The pictures are chilling and heartbreaking: zombie-like adults passed out in the front seat of a car, overdosed on opioids, a small child belted into the infant seat in the back, safe from traffic accidents but not from his or her own parents.

America, in short, has an addiction problem. The statistics on deaths from drug overdoses collected by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)—more than a half-million people between 2000 and 2015 alone—are so appalling that one would be almost grateful to find a journalistic takedown calling them into question. Since 1999, deaths involving heroin and prescription opioids in particular have quadrupled, to the point where they constitute six out of every ten deaths from drug overdoses.

But is drug addiction the only widespread addiction? Compared with the carnage it has wrought—according to a recent study conducted by the New York Times, drug overdoses are now the number-one (!) cause of death of Americans under fifty—other forms of addiction seem relatively minor. And yet some students of the phenomenon argue that serious addiction of all kinds is much more common than we think. And these days, perhaps surprisingly, Exhibit A is addiction to technology: mainly in the form of tablets, smartphones, and online games.

To be sure, some might point to other candidates, alcoholism prominently among them. And, not to be left out of the picture, there will no doubt always be zealots of secularism eager to remind us that religion, which Marx memorably called the “opiate of the masses,” is the original and still the most prevalent mainlined drug.

In what follows, I mean to come back to the subject of religion, and specifically to Judaism (with which, notoriously, Marx had more than a bit of a problem). But to help set the stage I want first to consider Irresistible, a recent book by Adam Alter, an associate professor of marketing at New York University, who focuses on the latest form of addiction—to, in a word, technology.

I. The Deck Is Stacked

Technology, Adam Alter writes, meaning iPads and smartphones and their ilk—screens, in short—has started to produce its own class of zombies. “My mom is almost always on the iPad at dinner,” says one seven-year-old quoted in his book. “She’s always ‘just checking.’” Another seven-year-old says, “I always keep asking her let’s play let’s play and she’s always texting on her phone.” Irresistible, which displays an impressive mastery of social and behavioral psychology, captures the growing unease many others besides those seven-year-olds feel about what has been happening to the texture of their lives and relationships under the unrelenting advance of technology.

Perhaps the most disturbing anecdote in Alter’s book, aside from the one about young Chinese videogamers who wear diapers so they can play nonstop—“that’s why they call it ‘electronic heroin,’” comments a Chinese psychiatrist—comes from another young person, this one a seventh-grader quoted in a Washington Post story. As the social life of her peers has moved online to social media, the girl reports, “I’m not doing anything childish. . . . At the end of sixth grade I just stopped doing everything I normally did. Playing games at recess, playing with toys, all of it, done.”

In Alter’s view, this girl and the rest of us never really had a fighting chance. In order to understand why, he invites us to expand the way we typically think about addiction. According to the conventional wisdom, addicts are a distinct class of people who are inherently prone to this intense form of compulsion; these are the people who lose their lives to drugs and alcohol. Yet Alter walks the reader through a large body of social science suggesting that everyone, at some level, is capable of becoming an addict under the right circumstances.

For example: in the early 1970s, the Nixon administration was braced for the eventual arrival of 100,000 heroin addicts in the form of American soldiers coming home from Vietnam. To nearly everyone’s surprise, 95 percent of these soldiers reintegrated into life in the United States and remained clean. It turns out that in Vietnam, under intense stress and with a ubiquitous and cheap supply, these soldiers had indeed turned to heroin. But only temporarily: once back in normal American circumstances, without the stresses of battle and the easy availability of cheap heroin, most dropped the drug and got on with their lives.

But the new world of addictive technology, Alter maintains, is indeed the equivalent of ubiquitous “electronic heroin,” and it is bringing out the latent addict in large parts of contemporary society. The feedback mechanisms of social media are engineered to erode self-control. Serial videos and TV shows are designed to foster binge-watching. Fitness trackers encourage compulsive exercise. Video games have become so powerfully addictive that Bennett Foddy, one of Alter’s colleagues at NYU and himself a game developer, won’t play World of Warcraft. “I take it as part of my job to play all the culturally relevant games,” Foddy explains, “[b]ut I didn’t play that one because I can’t afford the loss of time. I know myself reasonably well, and I suspect it probably would have been difficult for me to shake.”

According to one study cited by Alter, 41 percent of the population has at least one behavioral addiction—and that survey was taken in the prediluvian age of 2011. Remember 2008? Back then, adults were spending an average of eighteen minutes a day on their phones. By 2015, the average had jumped to two-and-three-quarter hours. Alter cites Tristan Harris, a former “design ethicist” at Google: it isn’t that people lack willpower, but “there are a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job it is to break down the self-regulation you have.”

In other words, the deck is stacked against us.

II. Modes of Recovery

Alter is a thoughtful observer and an engaging storyteller, and his book is an important attempt to flash a caution sign as we race ahead to destinations unknown. But it also suffers from a significant limitation. His worldview seems to be a closed box: if something can be described and analyzed by psychology and the social sciences, it is worthy of discussion. Otherwise, it hardly enters the frame.

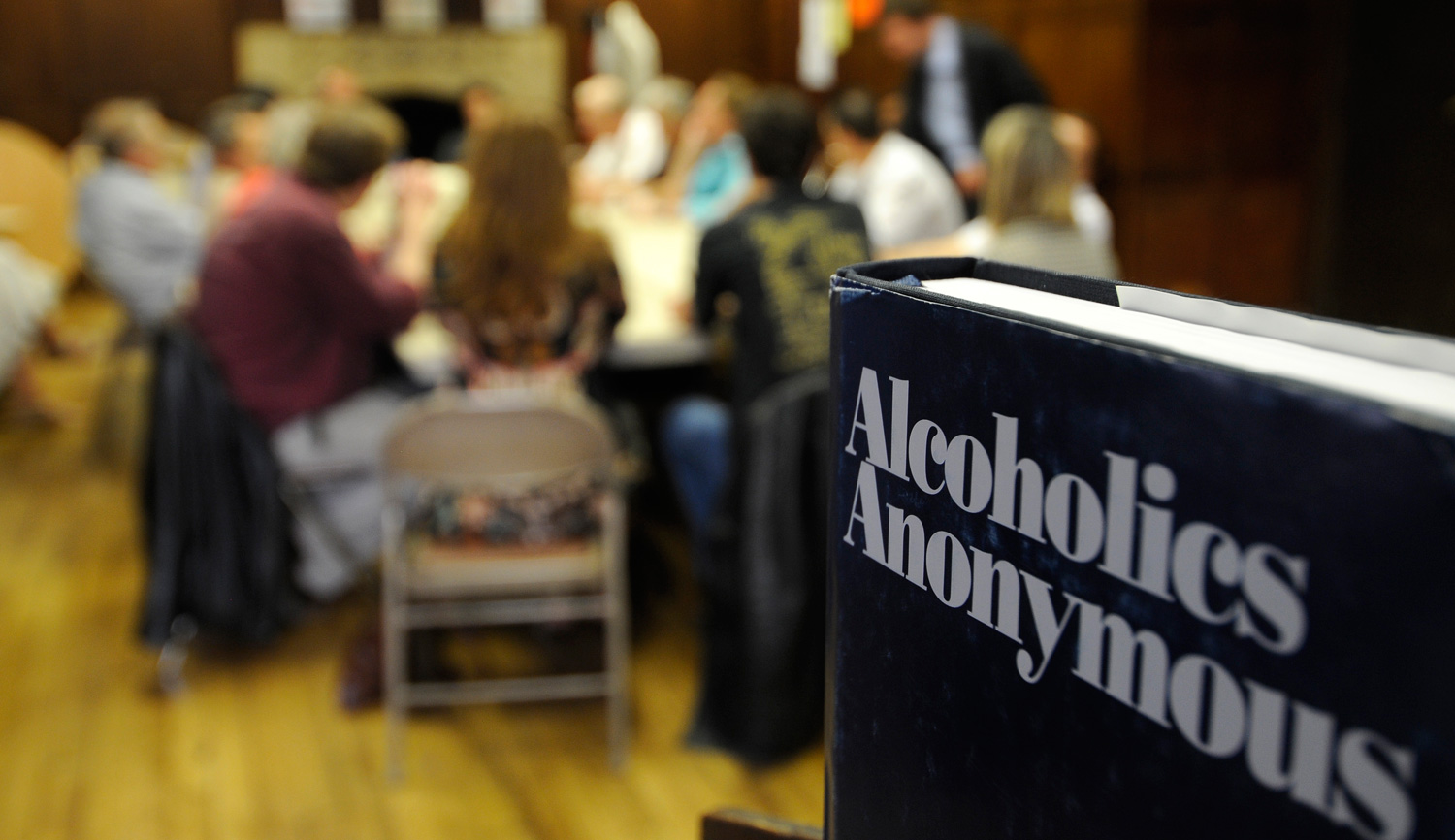

Hence the absence of any serious discussion in Irresistible of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), whose founders in the 1930s were arguably the first to achieve some success in facing the problem of addiction head-on. Since then, AA’s now-famous program of twelve-step recovery has been adapted to a wide range of behavioral addictions beyond alcohol abuse: to name but a few, addiction to food, sex, gambling, and spending. So the mere fact that twelve-step recovery hardly comes up for discussion in Irresistible amounts to something of an implicit dismissal.

Early in the book, the reader learns that the psychologist Stanton Peele has offered a sustained critique of AA’s “disease” model of addiction. Later on, AA is mentioned briefly as promoting total abstinence and suggesting that, in contrast to other modes of therapy, addicts are otherwise helpless to overcome their compulsive behavior. So, in Alter’s telling, the twelve-step fellowships associated with AA have little if anything helpful to say to the large numbers of people struggling with behavioral addictions connected to the use of technology.

Peele, introduced by Alter as one of the thinkers who helped develop the very idea of behavioral addiction, is an interesting figure in his own right. With polemical gusto, he has taken aim at all of AA’s sacred cows: the disease model of addiction, the idea of the addict’s powerlessness, the concept of hitting bottom before being able to acknowledge that powerlessness, the consequent need to turn over one’s will and life to the care of a Higher Power. To Peele, public policy would be wise to break from the AA party line and embrace alternatives that work better for most people.

Gabrielle Glaser, writing in the Atlantic last year, leveled a similar critique. Why, she asks, are policy makers and addiction experts still tied to AA’s outdated twelve-step paradigm when modern science has shown other methods (like naloxone therapy for alcoholism) to be more effective? She quotes Thomas McLellan, a psychology professor and former deputy U.S. drug czar: “Alcohol-and-substance-use disorders are the realm of medicine . . . not the realm of priests” (emphasis added).

Fair enough: policymakers should embrace the most effective treatment methods, and one can leave it to AA advocates and their critics to go on debating the relevant issues. More interesting (at least to me) is what McClellan means by the “realm of priests”—to which, for the sake of diversity, we can add rabbis and imams. What are the implied theological underpinnings of Alcoholics Anonymous? Is there a segment of the addict population that really does need what twelve-step recovery has to offer? Does the non-addict population have anything to learn from its experience?

In answering these questions, it helps to revisit the founding of AA in the 1930s. To borrow a contemporary term, Alcoholics Anonymous was “crowd-sourced”: through a process of trial and error, a group of alcoholics located in Akron, Ohio and involved with the Oxford Group, a Christian fellowship popular at the time, came up with a program of recovery that worked for them and others.

In the late 30s, this cell of recovering alcoholics broke off from the Oxford Group and formed Alcoholics Anonymous. In 1939, it published Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How More Than One Hundred Men Have Recovered from Alcoholism, widely known in recovery circles as the “Big Book.” Written by AA co-founder Bill Wilson in consultation with the early members, the Big Book outlined AA’s approach to the problem of alcoholism and its solution.

Early on in the Big Book, Bill Wilson tells the story of Rowland Hazard. With his Yale degree and a secure place within a wealthy Rhode Island family, Hazard was one of those people who seemed to have it all. Unfortunately, he was also an incurable alcoholic. The good news was that he could get the best care money could buy: treatment with none other than the famed Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. But that treatment didn’t work, either, and so Hazard asked Jung to tell him the “whole truth”: why did he have no control over alcohol, and what could he do about it?

Jung replied to both questions. Hazard, Jung concluded, had the “mind of a chronic alcoholic,” and Jung had never met anyone in that chronic state who was able to recover from it. He did, however, hold out one ray of hope. Wilson paraphrases the psychiatrist’s message to his patient as follows:

Exceptions to cases such as yours have been occurring since early times. Here and there, once in a while, alcoholics have had what are called vital spiritual experiences. To me these occurrences . . . appear to be in the nature of huge emotional displacements and rearrangements. Ideas, emotions, and attitudes which were once the guiding forces of the lives of these men are suddenly cast to one side, and a completely new set of conceptions and motives begins to dominate them.

In fact, I have been trying to produce some such emotional rearrangement within you. With many individuals the methods that I employed are successful, but I have never been successful with an alcoholic of your description.

In 1961, once AA was well established, Bill Wilson wrote what he referred to as a long-overdue letter of appreciation to Jung, citing his treatment of Rowland Hazard (who later came in contact with the early members of AA) as the “first link in the chain of events that led to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.” As it happens, Wilson himself had had some sort of sudden, intense spiritual experience—later he joked that his more cynical AA friends called it his “hot flash”—and found himself released from the obsession to drink. The 1941 second printing of the Big Book included an appendix on the nature of such experiences while also making the point that recovery from alcoholism didn’t necessarily depend on a sudden transformation. In fact, a wide range of spiritual awakenings was occurring within AA, and most of the eventual transformations they heralded were of the kind that the philosopher William James called “educational,” unfolding slowly over a period of time.

In responding to Wilson’s letter of appreciation, Jung wrote that he had actually pulled his punches in discussing alcoholism years earlier with Rowland Hazard:

His craving for alcohol was the equivalent on a low level of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God.

How could one formulate such an insight in a language that is not misunderstood in our days?

The only right and legitimate way to such an experience is that it happens to you in reality and it can only happen to you when you walk on a path, which leads you to a higher understanding. You might be led to that goal by an act of grace or through a personal and honest contact with friends, or through a higher education of the mind beyond the confines of mere rationalism.

And Jung went still farther:

I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition, if it is not counteracted either by real religious insight or by the protective wall of human community. An ordinary man, not protected by an action from above and isolated in society, cannot resist the power of evil, which is called very aptly the Devil. But the use of such words arouses so many mistakes that one can only keep aloof from them as much as possible. . . .

You see, alcohol in Latin is spiritus and you use the same word for the highest religious experience as well as for the most depraving poison. The helpful formula therefore is: spiritus contra spiritum.

III. Getting Unstuck

The ordinary moral vocabulary of most people today doesn’t contain words like “the union with God” or references to the “devil.” These, as Jung noted, are indeed medieval terms. But it is hard not to see some glimmer of contemporary reality in Jung’s portrait of the “ordinary man” unprotected by a connection to God or a larger community, struggling to resist the power of evil whether in the form of alcoholism or in some of the other compulsive behaviors catalogued by Adam Alter.

After all, it is precisely the possibility of a God-based spiritual counterforce that most seems to provoke the ire of critics like Stanton Peele. As Peele writes, heatedly:

When addiction is seen to be a disease [as in AA], something that clearly cannot be treated from within, you must turn yourself over to recovering addicts and alcoholics and addiction experts—and, most famously, to a “Power greater than ourselves,” in order to become whole again. What a pernicious, anti-humanistic idea! From this perspective, any efforts you make for yourself prove that you are foolish, stupid. Is there any more denigrating statement in the addiction field than, “Your own best thinking got you here?” Where but in a twelve-step room or support site would this mantra be considered therapeutic or helpful?

Between AA and its critics, then, one almost senses the outlines of a theological debate turning on first principles. Rejecting the “pernicious, anti-humanistic idea[s]” of AA, the critics view all addictive behaviors through the lens of humanistic/scientific/materialistic axioms; to deal with these behaviors, they then prescribe a set of humanistic/self-help/behavioral/psychological solutions. For example, a videogamer who is fulfilling his deeply human need for community online should focus on acquiring real-world friends. Smartphone addicts should restructure the “behavioral architecture” of their lives by building habits that militate against the addictive use of technology. Alcoholics, Peele writes, should concentrate on “redirecting [their] life and thinking” by means of mindfulness exercises and meditation.

Twelve-step recovery, by contrast, delivers a very different message. If the addict starts with an openness to the possibility of God, or if the severity of his addiction has forced him to become open to that possibility, then he can see all of his addictive behavior in a spiritual light and search for a vital spiritual experience as the solution.

So there is really an argument here. Still, my own sense is that AA’s program and non-AA methods are speaking to two different kinds of addicts—as, to be fair, Alter himself seems aware. And on these grounds one can sympathize with his approach. If individuals can solve their problems on their own, without a vital spiritual experience, by all means they should do so. Take, for example, people who struggle with obsessive checking of their email at night; simply changing the location where they charge their phone (nowhere near the nightstand, for starters) can provide the behavioral nudge toward a solution of the problem. They don’t need twelve-step recovery.

But what about addicts for whom the only way out is a vital spiritual experience, whether of the sudden-flash or slow-educational variety? At the end of the day, Alter and Peele and Glaser are limited, however proudly, to the realm of medicine and science. But that toolbox, as powerful as it is, appears to falter when faced with the Rowland Hazards of the world. These addicts force us to ask the question—to the extent we admit it is a question—of whether science adequately explains the full spectrum of the human condition. Or is there a certain point on that spectrum at which we have to pivot from science and medicine to, in brief, the realm of priests and rabbis?

“Is there any more denigrating statement in the addiction field,” Peele (to repeat) asks caustically, “than ‘Your own best thinking got you here?’ Where but in a twelve-step room or support site would this mantra be considered therapeutic or helpful?” The answer to his dismissive rhetorical question: where but in church (or in synagogue).

The real addict comes to see that life without God simply doesn’t work for him. This is a realization that one person cannot preach into another person. It can’t be taught. It is an insight that one can only come to on one’s own. How, then, can one get there? If you have a life-or-death need for a vital spiritual experience, with its attendant “large emotional displacement” by which one set of ideals, emotions, and attitudes are exchanged for a new set, where and how do you find it?

A hint might be found in Jung’s description of the spiritual experience itself: it happens to a person when he walks a spiritual path. One can import too much meaning into this turn of phrase, but it does seem to capture something true about spirituality. It can’t be forced. The addict might not be able to find God on his own. Other people can’t find God for him. But God apparently can find the addict. Where, and when? For most full-blown addicts, the answer is pretty simple: when they have reached bottom.

“Ego collapse at depth,” as Bill Wilson describes it elsewhere in his letter to Jung, makes room for God to enter the picture. The twelve-step program begins with the admission of powerlessness. The first step reads: “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.” When an addict truly hits bottom—when life shows him, conclusively, that all of his efforts to manage his own life have utterly failed—then he is ready to declare bankruptcy, so to speak, on his own existence as a going concern and turn it over to new management.

“Because of your conviction that man is something more than intellect, emotion, and two dollars’ worth of chemicals,” Bill Wilson wrote at the end of his 1961 letter to Jung, “you have especially endeared yourself to us.” As Jung wrote back, however, even to talk of such things is to be misunderstood.

IV. Enter Judaism

“The really amazing fact about AA,” wrote Wilson, “is that all religions see in our program a resemblance to themselves.”

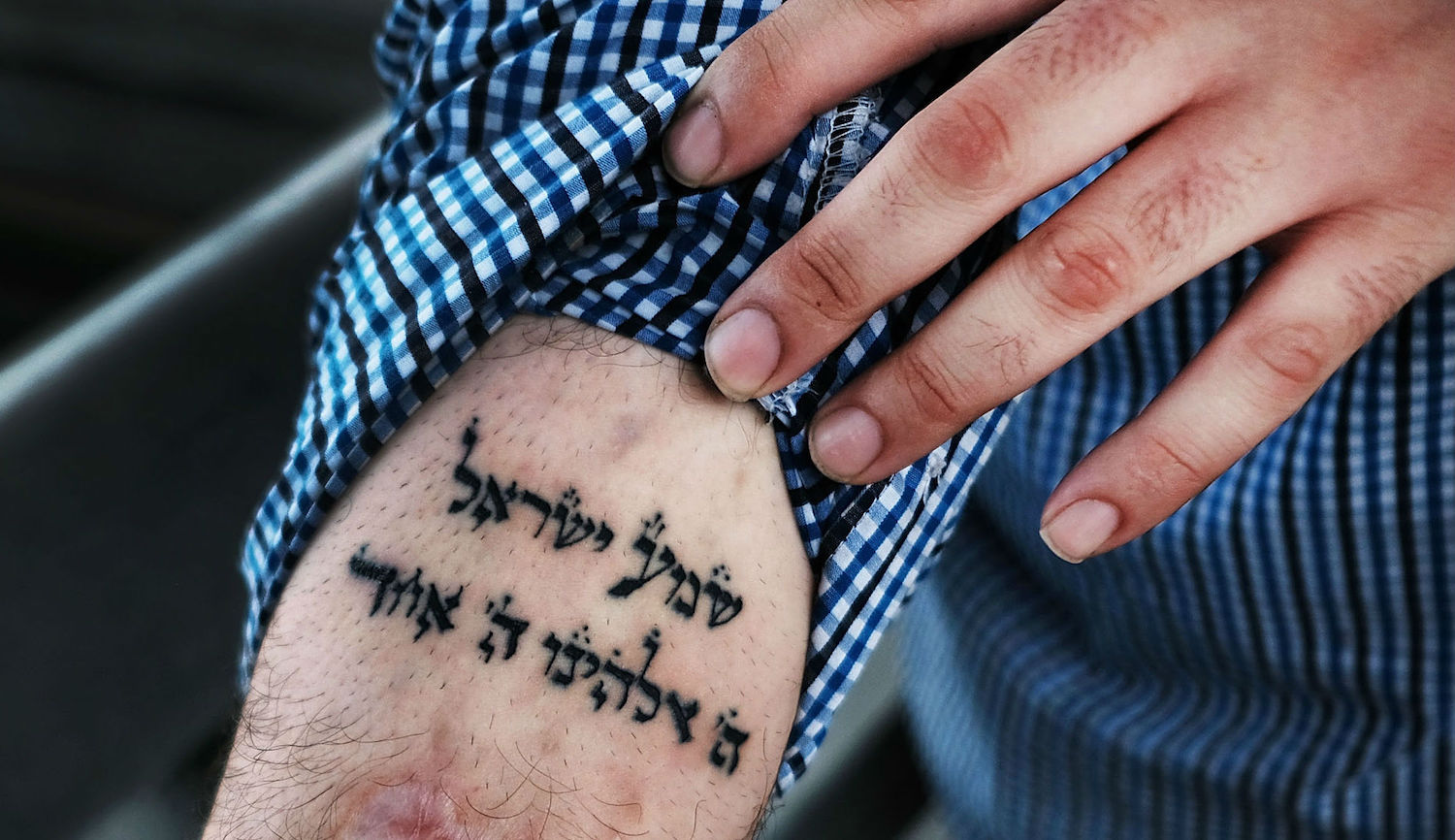

One of those religions is Judaism, and many Jewish addicts have been surprised to find themselves reconnecting to the God of their fathers in, of all places, twelve-step meetings held in a church basement. But on reflection we shouldn’t be too surprised. Abraham Twerski, a ḥasidic rabbi and the founder of a rehabilitation center in Pittsburgh, has long argued for the compatibility between AA and Judaism, and Rabbi Shais Taub’s God of Our Understanding amounts to a theological study of the twelve steps from the perspective of Judaism.

What these and other thinkers point out is that Judaism is a subtle blend of belief and action, with the emphasis on the latter. Moreover, as recovering addicts like to emphasize, one of the pivotal chapters in the Big Book is called “Into Action,” not “Into Thinking” or “Into Philosophizing.” The Big Book stresses the need to align one’s will with God’s will; for Jews taking their own faith seriously, this inevitably leads to thinking about their relationship with Jewish law, halakhah, which presents itself as just that: the practical, actionable repository of God’s will for man.

And there’s more to it than that. There is the whole Jewish story itself—which, without much effort, can be heard as something resembling the first recovery narrative. Indeed, a strong resemblance can be seen between the trajectory of the addict from enslavement to freedom and the twinned Jewish holidays of Passover, commemorating the exodus from Egypt, and Shavuot, celebrating the giving of the Torah seven weeks later at Mount Sinai. Traditional Jewish thinkers have noted that the Hebrew word for Egypt, Mitzrayim, is related to the word in Hebrew for “limitation,” as in Psalm 118: “From the straits [min ha-meytzar] I called God.” Who is more enslaved than the addict to the limitations of his own personality? Whose ability to function is more essentially constricted within the “straits” of his own character defects?

“My own best thinking is what got me here.” Stanton Peele might rail against the “anti-humanism” of the thinking behind that slogan, but the refrain of many addicts in recovery attests otherwise. Someone whose best thinking has truly landed him in the hole of addiction can’t “self-help” his way out. The internal resources to do so have been exhausted and found lacking. “Many of us had moral and philosophical convictions galore,” writes Wilson in the Big Book, “but we could not live up to them even though we would have liked to. Neither could we reduce our self-centeredness much by wishing or trying on our own power. We had to have God’s help.”

In The Choice to Be, Rabbi Jeremy Kagan argues that what caused the Israelites to hit “bottom” in Egypt was the Pharaonic order that they gather the straw to make bricks. Building is hard work and necessitates both concentration and rest, but straw is light and can be gathered constantly and as it were robotically (not unlike the way a person can spend time endlessly clicking from website to website). In this reading, the constant gathering of straw caused a disintegration of the Israelites’ personalities, essentially forcing God to remove them from Egypt while there was still something left to remove.

Which is another important point: the Israelites didn’t go out of Egypt on their own power. They were removed from Egypt by God. Yes, they had to make themselves available for redemption by offering the Passover sacrifice and putting its blood on their doorposts. They had to do something—to start walking a spiritual path. In Egypt, the process started with their “crying out.” But then God did for them what they could not do for themselves. Or, as another pithy twelve-step slogan has it: “Without God, I can’t. Without me, God won’t.”

Having been given their freedom, the Israelites started the journey to Mount Sinai where they would receive the Torah. Like most addicts new to recovery, they were shaky, and wanted nothing so much as to return to what was familiar and comfortable: “If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by pots of meat, when we ate bread to our fill!” But they made it. Or, to paraphrase the third of the twelve steps, they made a decision to turn their will and their lives over to the care of God. They were free, but now they had a purpose: acceptance of the Torah. Mount Sinai began the educational process that, according to the 19th-century rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch, is the underlying drama of Jewish (and, for Hirsch, world) history.

Ernest Kurtz, the late historian of AA, once wrote that “alcoholic” is but “human being” writ large. In other words, the addict presents an exaggerated version of certain fundamental human problems. At some level, every person struggles with his ego and character defects, but for the addict this struggle has become a matter of life or death.

“Alcoholics Anonymous works,” Kurtz writes,

not because it is new but because it makes available an ancient wisdom. For other peoples, in earlier times, that healing wisdom was made available by other vehicles. The religion of the churches, immersion in classic literature, a sense of belonging to a community that was greater than and had claims on the individual: each of these experiences, in general no longer available to most of us, afforded a healing that facilitated living with the imperfection of the human condition.

The hard part, alas, is the actual living with the imperfection of the human condition. As a friend of mine once put it in reflecting on people (like myself) who find religion later in life, it’s one thing to be “born again,” but you still have to grow up. Which is to say that Sinai—revelation alone, a single burst of inspiration —isn’t enough. As Rabbi Akiva Tatz has pointed out, the trials of the Jews in the desert after the revelation at Sinai served that very purpose of growing up:

[O]nce saved, once inspired, once made conscious of our higher reality, the price must be paid, the experience must be earned, and in working to earn the level that was previously given artificially, one acquires that level genuinely.

While it might be uniquely challenging to “grow up” today, it is fair to say that the problem is an old one, going back at least to the experience of the Israelites at Sinai.

For moderate addicts, one can hope that the behavioral solutions offered by Adam Alter will be sufficient. But if they aren’t, the less moderate might have something helpful to share with the rest of us as we try to navigate the brave new world of smartphones, virtual reality, and whatever else tomorrow brings. As technology progresses faster than do our coping mechanisms—and as the pain of living with the imperfection of the human condition becomes more and more acute—we may need to find better ways of satisfying our bedrock spiritual needs than the ones we are currently using or the ones that modern medicine, psychology, and behavioral science can prescribe.

In this perspective, Adam Alter, who describes the problem with admirable clarity, is a bit like a weatherman who, after forecasting a tsunami, helpfully reminds his audience not to forget their umbrellas. If “alcoholic” is but “human being” writ large, it may be that everyone from the opioid addict to the teenager (or adult) hooked on his phone would benefit from a different set of tools, derived from twelve-step recovery and reflected in Judaism’s master narrative.

More about: Addiction, Arts & Culture, Politics & Current Affairs, Religion & Holidays