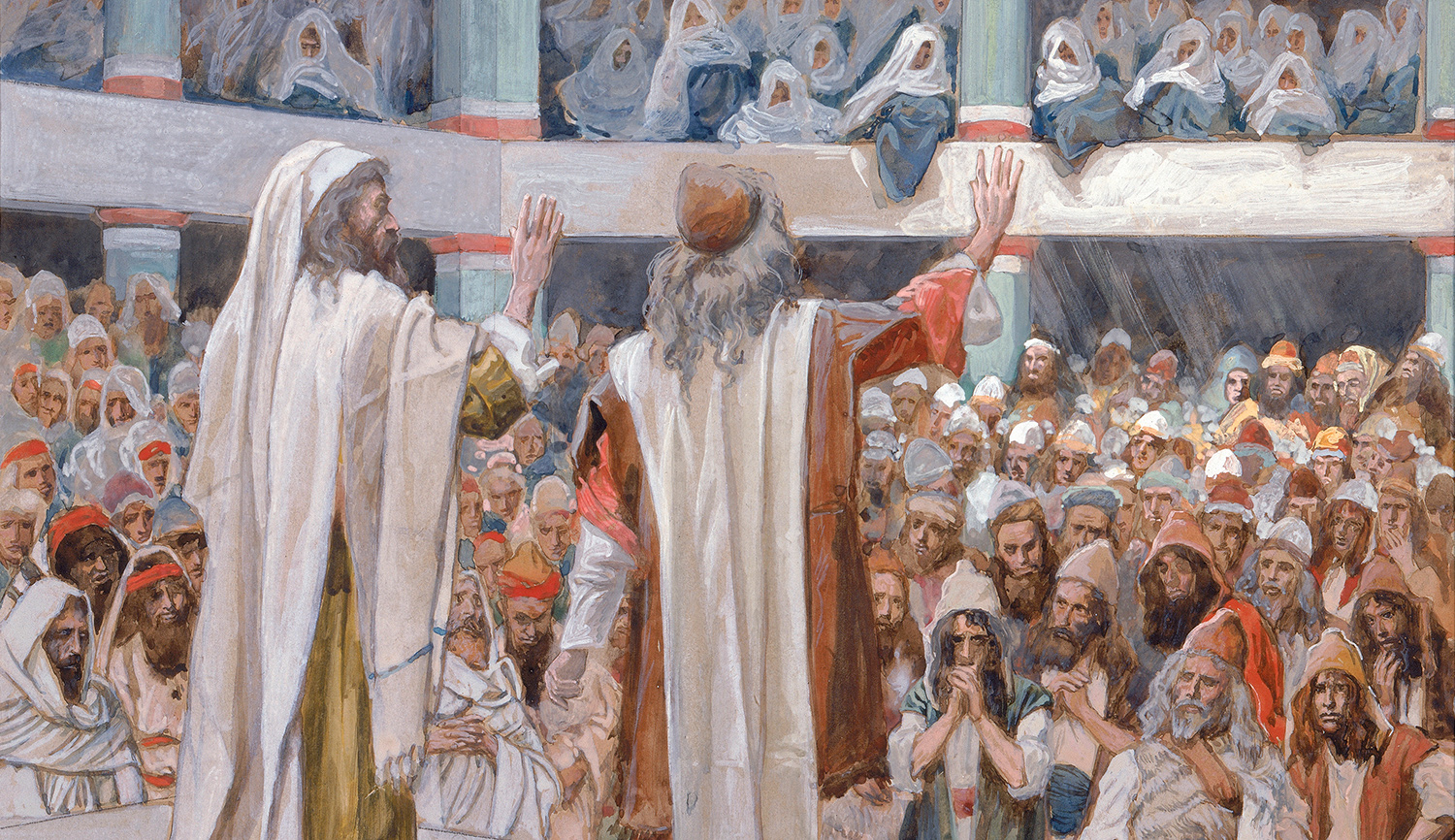

Exodus

The author of our April essay joins us to talk about how to read the book of Exodus, how the Israelites became a people, and plenty more.

He is still full of hope, and so—in replying to those who would misunderstand me and my method of reading the Bible—am I.

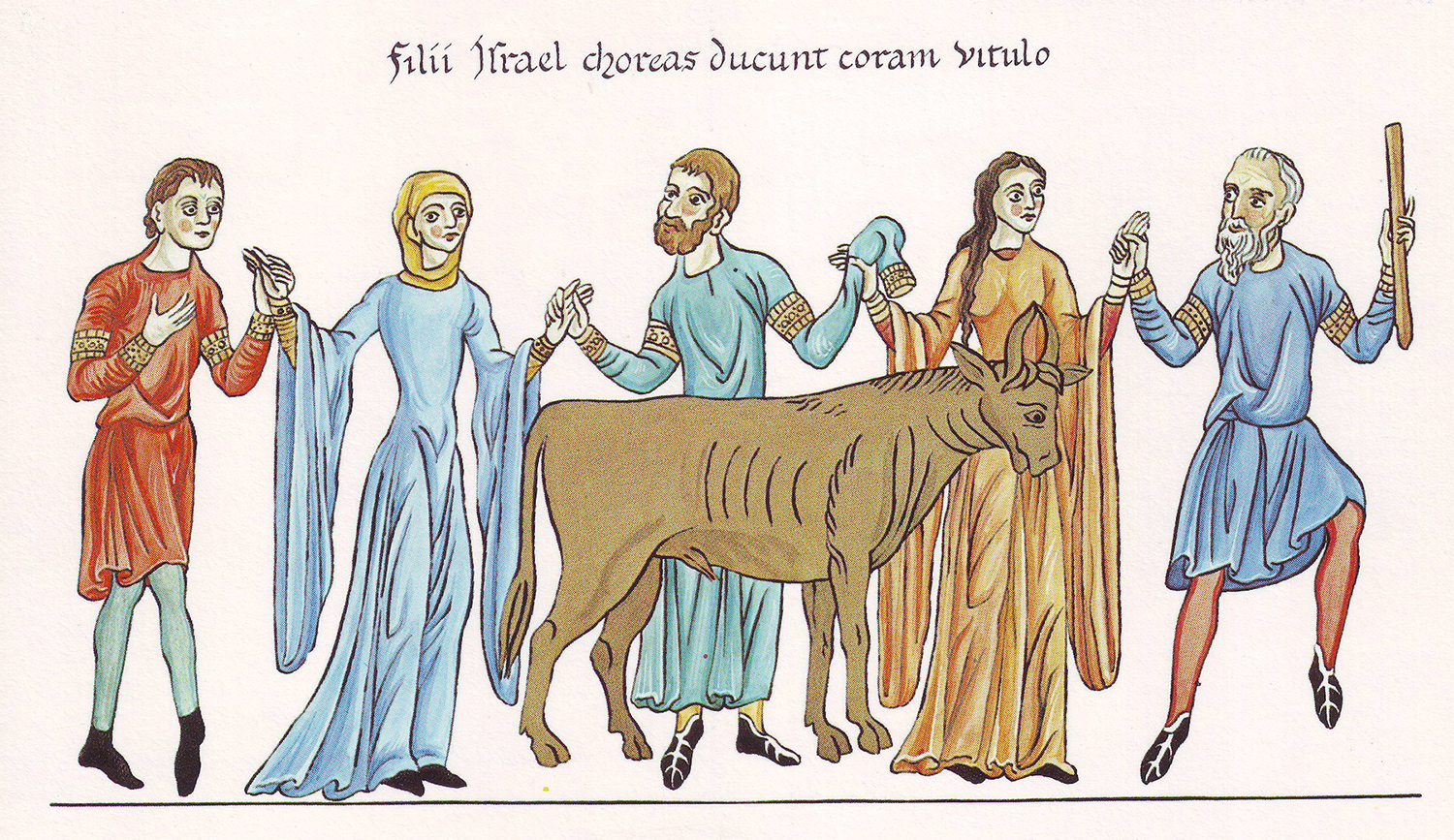

The conventional assignment of the family birthright to the firstborn comes under criticism in all of the family stories in Genesis; in Exodus, the issue becomes even more complicated.

A famous and sorely misunderstood painting of Napoleon touching plague victims in Palestine illuminates the current moment.

It’s hard to extract universal philosophical or political lessons from a set of books that is so resolutely particular.

An expression of God’s enduring compassion.

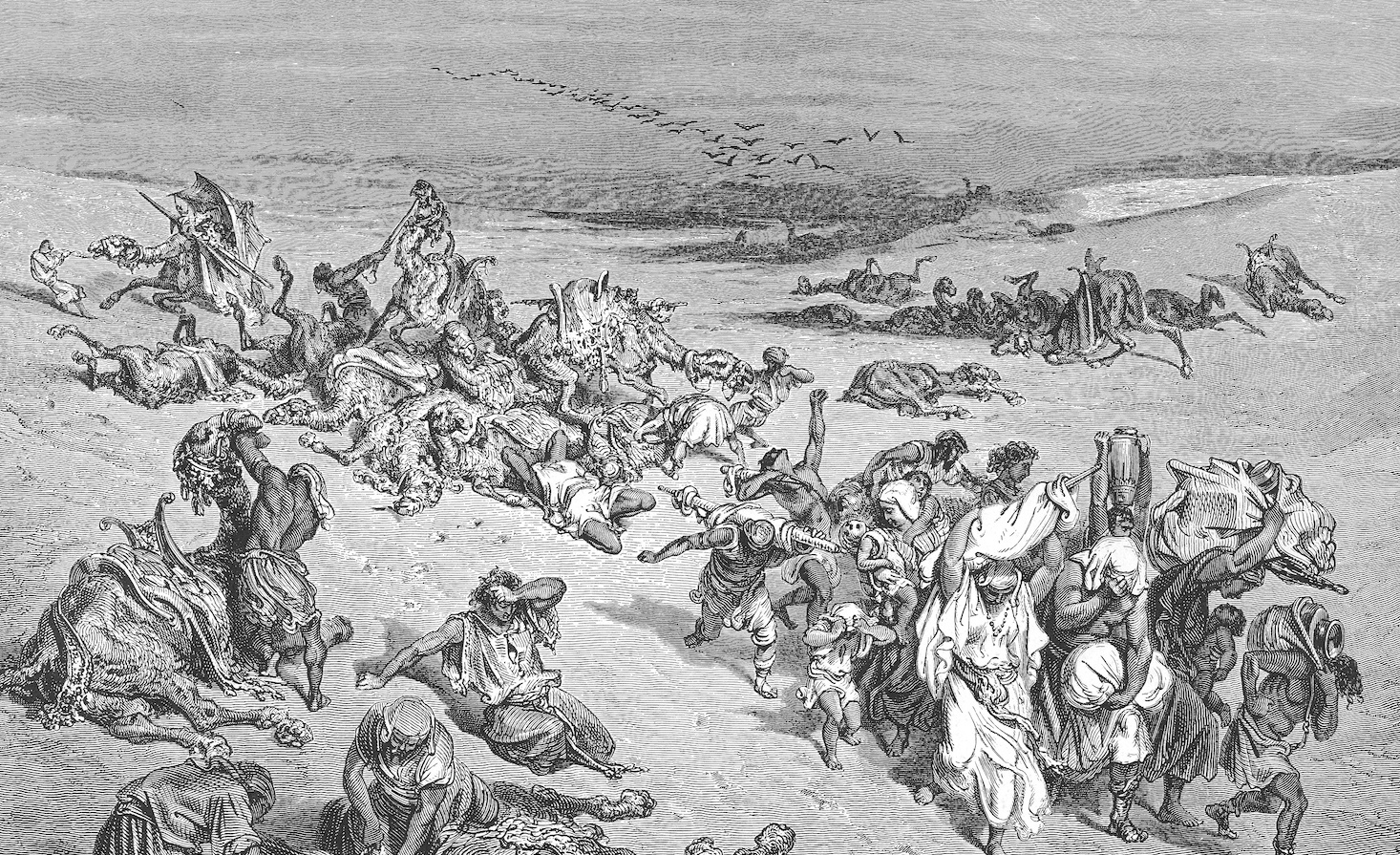

Read to its tragic depths, the Bible suggests that the last, cruelest laugh is always on God.

Satan at the seder.

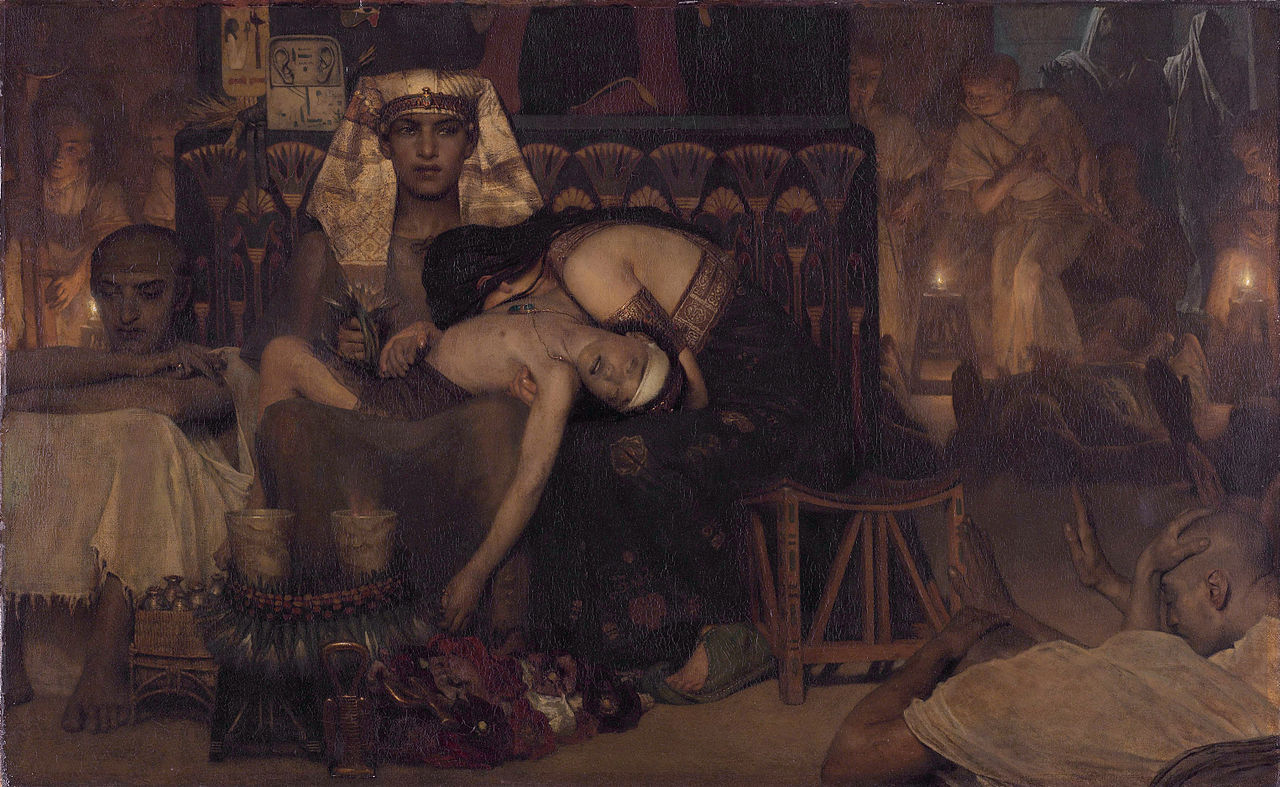

Is there a difference between pestilence and plague?

A tale of two Josephs.

There’s a great deal more at stake in Exodus than getting the slaves out of Egypt. What might it be?

“We shall do and we shall understand.”

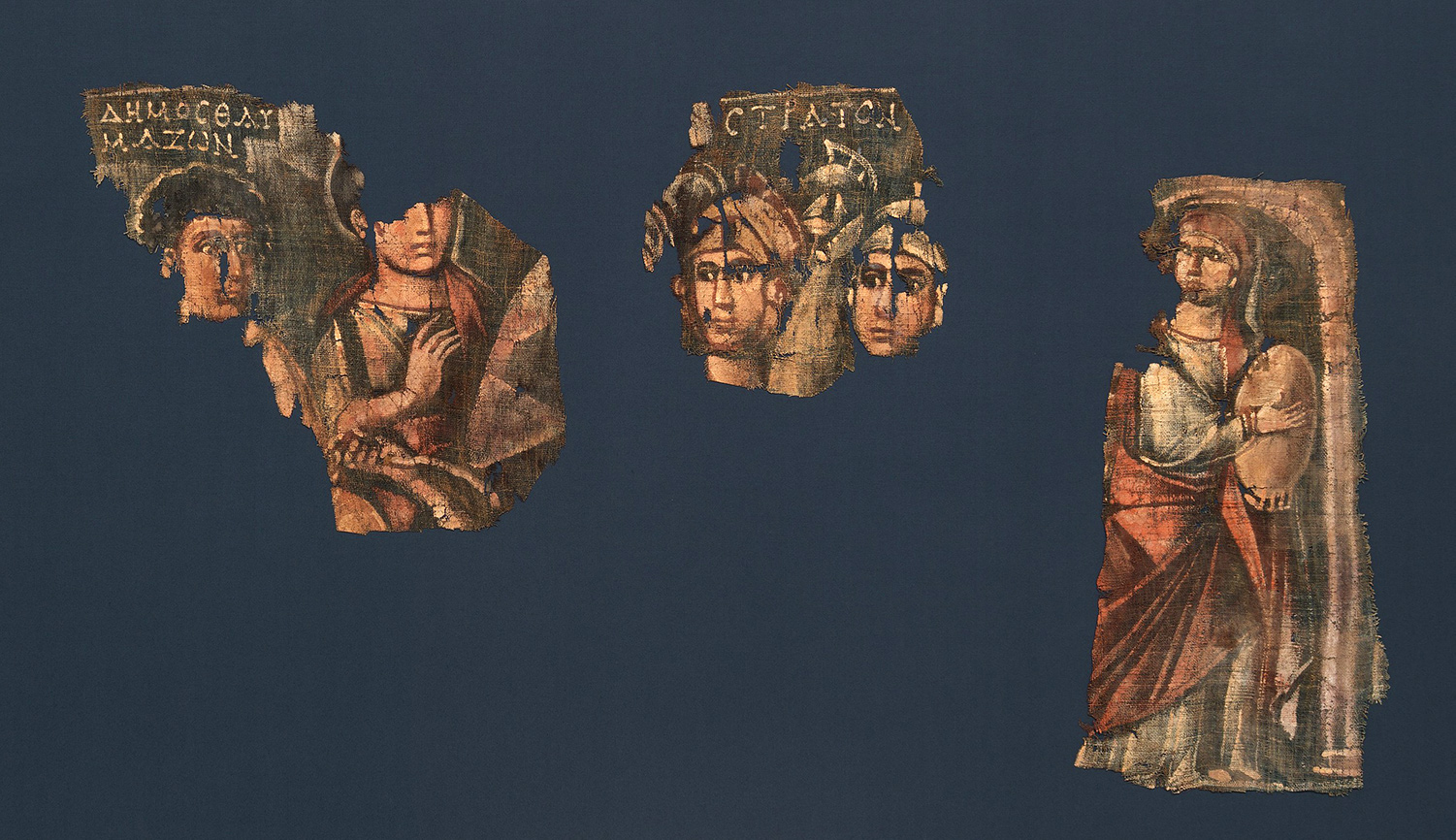

Perhaps they weren’t so multitudinous after all.

It takes a village to raise a sinner.