Martin Kramer’s new essay in Mosaic is the most recent installment in a series by him reconsidering the events surrounding Israel’s declaration of independence in May 1948. As with its predecessors, the present essay, focusing on the military issue, has much of interest to say, though I fear that in the end it is less significant than his prior contributions.

The first Arab-Israeli war—which transformed the geopolitics of the Middle East—ran from November 1947 until July 1949, when the last of the armistice agreements between the newborn state of Israel and its Arab neighbors was signed. It roughly consisted of two parts: a civil war, from November 1947 until mid-May 1948, between the Arab inhabitants of Palestine (who later came to call themselves “Palestinians”) and the country’s Jewish community, followed by a conventional war, from May 1948 to July 1949, between the state of Israel and the neighboring Arab states.

The civil war began on November 30, 1947, with sporadic attacks by Palestine Arab militiamen on their Jewish neighbors. Some 1,700-1,800 Jews were eventually killed in that war. The conventional war began with the invasion of Palestine/Israel by armies of neighboring Arab states on May 15, 1948.

As an aside, Kramer somewhat misrepresents the situation at the start of the conventional war by writing that “five regular Arab armies” had massed on the border “intent on invading and crushing the Jewish state.” Israeli historians have now more or less agreed that, of the five, the Lebanese army never crossed the border and the Jordanian army (also known as the Arab Legion) harbored no intention of “crushing” Israel and never invaded its territory. True, the Israelis and Lebanese did clash when Israel invaded Lebanon, and the Jordanians and Israelis clashed repeatedly around Jerusalem, which had been designated an international zone by the UN partition plan of November 29, 1947. But only the Egyptian, Syrian, and Iraqi armies crossed the border and attacked Israel, possibly with the intention of “crushing” the new state.

As for what was happening internally on the Israeli side, which is his major topic, Kramer enters the fray by focusing on the May 12, 1948 meeting of the People’s Administration, the thirteen-man body (with only ten attending) that was the pre-state cabinet of the yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. At that meeting—which took place exactly at the mid-point of the war’s two halves—the People’s Administration consensually agreed to the declaration of Israeli statehood three days hence, on May 15, when the British mandate government, which had ruled Palestine since 1917-1918, was due to evacuate the country.

Here, Kramer zeroes in not on the issue of the declaration itself, covered at length in his previous essay in Mosaic, but on the statements at the May 12 meeting of the People’s Administration by the two chiefs of the Haganah, the yishuv’s militia: Yigael Yadin (Sukenik), the organization’s head of operations and de-facto commander in the war, and Yisrael Galili, its political commissar or, as he was called, the head of the Haganah national staff. These two men, who had been summoned by Ben-Gurion to report on the military prospects, declared bluntly, and for some attendees startlingly, that if the neighboring Arab armies invaded as they had promised to do (and as they would do on May 15), the yishuv’s chances of winning the war stood at “fifty-fifty” or “were even.”

Kramer, deploying lengthy quotations, seems in this essay to be arguing that Ben-Gurion wanted the Haganah chiefs to give this prognosis—which was not only depressing but contrary to his own view that, simply put, the yishuv would win the war. He did so, Kramer writes, in order to bolster his own status as the yishuv’s supreme and confident leader (no defeatist, he!) and especially to help him in his months’-long effort to enhance his personal control over the Haganah, which he regarded as in no way prepared for the expected pan-Arab invasion.

In doing this, Kramer belittles the Haganah and seriously misrepresents the history and evolution of the yishuv’s defense forces. Let me elaborate.

Kramer fails to tell his readers that by May 12, despite occasional lapses, the Haganah had thoroughly defeated the Palestine Arabs, destroying their militias, conquering most of their towns, and uprooting hundreds of thousands from their homes. By that date, Palestine Arab society had been crushed and the yishuv had won the civil war hands-down. Instead, Kramer concedes merely that the Haganah and its strike force the Palmaḥ had by then “scored some real victories.” This downplaying of the yishuv’s victory in the civil war is designed implicitly to endorse Ben-Gurion’s own dismissal of the Haganah and its brass as ineffectual.

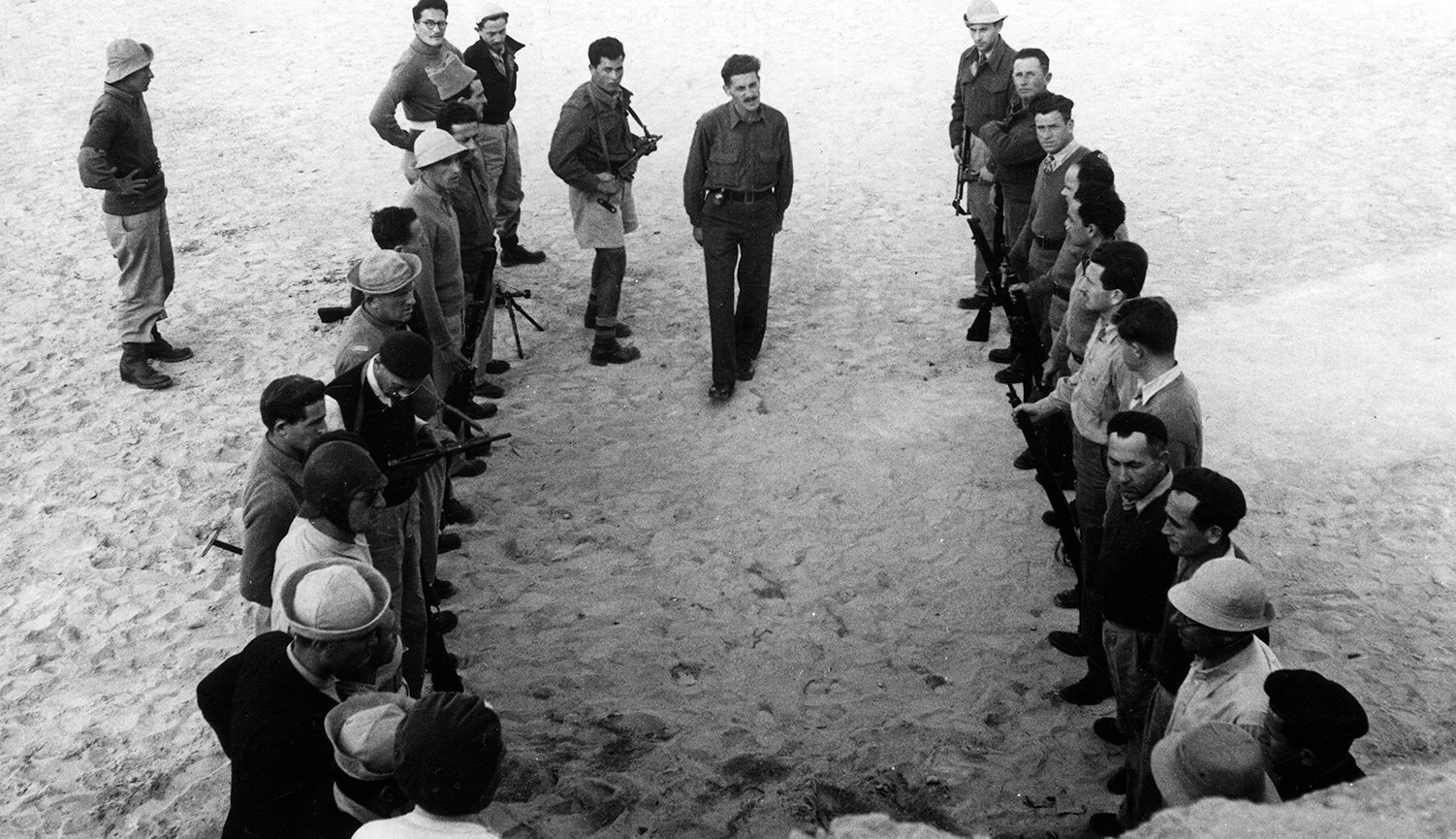

A little background is warranted here. The Haganah—the milita established in the 1920s and in effect the military affiliate of the yishuv’s labor movement and its socialist parties and organizations—had expanded substantially over the decades. By the end of 1947, it comprised some 30,000 members, about 3,000 of whom were in the Palmaḥ, its shock companies (elite formations).

Relevant here is another point. Kramer speaks in passing of other, “factional militias” in the yishuv that Ben-Gurion was resolved to break and unify under a single command. This is not quite right. Since 1937, the right-wing Revisionist movement had its own armed affiliate, the Irgun Tsva’i Leumi (National Military Organization): a terrorist or urban guerrilla group numbering by 1947 some 2,000-3,000 members. There was also a splinter group called Leḥi (Freedom Fighters of Israel): a combined force of some 300-500 extreme right-wingers and extreme left-wingers united under the banner of driving out the British occupier. But neither the Irgun nor the Leḥi was a militia. The only militia was the Haganah.

Since 1947, Ben-Gurion, who in December 1946 had taken over the defense portfolio of the Zionist Organization/Jewish Agency, had been privately telling everybody of his unhappiness with the Haganah’s structure and leadership and of his determination, with an eye toward impending war with regular Arab armies (which he rightly anticipated), to establish a “regular,” British-style army alongside the Haganah or to re-organize and convert the Haganah into such an army.

The Haganah, Ben-Gurion said, might suffice for small-unit guerrilla operations and for defending Jewish settlements, but not for full-scale combat against regular armies. At a minimum, he sought to replace many of the home-grown Haganah commanders with experienced Palestine Jewish veterans of the Allied armies in World War II. (During that war, some 28,000 Palestine Jews had served in the British Imperial army alone.)

For their part, the Haganah chiefs, preferring their own internally, homebred officers, resisted and sporadically clashed with Ben-Gurion over his efforts to force upon them veterans of the British or other Allied armies. His appointments included such figures as Dan Even, Shlomo Shamir, Shalom Eshet, and Ephraim Ben-Artzi.

This, in any event, was how Ben-Gurion then and later would present his struggle with the Haganah command before and during the 1948 war, and this, in effect, is how Kramer presents that struggle. But there was also another level to Ben-Gurion’s struggle and machinations during this period, and one that Kramer basically underplays. It was the level of politics—specifically, party politics.

Already during 1946-47, Ben-Gurion resented the dominance in the Haganah, and especially in the Palmaḥ, of officers affiliated with Aḥdut Haavodah (Unity of Labor) and Hashomer Hatsair (Young Guard): two socialist parties that in January 1948 would be amalgamated into Mapam (United Workers). Among those officers were Yisrael Galili, Yitzḥak Sadeh, Eliahu Ben-Ḥur, Shimon Avidan, Yigal Allon, Moshe Carmel, and Yitzḥak Rabin.

The competition represented by these parties to his own party, Mapai (Land of Israel Labor), which he had founded and led since 1930, deeply alarmed Ben-Gurion. The war with the Arabs enhanced that worry, since the high reputation of the Haganah in the yishuv and its prospective victory in war might vastly increase the popularity in the polls of Mapam, which stood to the left of Mapai. Very few senior Haganah commanders were linked to Mapai.

Who knows, Ben-Gurion occasionally asked in explaining his September 1948 closure of the Palmaḥ’s separate headquarters, but the Mapam boys might even mount a coup and seize power at war’s end? And indeed, in the years after 1948, he took care to eject ex-Palmaḥ officers from senior posts in the IDF. (Ironically, after his departure from the premiership and defense ministry, the Palmaḥ veterans Rabin, Haim Bar-Lev, and David Elazar became successive IDF chiefs of staff.)

In truth, Ben-Gurion was wrong on all points. The Haganah had actually prepared well both for the civil war against Palestine’s Arabs and for the subsequent conventional war against the Arab armies. And that explains why the yishuv won the 1948 war.

Starting in November 1947, the Haganah began to re-organize itself as a proper army, shedding its character as a loosely centralized territorial militia. By March 1948 it boasted proper “battalions” and the beginnings of brigade formations; by May 1948, it fielded ten brigades, albeit not yet fully equipped; on June 1, two weeks after the declaration of statehood, it changed its name to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Aside from the name, however, nothing else changed. The general staff’s departments and branches, the brigades, the battalions, even most of the commanders—all were as they had been in the Haganah a week or two earlier. And this general staff and its field formations did the job. First, in May-June 1948, they managed to contain the invading armies. Next, in a series of offensives over July, October-November, and December-January they succeeded in driving back and/or beating the Arab armies, forcing them to cease hostilities and sue for an armistice.

In the end, the army that won the 1948 war was largely commanded by the original, homegrown Haganah officers, from Yigael Yadin on down. These commanders and their reorganized, retrained, and re-equipped “militia” units had swiftly turned into “regular” formations. And together they accomplished exactly what Ben-Gurion had long argued they could never do.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Haganah, History & Ideas, IDF, Israel & Zionism