In Rick Richman’s insightful essay “The Mystery of Theodor Herzl,” he describes Leon Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation: An Appeal to His People by a Russian Jew (1882), which argued powerfully for the establishment of a Jewish state. After noting that David Ben-Gurion called it “the classic and most remarkable work of Zionist literature,” Richman explains that it nonetheless failed to arouse support as its author “traveled to Austria and Germany in search of Jewish leaders to support his ideas—and found none at all. . . . Faced with no significant Western reaction to his book, Pinsker concluded dispiritedly in 1884 that it would take the messiah—or ‘a whole legion of prophets’—to arouse the Jews.”

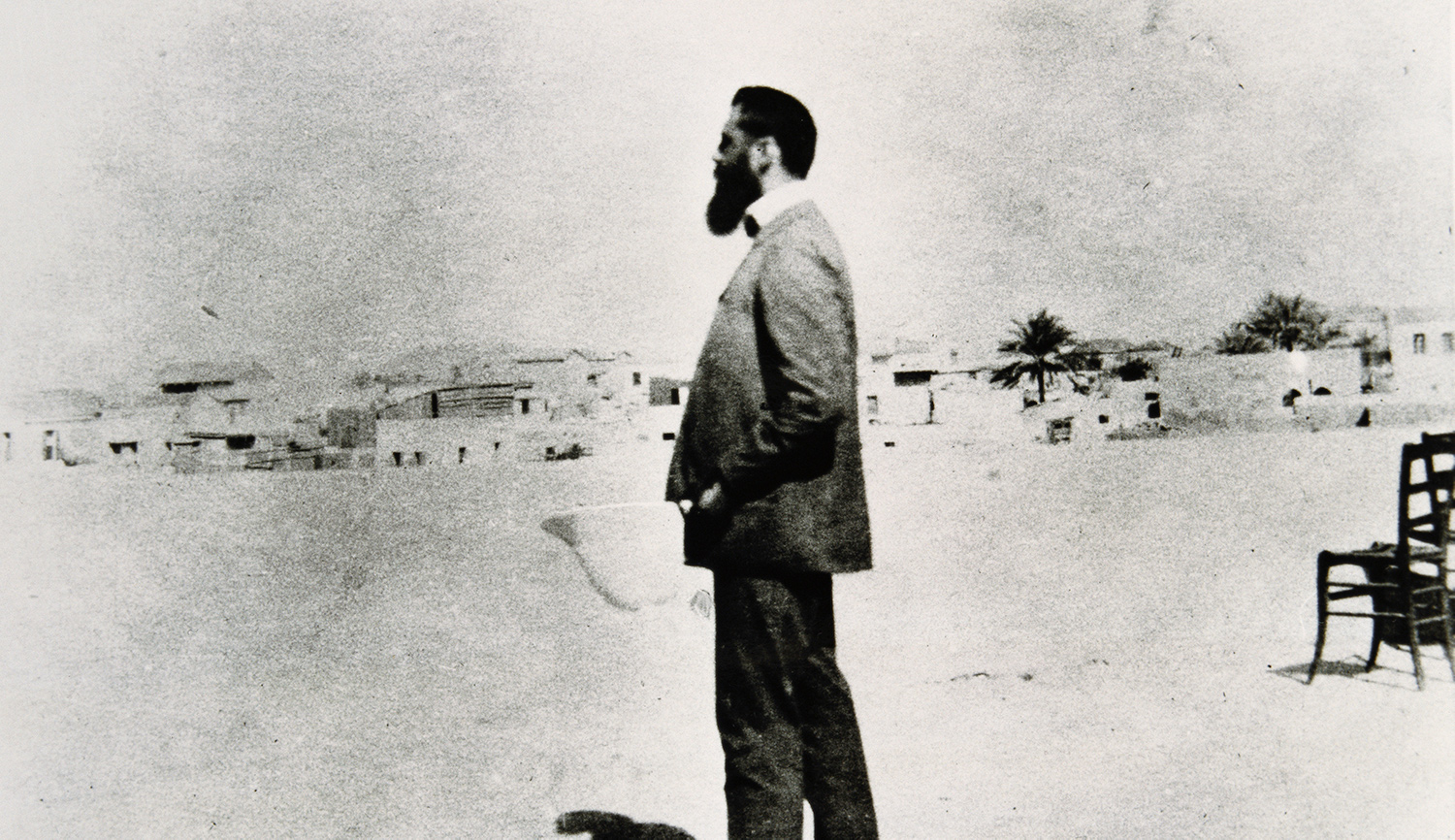

Richman devotes the bulk of his excellent essay to describing, in starkly different terms, Theodor Herzl’s success, beginning with the bold declaration: “Not since Moses led the 40-year Exodus from Egypt did anyone transform Jewish history as fundamentally as Theodor Herzl did in the seven years from the publication in 1896 of his pamphlet The Jewish State to his historic pledge in 1903 on the subject of Jerusalem at the Sixth Zionist Congress.” As Richman argues, Herzl, more than anyone else, is responsible for creating the Jewish state that arose four decades after his death.

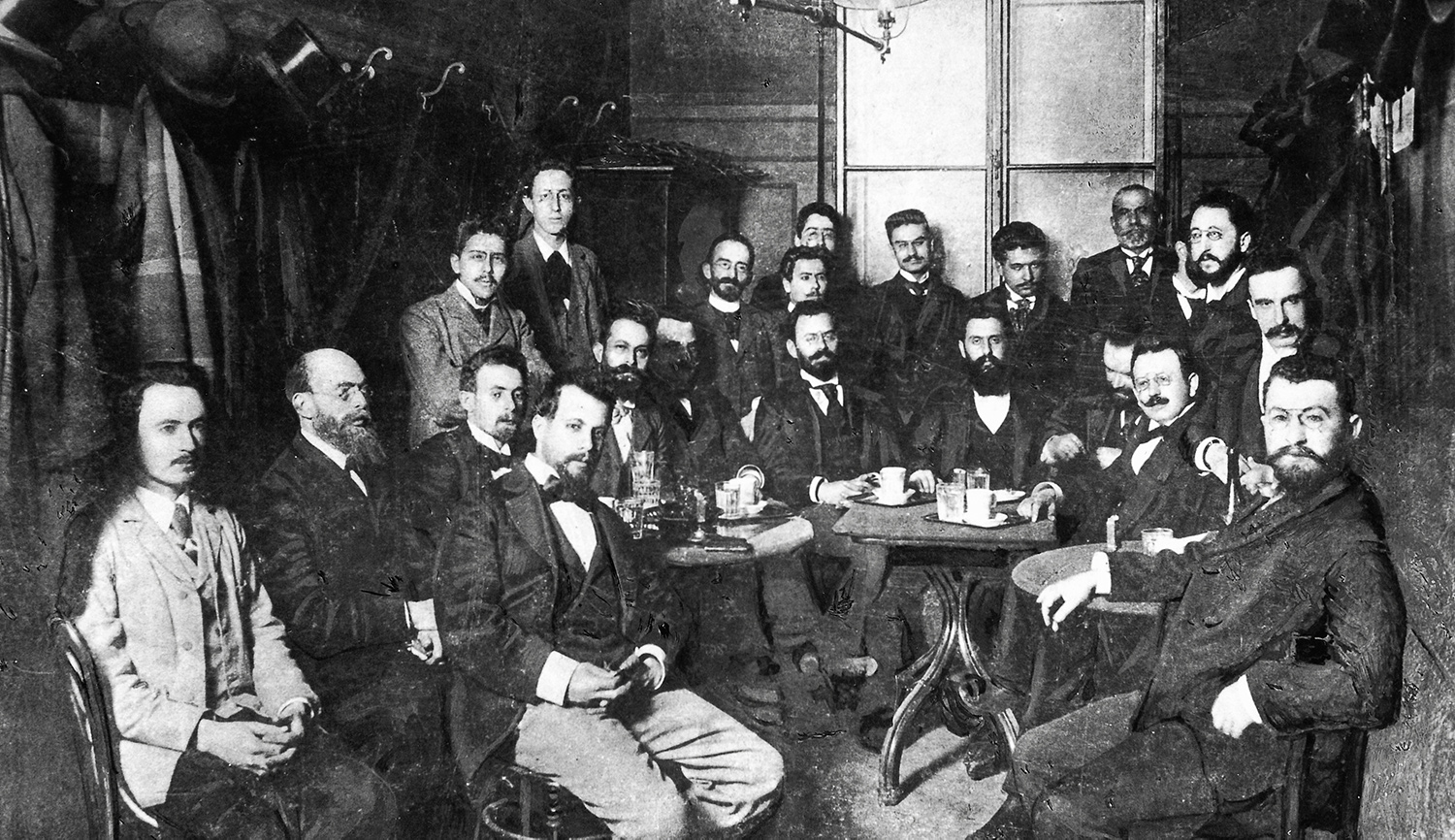

Fascinated by Richman’s contrast between these two figures, I want to explore why Herzl succeeded where Pinsker failed. What makes the comparison so interesting is the extraordinary number of similarities between them. Both were proud Jews who became prominent through their success in general rather than Jewish society. Gifted thinkers and excellent writers, they reached similar conclusions about the need to establish a Jewish state in response to surging anti-Semitism; and laid out their views in German in short books aimed at the Jews of Western Europe. Both were dismissed by contemporaries as crazy; rejected by the wealthy and powerful Western Jews whose help they sought; began by favoring a Jewish state in whatever territory was most practical and came to support the Jews’ return to Israel; and headed international movements, Ḥibbat Tsion (Love of Zion) in Pinsker’s case and the World Zionist Organization in Herzl’s.

There are of course many differences between the two men in personality, ambition, energy, and charisma, and these go a long way towards explaining the contrasting results they achieved. Inspired by the Richman essay, I reread Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation and Herzl’s The Jewish State and concluded that the most telling differences between them were actually on the level of ideas and core beliefs, as articulated in these works. I will focus on three key contrasts that explain why Herzl succeeded in igniting an international movement that gave birth to a state whereas Pinsker’s efforts netted only a small, struggling organization.

The first difference is in how they saw the Jews as a collective. For Pinsker, “The Jews are not a nation because they lack a certain distinctive national character, possessed by every other nation. . . . The Jews seem rather to have lost all remembrance of their former home.” Going further, he wrote: “Indeed, what a pitiful figure we cut! Our fatherland—the other man’s country; . . . our weapon—humility; our defense—flight; our individuality—adaptability; our future—the next day. What a miserable role for a nation which descends from the Maccabees!”

Herzl, by contrast, declared “We are a people—one people”: a simple statement that electrified his readers, Jews scattered around the world but possessed by a visceral sense they were connected to one another and part of something far greater than their home community. To Herzl, the idea of a Jewish state possessed enormous power precisely because “the Jews have dreamt this kingly dream all through the long nights of their history. ‘Next year in Jerusalem’ is our old phrase.”

When Jews read Pinsker’s book, filled as it was with brilliant insights and heartfelt pleas to take their fate into their hands by establishing their homeland, the message failed to uplift them because its author conveyed a skepticism that they had the nationalist sentiment needed to rise to the occasion. Herzl’s readers, by contrast, were inspired that he believed them to be proud members of a still-vibrant nation, and responded by fulfilling his expectations that they would rally around the flag he raised. In reading Herzl, I am reminded that Churchill inspired the British in World War II by declaring that they were and had always been lionhearted, and speaking confidently of how they would act indomitably in the face of all dangers.

Second, Pinsker argued compellingly that anti-Semitism was a permanent feature of mankind, that only the creation of their own state could improve the lot of the Jews, and that circumstances made its establishment a possibility for the first time in centuries. Yet only in the final pages of Auto-Emancipation did he lay out the barest outlines of a plan, briefly suggesting how the Jews could act collectively to secure a suitable land and to take the initial steps in settling it.

Herzl, by contrast, devoted most of The Jewish State not to laying out the “why,” but the “how.” From its first pages, he stressed that his proposal is eminently practical. and in the second chapter asserts confidently, almost matter-of-factly: “The plan, simple in design, but complicated in execution, will be carried out by two agencies: the Society of Jews and the Jewish Company. The Society of Jews will do the preparatory work in the domains of science and politics, which the Jewish Company will afterwards apply practically.” Chapter Three, on “The Jewish Company,” makes for dull reading, as its sub-sections cover nuts-and-bolts subjects, running from “non-transferable goods” and “purchase of lands” to “buildings,” “workmen’s dwellings,” “unskilled laborers,” and the like. Whether or not they found the details gripping or persuasive, his readers saw a detailed plan that appeared to have been thought through carefully, and it dawned on them that the seemingly crazy idea of establishing a Jewish state might actually work after all.

Pinsker, who sought to persuade readers that a Jewish state was necessary without demonstrating that it was possible, proved unable to inspire them with his dream. Herzl’s insight was that human beings, if not convinced that an idea is feasible, are unable to consider seriously whether it is desirable. By giving his readers a plethora of details, instead of numbing them he gave them license to be inspired by the prospect that a Jewish state could be built—and they could be its builders.

The last key difference between the two men is in the level of optimism they projected. Pinsker believed the timing to establish a Jewish state was propitious, because the impact of 18th- and 19th-century thought was that “We feel not only as Jews; we feel as men. As men, we, too, wish to live and be a nation as the others.” Likewise, “the general history of the present day seems destined to become our ally. In a few decades we have seen rising into new life nations which at an earlier time would not have dared to dream of a resurrection.” Yet despite this apparent tailwind, all he could muster in his conclusion was the alternation of exhortations with cautionary notes:

Of course, our national regeneration can only proceed slowly. We must take the first step. Our descendants must follow us at a measured and not over-precipitant speed. . . .

The financial execution of the undertaking does not present insurmountable difficulties.

Help yourselves, and God will help you!

Herzl, by contrast, expresses throughout The Jewish State a steadfast belief that the dream would be realized. Early on he notes: “I shall therefore clearly and emphatically state that I believe in the practical outcome of my scheme. . . . The Jewish state is essential to the world; it will therefore be created. The plan would, of course, seem absurd if a single individual attempted to do it; but if worked by a number of Jews in cooperation it would appear perfectly rational, and its accomplishment would present no difficulties worth mentioning.”

In his conclusion, aptly quoted by Richman at the end of his essay, Herzl’s optimism bursts through with an enthusiasm that is infectious:

Therefore I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. Let me repeat once more my opening words: the Jews who wish for a state will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.

Herzl understood that to attract men to dedicate their lives to doing the impossible, the leader sounding the clarion call had to appear absolutely convinced it would succeed.

The Maccabeans did indeed rise again and create their state because Herzl looked at the Jews and saw a vibrant nation, created a plan that made it seem that the Jewish state could really be built, and demonstrated an unwavering faith that this age-old dream would become a glorious reality.