Rick Richman describes the story of Theodor Herzl as a “mystery.” Was it? To some degree we are all mysteries. No human can ever fully understand another—or, for that matter, him or herself. Herzl was a particularly complicated man whose neuroses were commensurate with his talents. But complexity is the opposite of mystery—it is an invitation to empirical investigation and a caution not to take our subject’s self-presentation, or his perception by others, at face value.

Many Zionists of Herzl’s era agreed with Richman’s comparison between Herzl and Moses. The artist Ephraim Lilien depicted him as Moses, the prince of Egypt who rejoined and redeemed his people, and as other biblical heroes such as Aron and Joshua. In his diary, Herzl likened himself to Moses, striving to lead a “procession of slaves.” However meaningful it was for Lilien and Herzl to make these comparisons, however, they should not form a typology of Jewish leadership because biblical figures are not necessarily historical ones. Even if we believe that Moses and Joshua existed, we cannot access their deeds, thoughts, and feelings beyond what an ancient sacred canon tells us. This is not the case with Herzl, a modern man who left behind a vast trove of literary, journalistic, and personal writings. Also, Herzl’s contemporaries recorded their interactions and impressions of him, throwing light on not only his leadership ability, acumen, and charisma but also his character flaws, blind spots, and failures.

Herzl’s turn to Zionism was the product of many factors. Richman emphasizes encounters with anti-Semitism in Paris and especially Vienna. But many European Jews of Herzl’s era were confronted by anti-Semitism, while few became Zionists. We must look as well to Herzl’s life-long aspirations for achievement and recognition. At the age of twenty-three, in the wake of his resignation from the Albia fencing club, the unhappy end of a love affair, and the rejection of his first plays, Herzl wrote that he was “overcome by the hopelessness of my existence. . . . Yet I need success. I thrive only on success.” Such feelings are common in adolescence, but depression, and the desperate search to relieve it via nonstop work and achievement, continued to afflict Herzl throughout his adult life.

By the early 1890s Herzl had attained modest renown as a playwright, with plays performed in New York and Prague, and, on occasion, at the prestigious Burgtheater in Vienna. Unfortunately, his artistic talents were limited, and Herzl knew as much, comparing himself unfavorably to his far more gifted friend, Arthur Schnitzler. Herzl did, however, achieve fame as a master of the feuilleton—a kind of long-form journalism in fin-de-siècle Central Europe that encompassed fiction, short plays, travel essays, and social and political commentary. In the spring of 1895 Herzl became the literary editor (and highest-paid staff member) of Central Europe’s most prestigious newspaper, Die Neue Freie Presse.

Herzl came to this appointment after four years as the newspaper’s Paris correspondent. Fluent in French and possessed of wit and charm, Herzl rubbed shoulders with France’s greatest writers, artists, and politicians (including Émile Zola, Gustav Flaubert, Auguste Rodin, and Georges Clemenceau). Upon his return to Vienna, Herzl was befriended by two of Austria’s prime ministers, who appreciated the value of having the ear of a sympathetic journalist. Yet none of this was enough for him. Trapped in a miserable marriage, and frustrated by the daily grind of journalistic work, Herzl searched for a way out. He dreamed of owning his own newspaper.

There was more, however, to Herzl’s brewing existential crisis than careerist ambition and familial dysfunction. While at university studying law and political economy, Herzl had developed a deep concern with the condition of the industrial working classes—what was known at the time as the “social question.” In 1890, and again in 1892, Herzl stated his conviction that “the Jewish Question” was an “arm of the great stream, which is called the Social Question. But great streams cannot be artificially separated, and when the snow melts on a spring day, the floods dig, tunnel, and rip their own way.” Herzl saw the Jews as contributing to anti-Semitism through their concentration in trade and finance. A socialist revolution, which would put an end to the capitalist system in which both Jewish economic particularity and anti-Semitism thrived, both attracted and repelled Herzl. At the time he floated his scheme for a mass conversion of Austria’s Jews to Catholicism, he was toying with calling upon Germany’s Jews to become ardent socialists. It is no coincidence that Herzl’s 1894 play Das Neue Ghetto, his first major work to deal explicitly with anti-Semitism, was also about the appalling conditions of the mining industry.

In the spring of 1895, Herzl fell into an agitated mental state that Richman refers to as a “frenzy” emanating from “a mysterious source, like a voice in the night.” It certainly was a frenzy, but it may also well have been an episode of mania, especially given Herzl’s life-long struggle with depression. Although some of his writing from this period is enthralling and illuminating, much of it is unnerving and disturbing. It combines flashes of paranoia and prescient wisdom, megalomania and altruistic idealism, delusions of grandeur and canny self-awareness. Herzl presents himself as the chief organizer of Jewish mass migration. He is a dramaturge whose actors are the Jewish masses in Eastern Europe and whose stage is the future Jewish state. Jewish mass migration will solve both Europe’s Jewish and Social Questions. Herzl had indeed, as Richman writes, found his calling, but it was more than that. It was the tonic that gave him a reason to live, and the glue that cemented his fragile persona.

How did Herzl find his way from the authorship of a small pamphlet to the leadership of the global Zionist movement? Richman calls Herzl a “man from nowhere” in the Jewish world, but that appellation is not wholly accurate. Not only was Herzl an influential and well-known individual in Europe, he was also very much part of the Central European Jewish bourgeoisie of the time. His newspaper was edited by two assimilated Jews and attracted many Jewish readers. The tolerant and liberal society that Herzl depicts in his 1902 novel Old-Newland epitomized a Jewish fantasy of what their own countries were or should be. In childhood, Herzl had attended a Jewish school for several years and at least occasionally went to synagogue services with his father in Budapest’s Dohany (in German, Tabak) Street synagogue. He knew some Jewish history and a bit of Yiddish (e.g., meshugge). None of these facts lessens the cultural gap separating Herzl from his East European Zionist colleagues, but Herzl was not a complete stranger to them. More practically speaking, given Herzl’s celebrity and relative wealth (his father was comfortably well off, and his wife Julie’s dowry was worth the equivalent of $1.25 million today), it is hardly surprising that he quickly became a major figure in Zionist circles.

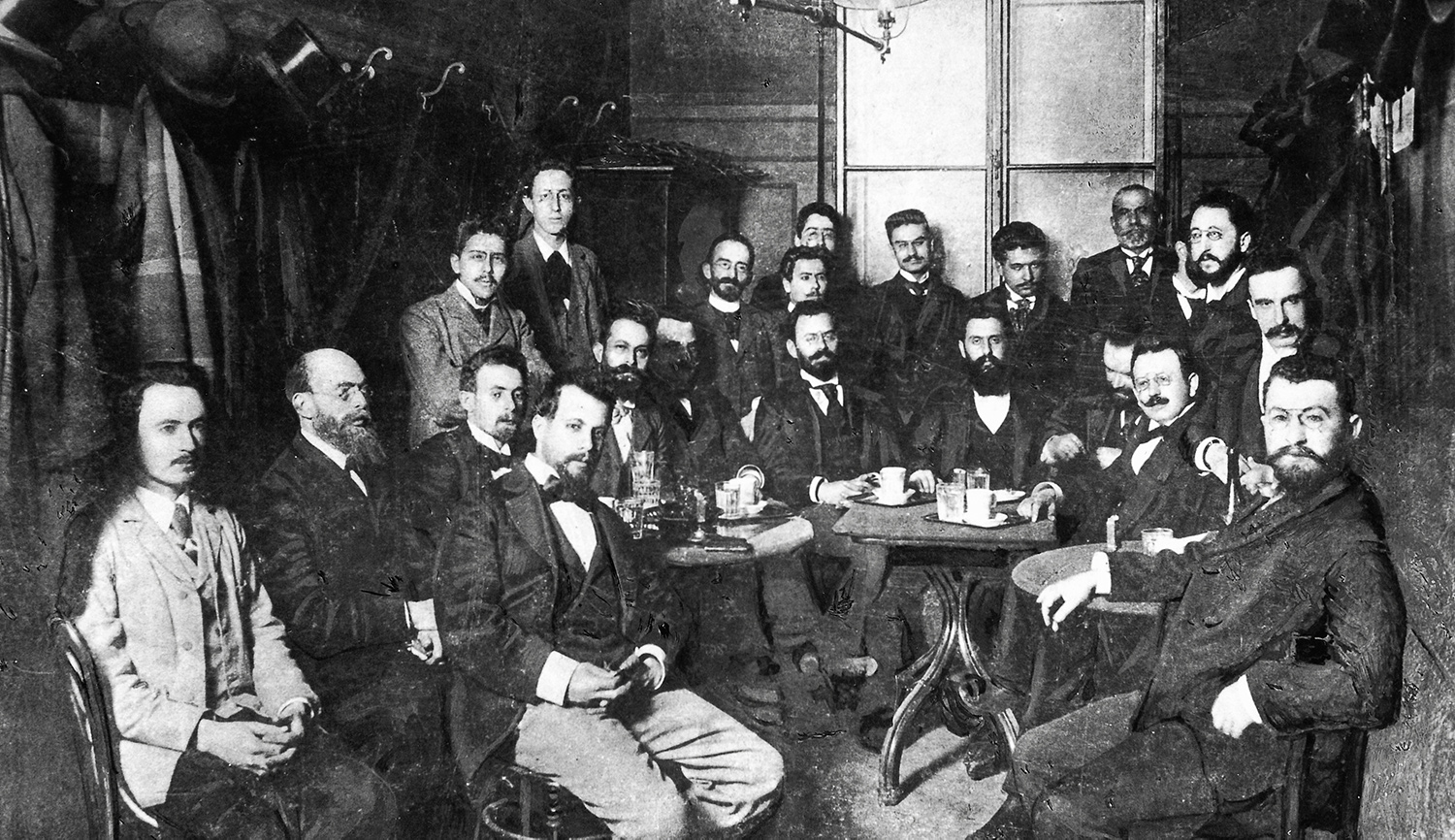

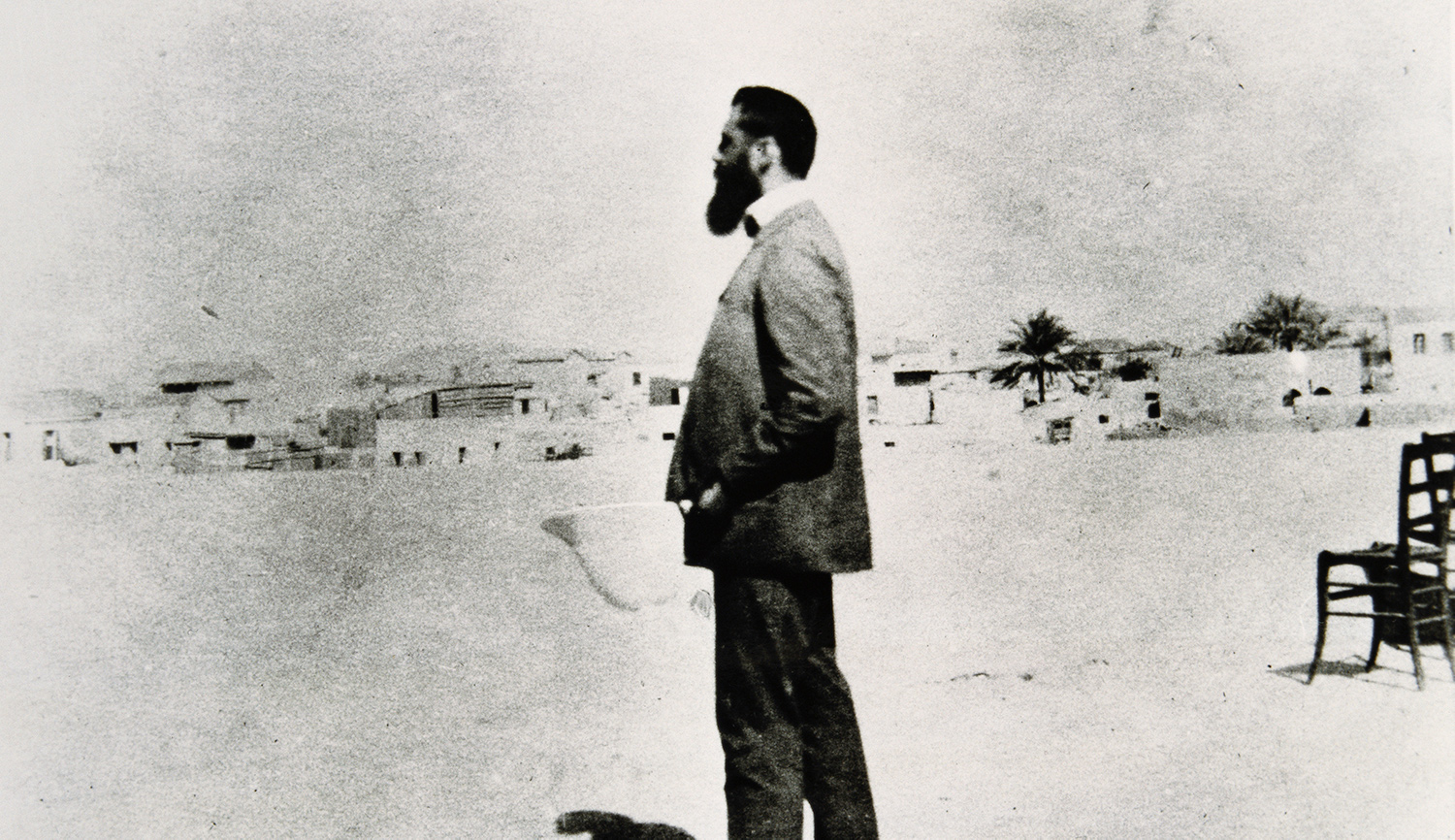

Herzl’s rise to the top of the Zionist leadership was enabled as well by his indefatigable work ethic, well-honed administrative skills, and, perhaps most of all, his mesmerizing appearance and stately carriage. Herzl may not have been a latter-day prophet, but he certainly looked the part. Some of his appearance was unscripted (e.g., his dark, sunken eyes), but Herzl cultivated an air of biblical majesty via his beard, which he first grew during his years in Paris but which became fuller and more luxuriant over time.

Two additional aspects of Richman’s account deserve comment. First is its reverence and avoidance of assessing Herzl’s shortcomings. Herzl was a great leader, but he had significant character flaws. Aloof and self-centered, he was prone to outbursts of arrogance born of profound insecurity. Herzl could be as cruel to his wife Julie as she was to him; he was an absent father who misremembered his children’s ages. In his dealings with fellow Zionists, Herzl was often high-handed, condescending, and rude. (He could be especially, and unjustly, harsh to his loyal lieutenant, David Wolffsohn.) Herzl’s writings are sprinkled with misogyny, and at the First Zionist Congress he assumed that women would have no right to speak or vote. (At subsequent congresses Herzl had to acquiesce in the face of overwhelming opposition from male and female activists alike.)

Herzl’s political judgment was not always sound. His views on the Middle East were shot through with orientalist stereotypes and double standards. He accused the Ottoman leadership of duplicity, but Herzl was treated just as shabbily by the German Kaiser, whom Herzl unstintingly adored. Herzl was aware of Arab opposition to British rule in Egypt, but he refused to consider the likelihood of Arab resistance to mass Jewish settlement in Palestine, even when this was pointed out to him, politely but firmly, by a former mayor of Jerusalem, Yousef Dia al-Khalidi.

Herzl’s flaws were those of a man possessed of vision, ambition, and iron will. Those attributes account for Herzl’s many successes as creator of the Zionist Organization and the public face of Zionism on the world stage. Herzl’s successes were not, however, of the “biblical proportions” that Richman attributes to them. Herzl’s diplomacy with Europe’s great powers accomplished little. So long as the Ottoman empire stood, no Zionist leader could gain Palestine for the Jews. The British offer of territory in East Africa almost split the Zionist movement in two. Three years after its founding, the Zionist bank that Herzl created had raised barely a quarter-million pounds in share capital.

Nonetheless Herzl gave the Zionist movement structure and visibility. His Zionist speeches and writings inspired scores of thousands of Jews during his lifetime and millions more in the decades after his death. Chaim Weizmann would in most ways be a more successful leader than Herzl and would live to see the creation of the state of Israel. But it is Herzl’s face—dark, somber, and filled with mystery—that has adorned offices and classrooms throughout the Jewish world. Herzl was what Hegel called a world-historical individual, a shaper of human affairs. Yet he was filled with inner turmoil, and the contradictions between what he was and what he wanted to be—and between the Jewish world as it was and what he wanted it to be—brought him to an untimely end.

More about: Israel & Zionism, Theodor Herzl