To mark the close of 2023, we asked several of our writers to name the best books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. The second group of their answers appears below. Part I appeared yesterday and is available here. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2023. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Hussein Aboubakr

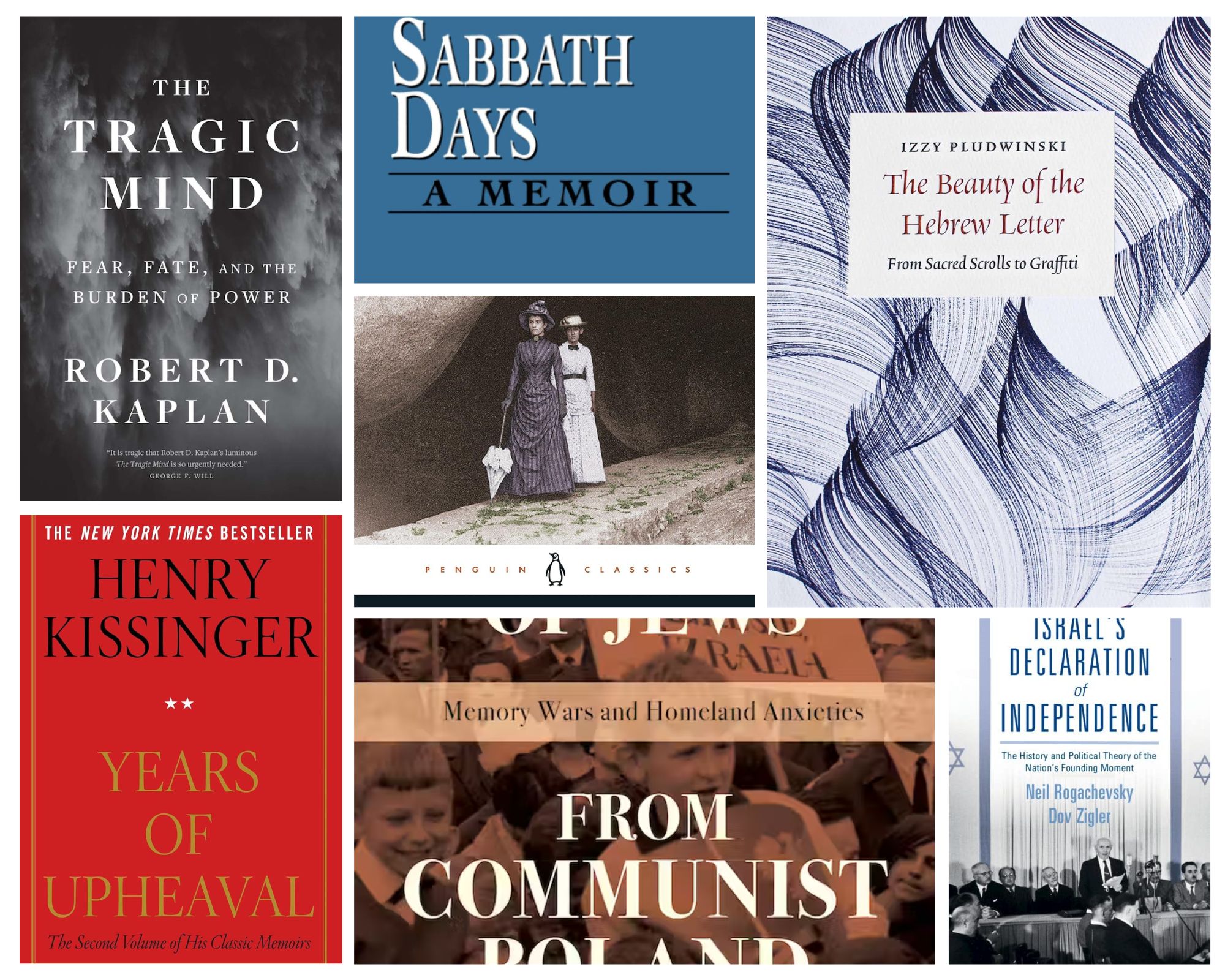

In The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of Power (Yale, 152pp., $26), Robert D. Kaplan incisively distills a lifetime of witnessing wars and revolutions into a profound lesson on the necessity of tragic thought. This concise and highly readable book serves as a testament to four decades of Kaplan’s experiences as a foreign correspondent in regions embroiled in unrelenting conflict and upheaval. The book begins with a striking declaration, “While an understanding of the world starts with maps, it ends with Shakespeare,” which encapsulates its thesis: the enduring wisdom of literary classics offers a more substantial and practical guide to comprehending our world than any contemporary social-science methodology could ever provide.

Kaplan’s narrative is not merely a critique of the current impoverished state of geopolitical discourse but an eloquent homage to the rich tapestry of historical thought. His interlacing of historical thinking and stylistic elegance illuminates a human reality obscured by the fog of modern politic science’s overspecialization and esoteric jargon. In this way it recalls the themes of Hans Morgenthau’s Scientific Man vs. Power Politics (Chicago, 1946, 255pp.), with its critique of the era’s dominant ideologies—liberalism and Communism—and their fixation on the scientific stewardship of humanity. Morgenthau, writing in an era when both philosophies were at their zenith, decried their neglect of life’s inherent tragedy, a neglect he poignantly and unironically termed “the tragedy of the scientific man.”

Kaplan’s work, in its contemplation of the tragic, serves as an apt sequel to Morgenthau’s treatise. As Morgenthau wrote concerning the base forces of human nature, and Kaplan approvingly quoted, “To improve the world one must work with those forces, not against them.”

In the literary tapestry woven by E.M. Forster in A Passage to India (Harcourt Brace, 1924), one discerns a profound resonance with the themes Kaplan explores in The Tragic Mind. Forster’s novel sensitively reveals the intricate and tragic cultural entanglement between East and West. It is a book whose insights continue to reverberate in the contemporary world.

Set amid the complex backdrop of the British Raj, the novel transcends mere storytelling to become a heart-rending exploration of the labyrinthine and often insurmountable chasms that separate two civilizations. Forster’s artful prose navigates the convoluted terrain of human relationships, scarred by the enduring shadow of imperialism. Central to the novel is the question, “But can the Indian and the Englishman really be friends?”

A Passage to India doesn’t only offer a critique of imperialism but a profound commentary on the tragic nature of the human condition, in which the failure to bridge differences spawns a sea of mistrust and political discord. Forster illustrates how the subtleties of interaction, as trivial as a smile, can have profound, unforeseen implications on the grand stage of empire, a claim of which both Morgenthau and Kaplan would approve. Much like those in Kaplan’s work, Forster’s characters find themselves ensnared in their respective cultural and historical contexts, unable to diverge from the tragic paths set before them. This novel is a timeless reflection on the enduring complexities and tragedies inherent in human relationships across the cultural divide.

Andrew Koss

In 1967 and 1968, Poland implemented a policy that had been previously carried out in England, France, Hungary, Spain, Portugal, and Austria: it drove out its Jewish population. This event was deeply tied up with the major political upheavals of those years, but is little known outside of Poland itself and the community of expellees who settled in Israel. Anat Plocker, whose mother was one of them, provides a comprehensive and thoroughly researched account of this episode in The Expulsion of the Jews from Communist Poland: Memory Wars and Homeland Anxieties (Indiana University, 2022, 240pp., $30). While I have various interpretive quibbles, they are far outweighed by the value of the story this book tells. If you believe that there are hard distinctions between rightwing and leftwing anti-Semitism, between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, or between religious anti-Judaism and political anti-Semitism, The Expulsion of the Jews will convince you otherwise.

Chaim Grade was a Jew who spent his formative years in Poland, specifically in Vilna (now Vilnius, Lithuania). He came from a poor family; attended an elite yeshiva that fostered radical introspection and encouraged emotional turmoil; left yeshiva and religious life for a career as a Yiddish poet in the mecca of Jewish literature; started and ended a romance; fell in love with and married another woman; and after surviving World War II became a great Yiddish novelist.

All this would have made excellent material for an autobiography, but Grade doesn’t use it at all. Instead, his breathtaking My Mother’s Sabbath Days: A Memoir (translated by Chana Kleinerman and Inna Hecker Grade, Jason Aaronson, 1982, 416pp., $45.99) focuses on his pious, unassuming mother while the narrator is a secondary character. Only in the book’s second half, about his wartime flight to Tajikistan, does the author take center stage. The book ends with a meditation on the Holocaust every bit as religiously sophisticated as Grade’s My Quarrel with Hirsh Rasseyner, and as searing as the most powerful liturgical elegy.

The contrast between the quiet joys and sorrows of domestic life and the high drama of psychological turmoil, political struggle, and religious doubt is one of the many themes of Gary Saul Morson’s Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter (Harvard, 512pp., $37.95). This highly readable and engaging book is a literary history like no other, taking Russian novels, stories, and plays as the great explorations of the human condition they are. Both a brief for literature itself and a window into the “Russian soul,” much of it is strikingly relevant for the questions of today.

Jonathan Silver

I’ve admired many books that came out this year, including Rick Richman’s work of political portraiture, And None Shall Make Them Afraid, Tara Isabella Burton’s newest volume of social analysis, Self-Made, and Rabbi Meir Soloveichik’s examination, in Providence and Power, of Jewish statesmanship. I want to highlight two others that also made a lasting impression.

Perhaps more than any other major religious tradition, Judaism is mediated through words. God first communicates to Abraham through intelligible speech. Moses brings down from Mount Sinai tablets inscribed with words that codify the structure of Jewish moral order. The book of Deuteronomy commands that every Jewish king write his own Torah scroll. Words adorn the vertical beam of a Jewish doorpost, are affixed on arms and foreheads in prayer, and are used to join together a bride and groom in marriage. For millions of Jews, the study of Jewish texts—including the oral Torah that records the built-up tradition of rabbinic sages mixing their intellect and creativity together with our sacred inheritance—the study of these written words constitutes the holiest activity of all.

So it is not surprising that words, letters, the technology and artistry of writing—the vocation of the scribe, the sofer in Hebrew—deserve an elevated place in our tradition. The English word calligrapher comes from the Greek for “beautiful writing,” and the vast tradition of Hebrew calligraphy offers no small amount of beautiful writing indeed, words and letters crafted to elevate and enhance the commandments of study and devotion.

The scribe Izzy Pludwinski’s The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter: From Sacred Scrolls to Graffiti (Brandeis, 240pp., $50) is a coffee-table book that is lavish with gorgeous illustrations. We see Hebrew ancient and modern, produced by reed and quill, carved into stone, hewn from wood, embossed in leather, and inscribed on the Jewish heart. By turns a work of history, graphic design, and typography, it conveys the Jewish people’s astonishing creativity and refinement in the production of the written word.

Israel, of course, turned 75 in the spring of 2023, and to mark the occasion Neil Rogachevsky and Dov Zigler published Israel’s Declaration of Independence: The History and Political Theory of the Nation’s Founding Moment (Cambridge, 300pp., $37.19), the first serious work of political science aimed at distilling the essence of Israel from its founding charter.

They are not the first scholars to do so: historians have studied Israel’s Declaration of Independence, and the Mosaic contributor Martin Kramer has written an entire series of essays on the drafting of the document. Rogachevsky and Zigler learn from this methodological approach, and they too carefully delineate the drafting process that led to David Ben-Gurion’s final version. But historical analysis is not their book’s highest objective.

By tracing the political ideas that endure from one draft to the next, and the formulations and principles that are changed or removed and replaced, Rogachevsky and Zigler aim to articulate a political theory of the Israeli founding, in which the purposes of Israeli sovereignty are made most clearly manifest. They aim in this book to do for the Israeli founding what scholars such as Herbert Storing and Martin Diamond, or Walter Berns and Harry Jaffa, attempted to do for the American founding.

Israel’s Declaration of Independence illuminates how Israel’s founders thought about rights, their origins, their purview, citizenship, and the justification for Israel’s sovereignty, and how the state instituted by this document would secure freedom and order, and safeguard its biblical birthright.

Meir Soloveichik

The two most fascinating books that I have read this year were published decades ago, yet are strikingly relevant in this very moment; one is still celebrated, while the other is entirely forgotten, but ought to be rediscovered.

The first is Henry Kissinger’s memoir Years of Upheaval (Simon & Schuster, 1982, 1,312pp., $37.50), which focuses on the last years of the Nixon presidency. The book is immensely instructive for its fascinating portrayals of political figures and reflections on the nature of statecraft itself. As Norman Podhoretz reflected in his original review of the book, whatever one’s view of détente, the book is a masterpiece of political writing. Its discussion of the Yom Kippur War, 50 years after it occurred, is of course profoundly pertinent to our moment.

The second book is by a man named Abraham Kotsuji, though that is not the name he was given at birth. Setsuzo Kotsuji was born in Kyoto in 1899, raised in the Shinto faith, and converted to Judaism at the age of sixty. His memoir, From Tokyo to Jerusalem (Random House, 1964, 215pp.), describes his heroic actions on behalf of Jews that arrived in Japan during World War II. The book is also a religious classic in its own right, a tale of a journey for Shintoism to Judaism that deserves to be republished today.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Literature, The Year in Books