This year, Israel marked the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, which began on October 6, 1973. As the anniversary approached, Israel’s national archive released new materials, books and articles were published, and conferences and seminars were held at which academics, generals, and veterans debated the causes of the war, its trajectory, and its consequences. Pundits offered explanations for the setbacks Israel suffered in the initial phase of the war. Suggestions were made regarding whom to blame: the government, the intelligence services, the generals, the air force, Kissinger, or Nixon.

Fast forward to this year. Early Shabbat morning, October 7, 2023, on the Jewish holiday Simchat Torah (Hebrew for “joy of Torah”), Hamas conducted a devastating surprise attack on Israel from Gaza that resulted in the worst Jewish massacres in a single day since the Holocaust and the evacuation of the largest number of Jewish villages and towns since the 1948 War of Independence. As of this writing, the war rages on, and the IDF has begun a ground offensive into Gaza. None of this would have happened had Israel’s intelligence provided an early warning about the anticipated attack, a warning that would have allowed the IDF to deploy enough troops to repel it.

Surprise is a key element of war. Since the dawn of history, every commander who led an army into battle has tried to surprise his enemy, knowing that doing so can ensure victory or at least a considerable advantage in the opening phases of a campaign. Great efforts have always been invested in deception activities to create the conditions for surprise.

The Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, as well as the Egyptian-Syrian joint offensive on October 6, 1973, were extraordinarily successful due to the element of surprise. This is where Michael Doran’s essay is wrong. However, before delving into my points of contention, I want to highlight our areas of agreement.

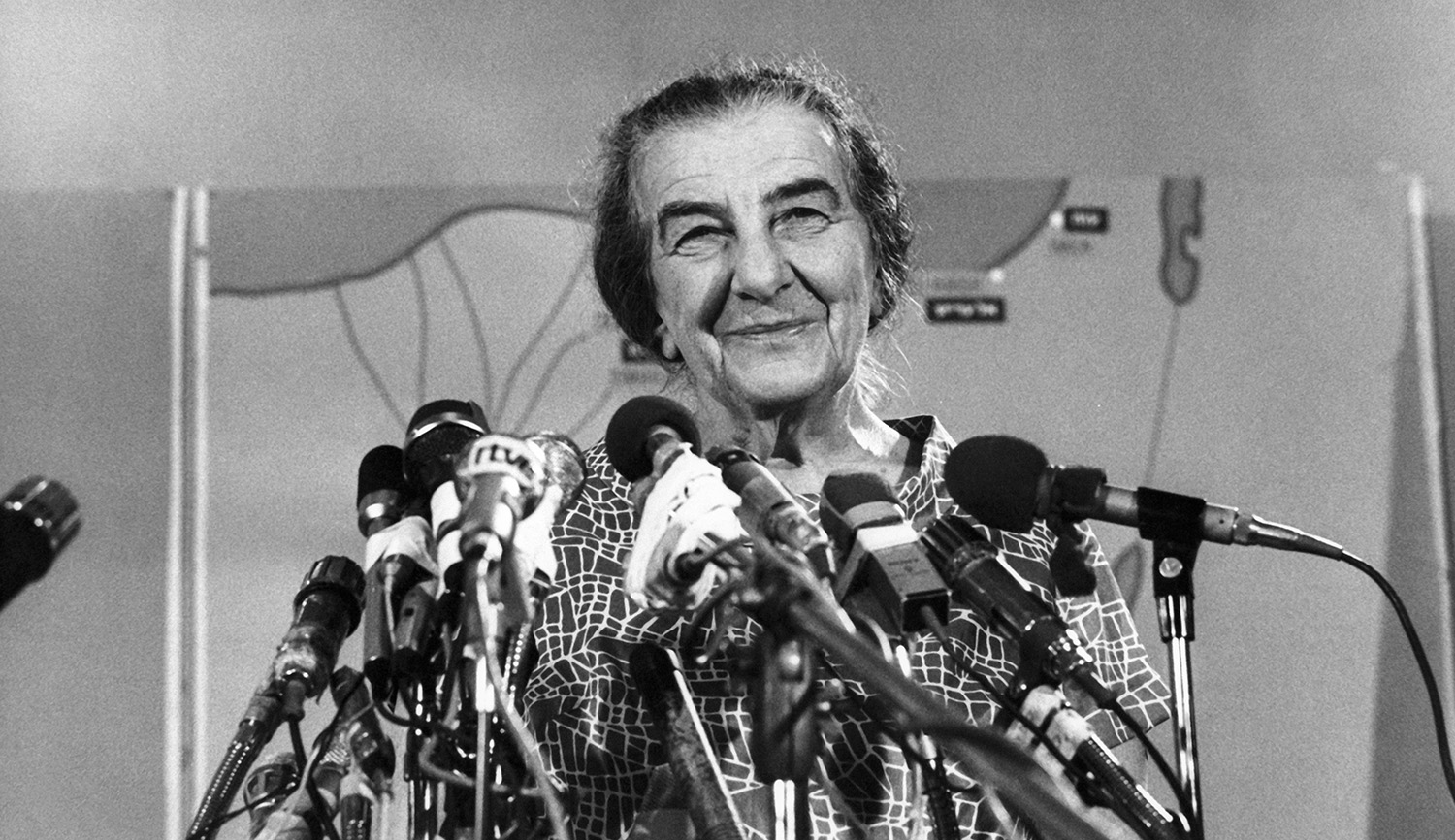

Doran’s article does a vital job by dispelling myths surrounding the Nixon administration’s role in the conflict, particularly with regard to the role of the U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger. His masterful analysis of the relations between the main protagonists in the White House, as well as between the Nixon administration and Golda Meir’s government in Israel, dispels many of the allegations mounted against both.

These allegations include the claim that Kissinger wanted Israel to bleed in order to bring it to terms after the war ended and therefore prevented it from preemption and then postponed the airlift Israel needed during the war. A more extreme, conspiratorial claim suggests that Kissinger plotted secretly with Israeli leaders to bring about an initial Arab success that would allow Egypt and Syria to restore their honor and make it easier to convince the Israeli public of the need for territorial concessions. According to this theory, the Americans and Israelis did not anticipate the Arabs militaries’ total collapse.

Doran shows that Kissinger had both Israel’s interests in mind and America’s, that he was unaware of the coming offensive, that it took time to organize the airlift and that the delays were not his fault, and that he put his brilliant strategic mind to work to try to gain the most from the situation for both Israel and the U.S. the day after.

Doran makes important contributions in two other areas as well. One is his refutation of the argument made by some historians that Egypt offered peace prior to 1973 and it was Israeli intransigence that forced Sadat to go to war. As Doran suggests, Sadat was hoping the Americans could pressure Israel to give him Sinai and otherwise withdraw to the pre-1967 borders in exchange for the promise to negotiate peace after the withdrawal, a nonstarter for the Israeli government. He also performs a great service by dispelling the myth that Israel won on the battlefield but lost at the negotiating table. Doran correctly points out that 1973 provided definitive proof that even in the worst circumstances for Israel, an Arab coalition could not defeat it. A few years later, Israel negotiated peace with Egypt, its biggest and strongest adversary, according to the terms it had demanded before the war: direct negotiations without preconditions. It was Egypt that made the bigger leap from its initial prewar conditions, not Israel.

I have two major areas of disagreement with Doran. The first concerns the impact that surprise had on Israel’s initial failures. The second is the role of Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan. I will begin with the latter.

Doran’s description of Dayan’s behavior during the war follows the line taken by many journalists and historians: that on October 7 he had (or almost had) a mental collapse and even suggested that Israel use a nuclear device. Doran repeats the rest of the narrative: that Golda marginalized Dayan after his unstable reaction and it was she and the IDF chief of staff David “Dado” Elazar who made the important decisions for the rest of the war. This narrative was created and disseminated by Dayan’s political opponents immediately after the war and uncritically adopted by most. It was recently reinforced in the Hollywood film Golda.

In the last decade, however the complete transcripts of high-level meetings have become available to the public and a very different picture emerges. Not only did Dayan not collapse on October 7, but he was the only member of Israel’s leadership to understand the entire situation and what was at stake.

The war began at 2 pm on October 6. Initial reports from the front suggested that things were going according to plan and that, despite some Egyptian successes here and there, the IDF was holding the line. Early in the morning of the 7th, reports started to arrive indicating that the Syrians were advancing on the Golan Heights. Dayan decided to go to Northern Command to assess the situation. Upon arrival, he found the front commander General Yitzhak Hofi exhausted. Hofi told Dayan the Syrians had breached the lines on the southern Golan and there were no forces with which to stop them. Dayan called the air-force commander Benny Peled and instructed him immediately to send fighter jets to stop the Syrian advance. He also made sure that the only reserve division left would be sent to the Golan.

Dayan then flew to Southern Command headquarters, arriving at noon, and was briefed by the front commander General Shmuel Gonen, who told him he could no longer hold the front and had to retreat to the mountain passes 40 kilometers east of the canal to await the arrival of the reserves. Dayan told him to choose a defensive line wherever he deemed fit.

Visiting the two fronts at their lowest point had a profound effect on Dayan. He returned to Tel Aviv deeply pessimistic about what he had seen. As far as he knew, on both fronts the defensive lines had been penetrated and the air force had failed to neutralize the enemy’s air defenses. He was unaware that at around 3 pm—hours earlier than expected— Ariel Sharon’s reserve division had arrived and the mood at Southern Command and at IDF General Headquarters had changed for the better.

When he got back from the frontlines to join the cabinet meeting, Dayan did not hide how disturbed he was. His clueless colleagues (including Golda) in the cabinet reacted with shock and disbelief. They were still expecting a Six-Day War scenario. Dayan spoke of a protracted conflict and said the IDF forces would not be able to retake the east bank of the canal. He did not suggest retreating to the middle of the Sinai Peninsula; he only stated that it was possible for the IDF to do so in a worst-case scenario, and that it could then establish a solid defensive line there. Moreover, he did not “suggest exploding a nuclear weapon,” but—according to the only testimony we have on this issue—he proposed discussing how much time and effort it would take to prepare a small nuclear device to demonstrate Israel’s capability, just in case. He also said he would accept a ceasefire if asked. It was not Golda who was worried about materiel but Dayan, who spoke of a long war of attrition and the need for men and resupply.

That meeting was later used by Dayan’s political rivals to blacken his name. However, following the failure of the counterattack in the Sinai on October 8, Dayan reestablished himself as the key decision maker. He decided with Dado to focus on the Syrian front, led the critical discussions on the crossing on October 12, and made the decision to cross the canal on October 14. He was the key player in negotiating the ceasefire with Kissinger and then led the difficult negotiations with Egypt in the weeks that followed, resisting enormous pressure to compromise Israel’s interests.

On the issue of surprise, contrary to Doran’s assertion (and he is not the first) that the surprise was less important than generally assumed, it was in fact critical to the outcome of the war. Had IDF reserves been mobilized in time, the war would have looked completely different. Instead of 177 Israeli tanks facing the Syrians on the first day of the war, there would have been approximately 600. The Syrian attack would have been a failure, unable even to enter the Israeli Golan, except perhaps for some minimal success on Mount Hermon.

In Sinai, instead of 460 infantrymen and 85 tanks defending the east bank of the Suez, there would have been three full armored divisions (approximately 850 tanks) plus a couple of infantry brigades. The Egyptians would have crossed the canal (and contrary to myth, the IDF never expected to stop them at the waterline), but their gains would have been much smaller and their casualties much higher, and they might have been thrown back rather than being able to fortify their hold on the area they captured. Even if the reserves had not reached the front in time, the regulars would have placed 300 tanks up front plus a brigade of paratroopers.

The Israeli air force also suffered two surprises: one of the war breaking out and the other of its own making. On the morning of October 6, the air force began preparing a preemptive strike, but was ordered not to carry it out. Then the air-force commander decided to change the armaments on the aircraft so that they would instead be prepared to assist the ground forces and prevent an Arab air offensive into Israel. The Arab offensive caught the air force when it was in the middle of making the switch, and thus unprepared for any of its planned scenarios. By evening, it had managed to conduct more than 100 sorties in support of the ground forces, but these were considerably fewer than planned. In other words, the surprise attack prevented the air force from operating as it should have.

Lastly, a point must be made regarding Doran’s comparison between the Egyptian use of anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles to stop the IDF and the modern concept of Anti-Access/Area Denial (or A2/AD). One should be wary of making such anachronistic analogies when it comes to military affairs. Nothing the Arabs did in 1973 really resembles A2/AD, which refers to using long-range fire to prevent the enemy from reaching the theater of war. To conduct A2/AD the Egyptians and Syrians would have needed to attack Israeli reserves advancing from central Israel to the frontlines before they came close. They did no such thing. The closest was a failed attempt by Egypt to land commandos to block the mountain passes some 40 kilometers from the canal, just behind the forward Israeli forces.

The anti-aircraft array cost Israel many aircraft, yet Israel still managed to conduct some 5,142 airstrikes on Arab ground forces and many more against strategic targets and air bases in the depths of their countries. They were definitely not denied access to the front, but their efficiency and effectiveness were reduced. Likewise, the true story of the tank-vs.-anti-tank contest is different. Nearly 1,200 Israeli tanks were damaged from all causes, but only 410 were unrecoverable—in fact, many of the damaged tanks were repaired in time to fight again.

On the subject of tanks, the majority of Israeli tanks lost in Sinai in the first 24 hours (about 200) were hit by RPG rockets and recoilless guns, not Sagger anti-tank missiles. During the first four days of the war, Egyptian infantry, with a mix of anti-tank weapons and some tanks, hit approximately 300 Israeli tanks, while Syrian tanks hit about 400 Israeli tanks. Furthermore, Egyptian human casualties were three times higher than those of the Syrians. Based on these numbers, it would seem that the Syrian tanks—supported primarily by artillery, and also by a smattering of Saggers and infantry armed with RPGs—were more effective against the IDF than the Egyptian infantry fully outfitted with the latest anti-tank weapons and supported by their own armored units.

In the end, both Arab armies failed. The Syrian army spent the last days of the war desperately fighting to stop an Israeli advance on Damascus. The Egyptian Third Army was saved from ignominious surrender by American intervention demanding an Israeli ceasefire and allowing the passage of water to the soldiers, who were cut off in the desert and had had their water supplies depleted by Israeli bombing and pipe-cutting.

The evidence clearly shows that surprise was the key element behind Israel’s initial defeat. Not only were the reserve units not mobilized, but the air force was caught unready and most of the standing army in the south was still in camps far to the rear. The war could have developed very differently if any of these IDF forces had been ready to meet the Egyptian-Syrian offensive.

More about: Israel & Zionism, Yom Kippur War