Jack Wertheimer’s excellent distillation of the current condition of Modern Orthodoxy in America captures the complex and fluid nature of this group of Jews. For those who once judged Orthodoxy in the post-Holocaust world to be on a fast path to extinction, a “residual category” populated by Jews living in a past beyond retrieval, the Modern Orthodox were the exception, and the best hope for the future of American Judaism.

But so, too, it turns out, were all sorts of Orthodox Jews.

Long before the recent Pew survey, anyone who studied or lived among observant Jewry would have recognized that, rather than hopelessly fading into the past, American Orthodoxy was thriving. Ironically, the movement whose members had been warned by their European leaders not to go to America—where, the rabbis cautioned, Jews might be saved but Judaism would not—discovered that this open society, with its expanding cultural tolerance, declining anti-Semitism, physical security, rapid economic growth, and robust welfare system was actually a perfect place in which Orthodoxy could thrive and grow. Indeed, in this new social environment, Orthodoxy not only threw off those of its number who were Orthodox only in name but not in observance; it also began turning toward more punctilious and haredi forms of Orthodoxy—“sliding to the right,” in the title of my book on this phenomenon—and, in the process, experienced unprecedented growth.

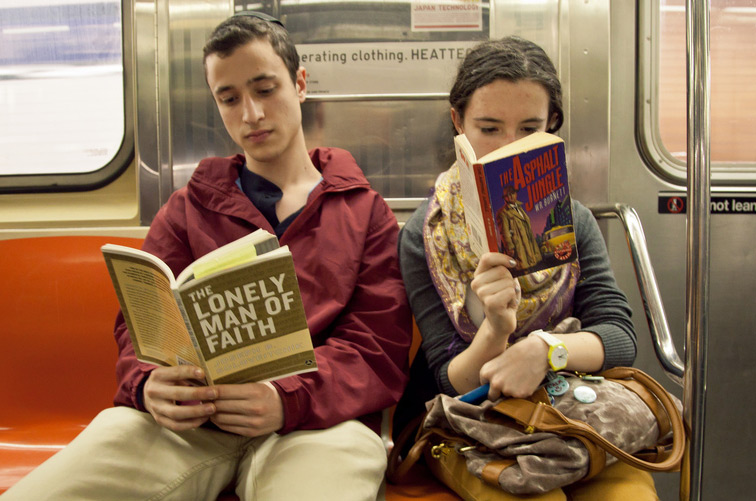

In reproducing itself, Orthodoxy evolved many cells, defined by varying behaviors and ideologies. Wertheimer has delineated some of these; others keep revealing themselves as Orthodox Jews search for ways to express their often nuanced differences. Modern Orthodox Jews combine their involvements in the contemporary world and secular culture with their contrapuntal commitments to an Orthodoxy that calls for ever more observance, more Torah study, more resistance to what are viewed as the insidious seductions of contemporary popular culture. Many Modern Orthodox Jews, especially those under thirty-five, turn to social media or Internet chat rooms to air the tensions arising from their not always harmonious choices, seeking the comfort and help of their peers in navigating between the Scylla and Charybdis of their contradictory and often double lives. All this variance is to be expected, for no expanding group can remain monolithic. As even haredi Jews are discovering, one size cannot fit all; there are many shades of black.

Within Modern Orthodoxy, one discovers sometimes exquisite feats of compartmentalization: people who are punctilious in religious observance or fervent in prayer but liberal to lax in their sexual behavior or when it comes to the laws of family purity; dedicated to regular Talmud study but captured by their careers and/or on the lookout for newer and more absorbing leisure activities; supportive of feminist goals but opposed to giving women a greater role in the synagogue or in public religious life; covering their heads in public but willing to catch the latest risqué movie or TV series. One could go on. There are even those who, though calling themselves Orthodox, are not ready to be bound by what they see as Orthodoxy’s ever rising behavioral demands and religious restrictions. As Wertheimer notes, they even have a new name: “Open Orthodox.”

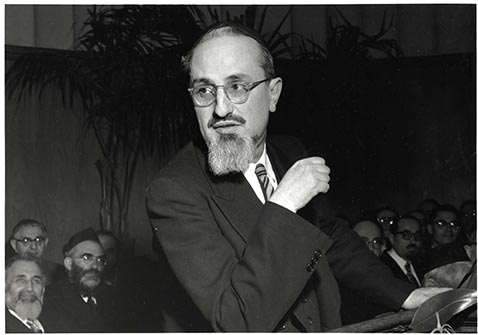

In terms of religious leadership, Modern Orthodoxy certainly lags behind its haredi counterparts. In large measure, this is because, as I have noted elsewhere, it is in the nature of modernist movements to eschew clerical authority. As moderns, moreover, Modern Orthodox Jews have increasingly relegated the field of rabbinical activity to those on their religious right; the latter, for their part, gladly assume these roles—from pulpit rabbis to educators in day schools and yeshivas, from kashrut supervisors to scribes—in the confidence that by doing so they will re-orient Orthodoxy in their direction. And some have succeeded in that aim, although they have paradoxically also stimulated a backlash in the Modern Orthodox world, hailed by some as a welcome sign of that world’s revival and rejuvenation. Among other manifestations, Wertheimer mentions Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, and the champions of partnership minyanim.

Modern Orthodoxy is not only an American phenomenon. Its longstanding Israeli counterpart bears the label dati le’umi (national religious), thereby signaling its distinctive investment in Zionism and nationalism. To many, indeed, the Israeli option is appealing precisely because it offers a chance not only to be in society as an Orthodox Jew—that is possible in America as well—but to be fully engaged in all aspects of national life and, crucially, to help direct that life in the spirit of specifically Orthodox values and ideals. This is something that life in America or elsewhere in the Diaspora, where Jews exist in overwhelmingly non-Jewish societies, can never offer. In America, Orthodox Jews who have reached the heights of government power are expected to keep their specifically Jewish behavior and ideas safely enclosed in a private compartment of their lives. Who aside from the Orthodox themselves are mindful that Jack Lew, the Secretary of the Treasury, is Orthodox?

In Israel, Modern Orthodox Jews who look like Modern Orthodox Jews can aspire to the very highest levels of power and influence in government, the military, the courts, and even the media; the kippa on the head, beard on the face, or kerchief or wig in the case of women, are not barriers to engagement or leadership in ways they would be even in multicultural America, even in New York. But in Israel these modern Orthodox can also do more. They can bring their Orthodoxy, its behavior and beliefs, to the forefront, and seek to steer the state and its institutions accordingly. In a Jewish state, Orthodoxy can and does compete to define what is Jewish and how that should be expressed in the life of state and society.

This is hardly to say that Modern Orthodoxy in Israel is without problems of its own, some of which are similarly captured in the phrase “sliding to the right.” In the Israeli context, however, the term “Right” encompasses not only stricter religious behavior and haredi values or perspectives but also an aggressive political nationalism. The latter thrust within the dati le’umi world has turned the commandment to “settle the land”—that is, the biblical land promised by God and “miraculously” returned to the Jews by events seen to be messianic in their significance—into the most important commandment of all.

This emphasis on the religious imperative of settlement above all else, and the obsessive internal argument that has arisen over it, have had a distorting effect on Modern Orthodoxy both in Israel and among those in the Diaspora who vicariously define their Orthodoxy by reference to their counterparts in the Holy Land. An Israeli Modern Orthodoxy that once found creative new ways of observing halakhic Judaism while maintaining a Jewish state—how to keep a dairy farm running, or the electrical grid functioning, without transgressing the Sabbath; how to manage an army without compromising Jewish law; how to observe the biblically mandated sabbatical year without harming agricultural productivity; how to create a banking system that does not transgress the laws of usury; how to “nationalize” Passover in a Jewish society where the level of religious observance is mixed at best; and so on—that Orthodoxy has become fixated on the issue of settlements at the expense of its own religious development and its outreach to the modern world.

The preoccupation of the dati le’umi world with the settlement issue—with seeing God’s will in territorial terms—has paradoxically contributed to enhancing, even more powerfully in Israel than in the Diaspora, the influence of the haredim, whose concern with settlement as a religious obligation is negligible. Freed from the Modern Orthodox/dati le’umi settlement fixation, haredim have been able effectively to advance their own definition of how Orthodoxy can and should engage with the contemporary world. Even in the area of outreach both to other Jews and the larger society, once the most compelling aspect of Modern Orthodoxy, the edge now goes to Lubavitcher Hasidism.

That leads me to my final point. In their tolerance of modernity (uncharacteristic of haredi Jews in general) and their ability to negotiate with it, Lubavitcher hasidim have created institutions, from Chabad Houses on university campuses and in farflung places around the world to such unabashed displays of Jewishness as the “mitzvah mobile” and the outsized Hanukkah menorah in the public square, that can attract and raise the consciousness of Jews who might otherwise have found their way to the precincts (or at least the outskirts) of Modern Orthodoxy. Most supporters and fellow travelers of Lubavitch are neither Orthodox nor hasidic, nor likely to become so. And yet Chabad, and the driven young couples who run its outposts, create a uniquely welcoming environment for these Jews: a kind of flexible Orthodoxy-lite.

Paradoxically, it is these same Chabad shluhim who also provide a safe harbor for Modern Orthodox Jews, the cosmopolitans of the Orthodox world, wherever they may find themselves: a needed minyan, a kosher meal, a place to spend Shabbat far from home, a nursery school or some other Orthodox-like institution, often for free or at cost. They do this because, in addition to the desire to spread their ideas of messianism, Lubavitchers aim ultimately to make their way the new standard of observant Judaism: Orthodox and yet at home in the modern world. This unspoken but unmistakable goal means that Lubavitchers are, for Modern Orthodox Jews, the competition that never quits.

_________________

Samuel Heilman, professor of sociology at Queens College of the City University of New York, is the author of, among other books, Cosmopolitans and Parochials: Modern Orthodox Jews in America (with Steven M. Cohen), Defenders of the Faith: Inside Ultra-Orthodox Jewry, and The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson (with Menachem Friedman).

More about: Chabad, Halacha, Jack Wertheimer, Judaism, Modern Orthodoxy