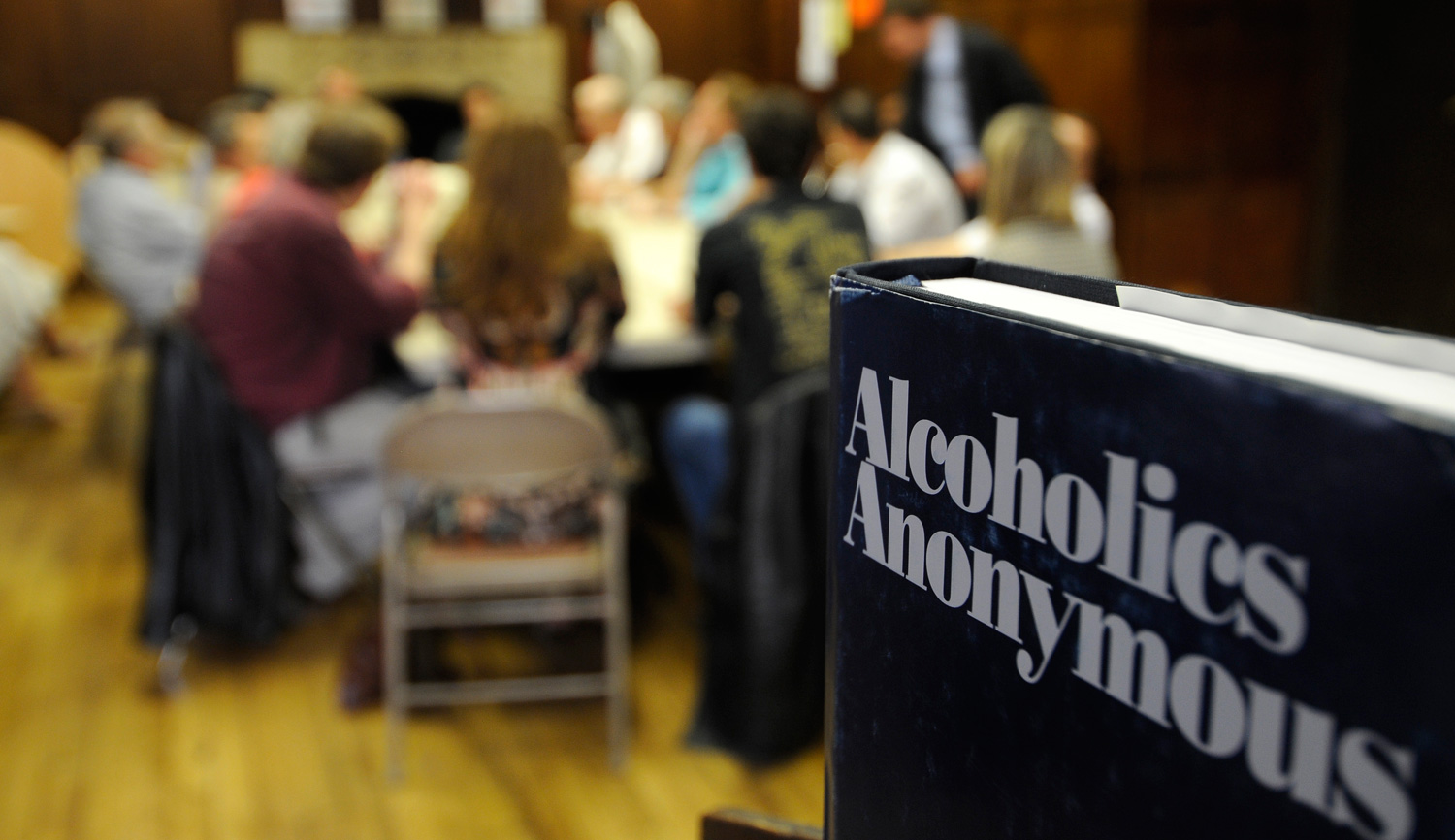

In “God, Religion, and America’s Addiction Crisis,” Jeffrey Bloom confronts head-on the fact that many contemporary experts have little use for Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its foundational presumption that addicts can find help from a “higher power.” Instead, these critics of AA would limit the study and treatment of addiction strictly to the realm of medicine and brain science.

And yet, as Bloom notes, science and medicine are visibly failing with what is now acknowledged as a huge epidemic of opiate addiction and drug-induced deaths in America. In this light, he asks whether science does indeed adequately grasp “the full spectrum of the [addict’s] human condition, or whether there is a certain point on that spectrum where we have to pivot from science and medicine to, in brief, the realm of priests and rabbis.” He concludes his essay on a similar note, urging that “as the pain of living with the imperfection of the human condition becomes more and more acute,” we turn to “better ways of satisfying our bedrock spiritual needs than . . . medicine, psychology, and behavioral science can prescribe.”

As a psychiatrist interested in behavioral disorders of many different kinds, let me offer my support to Bloom’s analysis and make a suggestion—springing directly from nature, and based on those same “bedrock needs”—that might help justify a God-aware approach to treatment.

My suggestion begins with a fundamental question raised by the theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Erwin Schrödinger in a series of lectures given in Dublin in 1944 (and promptly turned by him into a book). “What is life?” Schrödinger asked. His answer is of intrinsic interest and high relevance.

Living things, Schrödinger proposed, can be distinguished from non-living things by their capacity to “keep going” and thereby “postpone” the inevitable decay into the inert state of physical entropy that is the endpoint of every system: essentially, a passive thermodynamic equilibrium in which no further observable events occur or can occur.

By analogy from Schrödinger, I hold that psychiatrists, for their part, should ask the question, “What is human psychological life?” And I would answer similarly, by proposing that human beings are characterized by being mentally productive and responsive in ways that support both them as individuals and the communities within which they dwell. With help from many sources, most humans grow from their beginnings as selfish, willful, ignorant, and emotionally incontinent children into competent, coherent, and cooperative adults who at their best bring about, through thought and action, changes that advance opportunity and flourishing for all. Just as their bodies keep going physically, they keep going psychologically.

How are these two kinds of keeping-going, the physical and the psychological, accomplished? Or—perhaps better for our particular purposes here—what defers entropy, whether the physical entropy of the lifeless or the “psychic entropy” displayed in the arrested development, loss of freedom, incoherence, and despair of the addicted?

In describing just how living things sustain themselves physically, Schrödinger noted that “matter is said to be alive . . . when it goes on . . . exchanging material with its environment” for energy and sustenance. But in this exchange not just any sort of matter—think of carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen, etc.—is suitable for the living, and neither is any sort of collected matter that, like an unburned lump of coal or a diamond, might happen to harbor energy within.

Rather, Schrödinger observed, living organisms need to find matter that, like actual food, is organized in such a fashion that its ingestion and digestion bring energy to keep physical entropy at bay. Food is quite simply “organized stores” of accessible energy. The operative word is “organized.”

Again by analogy, humans as they develop their plans and mold their futures keep psychic entropy at bay by drawing on organized stores of social purpose and direction—with “organized” being once more the operative word. These organized stores range from the purpose-laden information and skills learned in school to the most complex principles of understanding, cooperative interaction, and integrity gathered from a culture by those living in it.

Where exactly are some of those complex principles to be found? How did they develop? In what way are they organized for incorporation into the mind—and (again for our purposes here) how might they be reorganized into the mind of someone stuck in the psychic entropy of addiction? No better example can be found than AA’s classic Serenity Prayer, derived from the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. In that prayer—“God, grant me serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference”—rests an organized store of purposefulness capable of addressing and challenging addictive psychic entropy.

In AA, this sort of “God talk” challenges the theophobia of many contemporary social scientists and experts on addiction. But where else than within the great traditions of our religions do we find the most cogently organized stores of principles for living? Those traditions also enjoy the great advantage of having been tested by time and survived as kinds of “evidence-based” prescriptions for today. Another great advantage is that they are accessible to psychological life.

This is not to claim that no other sources of principles for psychological flourishing exist. Primary among those other sources are the mediating structures of society: in particular, families, schools, and the workplace. Often, in treating an addict, a psychiatrist will discover that for some reason—either deprivation or distraction—he or she has lacked, neglected, or ignored those resources. Tellingly, these matters, too, are addressed in AA’s “organized stores”—its twelve steps—and such supplementary versions of psychotherapy as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) draw upon them.

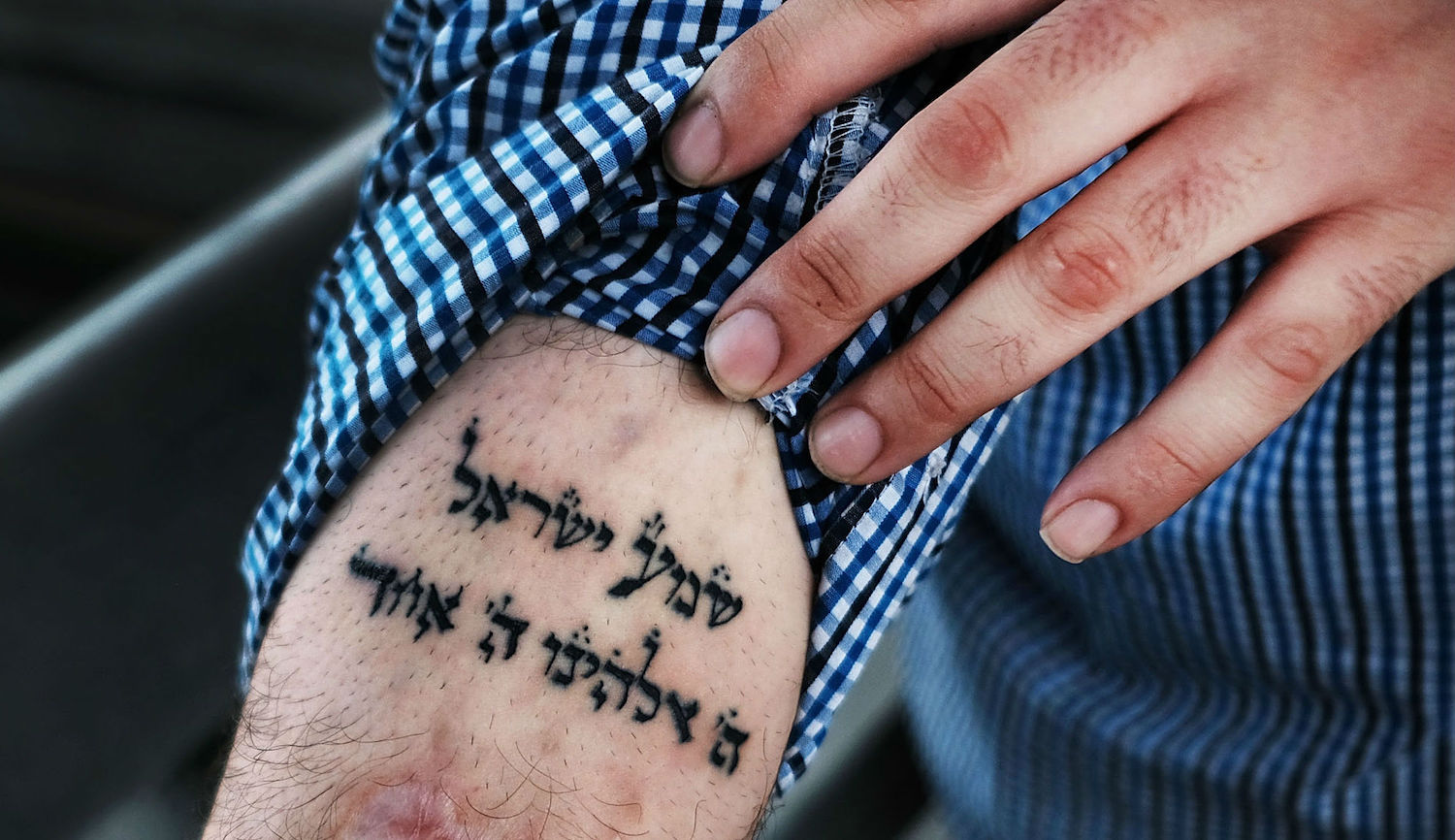

Which brings us back to Jeffrey Bloom. In defending the “priestly” role of AA, he calls our attention to the thought of several contemporary rabbis who have noted the resemblance between the twelve-step pilgrimage from addictive slavery to freedom and the foundational Western narrative of the exodus, that is, the freeing of the Israelite slaves from Egypt and ultimately their receiving at Mount Sinai the Torah that is the pathway to their flourishing as a people.

Those resemblances are striking. No one who has attended both AA meetings, where members recount their personal experiences of struggling with an unmanageable existence dominated by alcohol or drugs, and Passover seders, where in story, song, and commentary the participants relive the experience of the Israelites moving out from under the Egyptian yoke, can miss the likeness. Surely the multi-millennial survival of the Jewish people as a stubbornly resolute and creative community despite dispersal, persecution, and genocide must likewise be tied in part to their embracing the principles in the Mosaic law that stress both individual integrity and responsibility to God and neighbor.

From its start, AA has championed addicts incorporating the organized stores represented by Hebrew scripture. Jeffrey Bloom salutes that approach and its pertinence to the treatment of addiction today. For all that this fits so well with nature itself, I’m with him.

More about: Addiction, Arts & Culture, Religion & Holidays, Science, Secularism