almost exactly a year ago.

Michael Doran:

I remember seeing ridiculous, ridiculous headlines in the Israeli press about how the head of Hizballah, Hassan Nasrallah, had said the word “Israel.” This was hailed as a huge victory. In reality, it was the United States cutting a deal with Iran over the head of Israel. And because the Israelis were myopically focused on their internal fights, they didn’t understand what the Americans were doing to them. The Americans were doing to them exactly what they had done to the Emiratis and the Saudis, exactly what they had done to their Iraqi allies, exactly what they had done to the Turks.

Jonathan Silver:

To defend the Israelis for a minute: Israelis have also taken all kinds of action independently in response to the Iran threat, including all of the work that led to the Abraham Accords and potentially a deal with other partners in the Gulf, as well as independent intelligence operations against Iran.

Michael Doran:

Yes, they’re in a difficult situation. But they have not understood the magnitude of the threat that the U.S. accommodation of Iran is to the region. Forget about the nuclear thing. The nuclear deal was never what it said it was. The stated goal of the nuclear deal was to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon. If you look at its actual terms, as of today, the deal lifted the ballistic-missile restrictions on Iran. Iran can now sell ballistic missiles to Hamas legally, according to international law.

If you look at the terms of the deal, it did not prevent an Iranian nuclear weapon. It’s absurd for any intelligent person to look at the terms of that deal and say that it prevents Iran from getting a nuclear weapon. All it does is take the nuclear dispute and put it off to one side for about a decade. That’s the best it could possibly do. At the same time, it empowers Iran all around the region. And that was the point.

Jonathan Silver:

To create a balance between Iran and on the one hand, and the Gulf states and Israel on the other, to allow America to retreat.

Michael Doran:

The United States, under the Biden and Obama administrations, had a theory which they continue to have today. Perhaps you saw the interview National Security Adviosr Jake Sullivan did a couple of weeks ago with Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic, where he said—and he believed every word—that “the Middle East has been quieter under our watch than at any time in the last seventeen years,” or something like that, “because we are deescalating, because we are integrating the region, because we are engaging in dialogue and diplomacy,” etc.

All of those are words are euphemisms for appeasing Iran, but not just on the nuclear front. Iran’s conventional military capabilities have increased exponentially in the last decade. And so has its concept of operations. They put ballistic missiles, attack drones, and cruise missiles together. They combined them in innovative ways so that they can overwhelm any defensive system that exists in the Middle East, including David’s Sling, including Iron Dome, including the top-of-the-line American systems. For a relatively cheap price, they can overcome any defensive system. And that’s what just happened to Israel with Hamas; it’s what’s going to happen with Hizballah as well.

This is basic military science: you cannot counter an offense-dominant military system—one that favors the attacker, which the systems and techniques that the Iranians have developed do—with purely defensive measures. The United States has been attacked now today, two more times.

Lloyd Austin, the secretary of defense, testified before Congress that U.S. forces in the Middle East had been attacked by Iran or its proxies 84 times since the Biden administration came to power. We responded either two or four times. Let’s say four. Let’s give them the benefit of doubt and say it was five times. That’s 84 versus five. That is ceding the offense to the Iranians. It’s no wonder that Tehran is making these pushes all around the region.

Jonathan Silver:

I want to ask just two more questions. “You make a case,” this questioner asks, “for Sadat as a rational strategic thinker—”

Michael Doran:

No doubt about it.

Jonathan Silver:

—is Hamas rational?”

Michael Doran:

Yes.

Jonathan Silver:

Do they have a goal? And how is understanding that goal going to change Israel’s strategy to counter it?

Michael Doran:

I never understand this question about whether these actors are rational or not. Of course, they’re rational. But they have goals that we regard as crazy. Hamas is happy to lose half the population of Gaza. It will sacrifice that. The slogan of Assad’s forces as they obliterated their own cities was, “Assad or we’ll burn the country down.” That is, either Assad will remain in power or we’ll destroy all of Syria. That was the slogan they wrote all over. This is a mentality that we have difficulty grasping because we assume that they have the same attitude toward their own civilian population and the same kinds of general goals, that they want a better life for their kids, they want a better economy.

They understand us. That’s one of the great strategic deceptions that Hamas carried out over the last two years. They understood how we think, and they convinced us—meaning both the Americans and the Israelis, and the Qataris as well—that they didn’t want to carry out mass-casualty attacks, that they didn’t want to have war; they wanted to have a quiet life and build the economy of Gaza. And we thought, “Ah, they finally get it. They should be building and we’re their partner to help them in this endeavor.” They knew exactly how we were thinking, and they played to it in a very rational way. You can’t be that good at tricking U.S. with our assumptions of the world if you’re not a rational person.

What do they want in the end? They are Islamic extremists. They want to turn the entire world into Muslims, they want to create a new caliphate, and believe that the battle with Israel is the starting point and the catalyst for doing all of that. They have no illusions whatsoever about how powerful Israel is. But they feel that if they keep chipping away, chipping away, chipping away, time is on their side. And if you look at what’s happened in the last few years, there’s a lot to give them optimism.

If I told you in 2008 when we had, I don’t know, 200,000 American soldiers in Iraq that within fourteen or fifteen years Iran was going to be extremely close to taking over Iraq, you’d have told me I was crazy. Iran was weak. Iran is still objectively weak in lots of ways, and yet Iran is a rising military power all around the region. Iran is rivaling the United States in Iraq today. We’re not capable of countering them.

If you’re sitting in Tehran, you can imagine that, within a decade, you may be the dominant power in the Persian Gulf and have all of those vast oil resources. They won’t be totally under your control, but you’ll have Saudi Arabia and the Emirates so intimidated that they will be much more deferential to you and everything that you’re demanding in terms of political and military posture, and also in terms of economic policy. You can imagine them having de-facto control over Iraqi resources. And if you’re sitting in Gaza looking at that, you’d think, “Wow, our star is on the rise.”

Jonathan Silver:

Mike, you and I both share a lot of love for Israel. We’re broken at this moment looking at what’s happened there. What does Israeli military victory look like?

Michael Doran:

Israel needs to destroy Hamas at a minimum. It really needs to destroy Hizballah. At least Hizballah needs to be seen to be suing for peace. I don’t think that’s going to happen. But at a minimum, Hamas has to be brought to its knees. Israel has to do this to restore its deterrent capability. Hamas is the weakest element in the Iranian proxy network, or one of the weakest elements. Certainly in the eastern Mediterranean it’s the weakest element because Hizballah is so powerful.

The weakest element in the Iranian alliance system just dealt Israel the worst military blow in its history. Everyone else smells blood, and they see the distance between the United States and Israel, despite the loving embrace. All of these visits that we’ve had—Antony Blinken, Lloyd Austin, President Biden—you don’t get that much attention because you’re loved. You get that much attention because there are things to be managed. They all know it. Hamas is very clever about these things. They can see it. Israel doesn’t have any friends around it that are going to go to war alongside it. The Greek allies and the Cypriot allies, they’re not going to go to war for Israel. Who’s going to go to war for Israel? Nobody but Israel.

Jonathan Silver:

In an unexpected way, we’re coming back to one of the fundamentals of the Zionist revolution and consciousness: that Israel has to assume for itself the responsibility of Jewish destiny. And at this moment, one feels that perhaps more heavily on our shoulders than ever.

More about: Gaza War 2023, Israel & Zionism, Yom Kippur War