At the end of “The Restoration of the Jewish People,” his wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the tens of millions around the globe claiming some level of Jewish affiliation, Ofir Haivry declares that it’s time to get serious. Jewish institutions generally, he writes, and the state of Israel and its rabbis in particular, need to think strategically about how to respond to today’s changing modes of Jewish affinity.

I couldn’t agree more. But the first step is to ask, seriously, what it should mean to be Jewish in the 21st century.

Judaism has been described as many things: a culture, a people, a religion, a nationality, and more (including, according to answers given to the 2013 Pew survey of American Jews, a culinary disposition for bagels and smoked salmon or the possession of a good sense of humor). Let me here propose an existential minimum of what being Jewish should mean. It should mean that one’s Jewish affiliation not only forms a central part of one’s identity but also defines much of one’s actual way of life—one’s practice.

Although, sadly, the second half of this two-part premise is not shared by many Jews themselves, it has wide implications for how we think about the mass phenomenon that Haivry describes—that is, the expressed desire of untold numbers of newcomers somehow to attach themselves to the Jewish people—and about the response to that phenomenon by the rabbinic gatekeepers who in Israel determine the standards of religious conversion to Judaism.

Haivry begins by describing the two “circles” (as he calls them) of the world’s core Jewish population: namely, Israeli Jews and their counterparts in the Diaspora. Demographically, Israel is largely thriving, with a robust birthrate; by contrast, the Diaspora is suffering a numerical decline that will lead it to lose half of its numbers within the coming generation. Although Haivry does not state the fact openly, it must be acknowledged that by far the majority of those falling away are either members of one of the non-Orthodox religious denominations or, even likelier, those unaffiliated with any denomination or communal structure.

The clear lesson to be derived from this tragic phenomenon is that Jewish identity in the modern world can be maintained only by Torah or by Zion, and ideally by both. To put it another way: religion and nationalism, separately and especially together, are central to building what I’d call “serious Jews,” i.e., Jews whose way of life entails significant and regular engagement with their Jewish commitments. As various Pew reports and and recent studies of Israeli society confirm, ways of Jewish life not built around either ritual commitments or a Jewish national culture are not sustainable, at least on a mass scale. Of course there are individual exceptions—but they, however laudable and heartfelt in themselves, do not constitute a winning formula for inter-generational continuity.

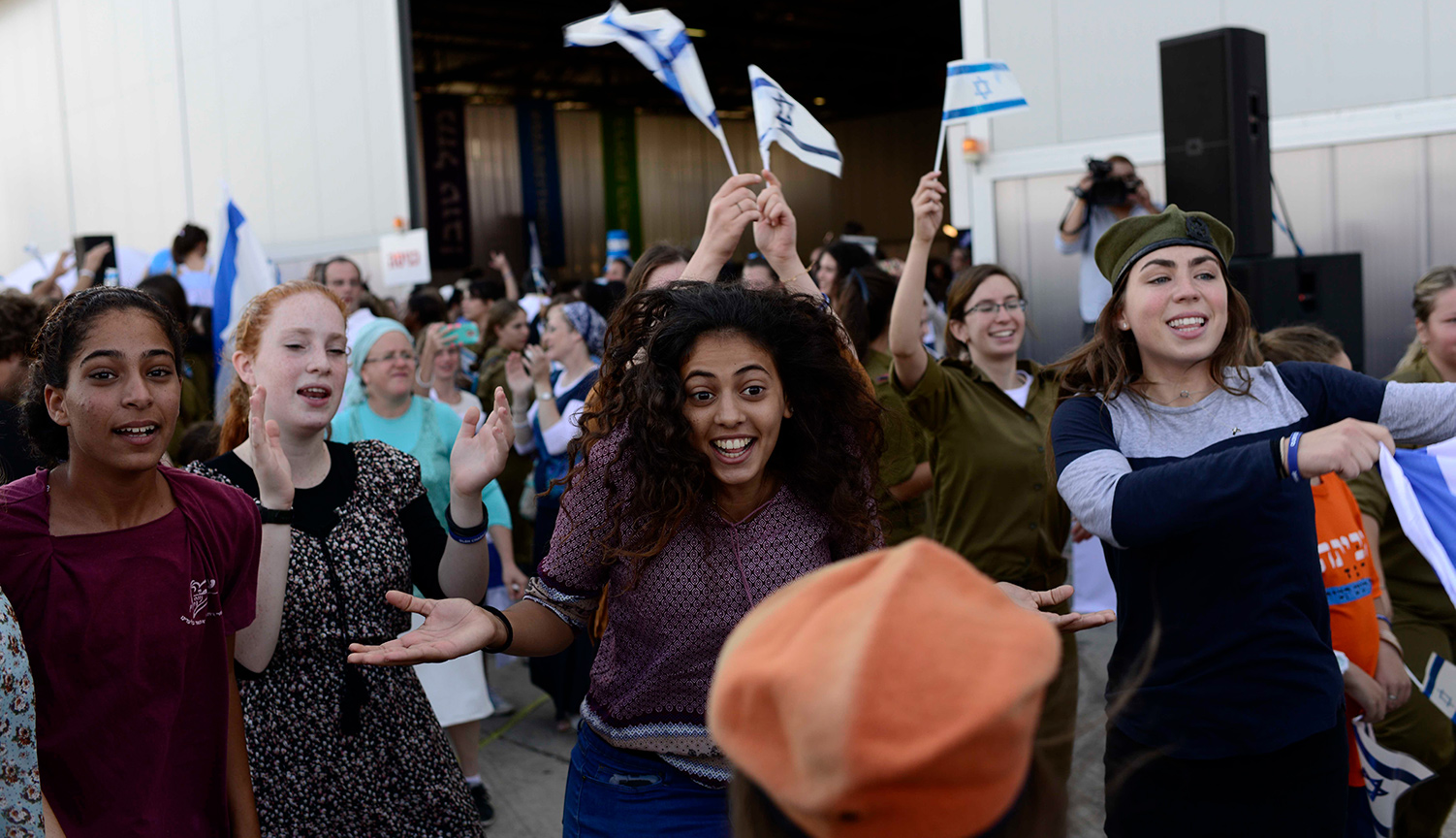

In short, if you want to develop a sustainable Jewish culture, you should build a society in which families eat Sabbath-eve meals together around a table with three or more children who are taught the crowning virtue of service in the cause of their people (like, in Israel, a term in the army or, in the Diaspora, good works undertaken for the specific advancement of Jewish solidarity).

How does this reality affect Haivry’s analysis? In particular, what will be the Jewish status of those dropping out of his first two circles? Some portion of them or their children will by definition fall into his third circle: namely, persons eligible to emigrate to Israel under its Law of Return but who may not be Jewish according to the Orthodox standards followed by the country’s chief rabbinate. That is, among their ranks will be some with only a Jewish father, a Jewish paternal grandparent, or a Jewish maternal grandfather—credentials that fail to meet the standard of matrilineal descent adhered to by the chief rabbinate.

You could argue that this is distinctly unfair, and that the state should disband or ignore the standards of Jewishness upheld by the chief rabbinate. You could also point out that few Diaspora Jews in this category are likely to seek emigration to Israel in the first place. But neither answer addresses the core existential problem facing the Diaspora itself: a community that, having conspicuously failed to keep parents or grandparents committed to a Jewish way of life, can hardly be expected to succeed with their assimilated progeny.

The same applies to those in Haivry’s fourth circle: descendants of people who converted to different religions, either by choice or under coercion. On an individual level, there will always be cases in which a formal conversion to Judaism through an Orthodox rabbinic court might be warranted, even with lower expectations for ritual observance (although this remains a matter of some debate within Orthodox circles). On a larger scale, however—and here one thinks of Latin America, where the number of people claiming and searching for their Jewish roots is quite remarkable—it’s hard to imagine how actively seeking to convert such people (or to “bring them back,” to use Haivry’s vaguer term) will accomplish anything productive. On the contrary, it could send a message that Jewish identity can be had for cheap. If, realistically, there’s little prospect that any of these individuals or groups would become serious Jews, there’s correlatively little reason to expect rabbinic leaders to relax their standards for determining Jewish status.

But now let’s narrow the focus to present-day Israel and its population of close to seven million Jews, among whom some 400,000 or so are not recognized as Jewish under Orthodox law. What are Israeli rabbis to do for those who have already been admitted by the state under the Law of Return (the terms of which, in contradistinction to those of the chief rabbinate, require only one Jewish grandparent of either sex)?

This brings us to a unique subset of people of Jewish descent in Israel who, through the simple expedient of settling in the country, have indeed built, almost by default, a significant Jewish way of life. I have in mind the hundreds of thousands of “Jewish non-Jews,” as one sociologist had dubbed them, who mostly hail from the former Soviet Union and have entered the country under the Law of Return though they do not meet the Orthodox standards of the chief rabbinate. In fact, the majority of immigrants to Israel in recent years are not recognized as Jews by that body. They are frequently the offspring of Jewish men and non-Jewish women, or at a minimum have a Jewish grandparent. Many believe they actually do qualify to be recognized as Jews under Orthodox standards (because, for example, their maternal grandmother was Jewish) but are unable prove their claim satisfactorily.

Since the 19th century, rabbis have debated whether such individuals, given their recent Jewish lineage, might be entitled to more lenient conversion standards. Lending force to such a position in the Israeli context is the very nature of the surrounding society, which naturally facilitates some form of nominal ritual observance (like eating kosher food and observing basic Jewish holidays).

Some rabbis, of whom I’m one, favor a particular step in this direction—namely, converting minors whose parents desire them to be Jewish. An organization of religious-Zionist rabbis in which I serve, Giyur K’halakhah, has achieved some limited success in this endeavor, despite a lack of support by the chief rabbinate. We regard our work as critical toward preserving the social fabric among Jewish Israelis and preventing a situation in which some Jews will refrain from marrying other, fully-integrated Israelis because of the latter’s doubtful lineage.

I don’t mean to raise unreasonable expectations. At the end of the day, conversion is an individual choice. Even if, as I hope, the state rabbinate should come to support a more lenient policy like ours, it will remain a formidable task to convince those with tangential Jewish cultural roots of the need to augment and transform their Israeli identity into an Israeli-Jewish one. This is especially true of the very significant percentage of immigrants from the former Soviet Union whose religious ties to Judaism were severely weakened by generations of life under brutal Communist rule.

And if that is the case with Russian Jews, it is all the more the case with inhabitants of Haivry’s outermost two circles. The fifth comprises tens of millions of people who, to some degree, are aware of a very distant Jewish ancestry, often thought traceable to conversos (Jews forcibly converted to Christianity beginning in the 14th century). As for the sixth circle, it typically includes groups claiming an unprovable historical connection with a long-lost Jewish community of the past. Such groups constitute a truly fascinating phenomenon, but the question remains of what exactly rabbinic leadership can do about and for them.

First, the case of each group would need to be examined on its own merits, a difficult and arduous process in itself. Second, in almost every instance cited by Haivry, rabbinic decisors agree that each individual member would be required to undergo study and conversion. (The case of the Xuetas in Majorca is a partial exception.) Third, unfortunately, these groups hail from far-flung regions that lack a strong local Jewish infrastructure. Given the general trend of Diaspora communities—that is, the trend marked by assimilation and decline—responsible rabbis will reasonably hesitate to convert members of the groups where they are now situated.

In sum, we are speaking of a real investment in resources for educating these aspiring Jews, with no guarantee that doing so would result in producing a sufficiently committed number ready for conversion, aliyah, and a potentially costly integration into Israeli society.

To Haivry, the investment is worthwhile because “encouraging the inflow of enthusiastic and committed newcomers” to the Jewish people can also energize languishing Diaspora communities around the world. Perhaps so, but it’s hard to see how that will happen. Has the admirable conversion and the wholesale move to Israel of the B’nei Moshe community of Peru inspired renewed Jewish commitments in any Diaspora community? I suspect the conversion and aliyah of the basketball star Amar’e Stoudemire, a Hebrew Israelite who found his way to Judaism, has stirred greater excitement.

Admittedly there is something tantalizing about the conversion prospects of circles five and six. Success in that realm would further strengthen and confirm the necessary conjunction of both Torah and Zion in the formation of serious Jews, a lesson that desperately needs to be absorbed in the larger Jewish world. But whether the Jewish people have either the resources or the incentive to make this possible is another matter.

Ultimately, what’s missing from Haivry’s essay is clearer expectations. If Israel is seeking to increase philo-Semitism and non-Jewish Zionism around the globe, it would be a good idea to build and maintain Israeli cultural centers in many countries. If we are thinking about conversion, let’s make sure we understand beforehand what it takes to sustain genuine Jewish commitments in the 21st century.

More about: The Jewish World